The U.S. deflation debate is over – How the U.S. avoided “Japan disease”

Rising stock prices have put an end to arguments about whether or not the United States will suffer from “Japan disease.” The euro crisis has settled down and the spread of this problem to other regions has been blocked. U.S. stock prices have reached a new post-bubble high, clearly demonstrating that the stock market is still climbing after hitting bottom in March 2009. Only six months ago, many people were convinced that the United States would become mired in Japanese-style deflation. But subsequent events have shown that this belief was mistaken. Figure 1 shows the extreme gap between U.S. and Japanese stock prices in the wake of the Lehman Brothers collapse. There were two possible explanations for this gap. First, the U.S. stock market rally was a sham (U.S. deflation would cause U.S. stocks to slump just as in Japan). Second, the Japanese stock market downturn was abnormal (the end of deflation in Japan would cause Japanese stocks to rally just as in the United States). Current events are showing us that the first explanation was the wrong one.

The Fed’s creative monetary policies made a decisive contribution to this process. If the Fed had relied on monetary policies based on tradition and textbooks, there is no doubt that the United States would have experienced another Great Depression. Furthermore, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said that it is far too early to declare victory because unemployment is still too high and an economic recovery cannot yet be confirmed. As a result, the chairman has made it clear that all options for additional measures to boost economic growth are on the table, including more quantitative easing. “The recent news has been good. But I think we need to be cautious and make sure this is sustainable. We haven’t quite yet got to the point where we can be completely confident that we’re on a track to full recovery,” he stated.

The BOJ should learn a lesson from the effectiveness of the Fed’s creative financial initiatives (QE). However, the BOJ is hesitating. At its policymaking meeting on April 9 and 10, the BOJ decided not to enact additional quantitative easing. The resulting doubts among overseas investors about the BOJ’s stance brought an end to the decline in the yen’s value. A return to a stronger yen and deflation in Japan would cause Japan’s real interest rates to remain high in contrast to negative real interest rates in the United States and Germany. This situation would almost certainly cause the yen to become even stronger (Figures 2 and 3). Japan must use extensive monetary easing as the central element of initiatives to fight deflation in order to ensure the continuation of the yen’s downturn and stock market’s upturn that started early in 2012.

Figure 1: Equity indices in major countries (2009/3/1=100)

Figure 2: Exchange Rate of Major Currencies vs. Yen (2007/1/31=100)

The BOJ needs to closely study the Fed’s actions

At its policy meeting on April 9 and 10, the BOJ decided not to implement additional monetary easing measures. In late March, BOJ Governor Masaaki Shirakawa visited Washington and pointed out the obstacles to the long-term use of monetary easing (explaining the need to be vigilant about higher commodity prices and other side-effects of monetary easing while also noting the need for aggressive monetary easing after the bursting of the asset bubble). These actions taken by the BOJ, which could also be interpreted as a negative stance about terminating deflation, resulted in considerable distrust in financial markets. Currently, investors’ excessive aversion to risk has produced a negative asset bubble. However, the BOJ’s actions based on the fear of a positive asset bubble are certain to spark fierce criticism.

Kiyohiko Nishimura, deputy governor of the BOJ, stated that “this is an era for creating new financial theories and taking new actions that are not in economics textbooks” (Asahi Shimbun, March 23). This statement indicates that the BOJ is willing to enact creative and futuristic financial policies just as in the United States. Apparently, there is growing sentiment within the BOJ that the bank should learn a lesson from the success of the United States.

There is one key aspect above all of the Fed’s creative financial policies and quantitative easing that the BOJ should study: supplying adequate liquidity for today’s age of securitized financial markets. Since securitization is now the main source of funds, capital markets are the primary means of creating credit. Consequently, actions focused solely on increasing bank loans, which are indirect financing, will produce only limited benefits.

Increasing liquidity in direct financing markets causes the risk premium to drop, which equates to higher prices of financial assets. During the recent financial crisis, Mr. Bernanke stated repeatedly that lowering the risk premium is one of highest priority of monetary policy. This position reflects his fear of the paralysis of financial markets when panic causes people to no longer accept suitable levels of exposure to risk. Converting all capital to cash when the actions of people are ruled by panic is the ultimate form of self-denial of capital.

Figure 3: Real interest rates in major countries

Figure 4: Bank of Japan total assets

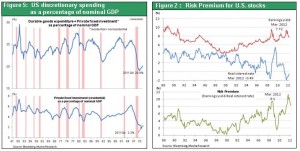

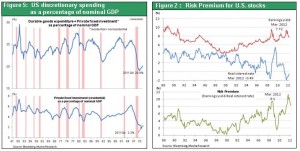

Stimulating the animal spirits of investors is vital to this process. Simply put, animal spirits involve making people more willing to take on long-term commitments. When people’s actions are controlled by an extreme sense of insecurity, they buy things to meet only their immediate needs. Once their confidence returns, they start shifting purchases to items that involve longer commitments. Consumers advance from food to clothing, home appliances, automobiles, furniture and houses. There is also a shift from home rentals to ownership. Companies switch to longer commitments, too. Instead of making only minimal maintenance expenditures, companies start spending to raise output, enter new markets and buy durable assets. As people and companies spend their money from longer perspectives, the depth of demand grows. At one point, an extreme short-term focus in the United States caused demand to become extremely thin. Animal spirits had been destroyed. An increasing commitment to long-term prosperity is the main component of animal spirits, not an increasing willingness to speculate. Consequently, animal spirits equate to stimulating interest in making long-term investments in stocks. Figures 5 and 6 show indicators that illustrate the benefits of animal spirits in the U.S. real economy and financial markets. As you can see, both indicators are still at extremely low levels.

These points also demonstrate the significance of quantitative easing. Mr. Bernanke said that the goal of QE2 was to create expectations of higher stock prices. Making people more willing to gamble with stocks was not the objective. QE2 was intended to encourage people to take on longer-term commitments. From this standpoint, QE2 was successful by producing a sufficient amount of benefits. If the benefits are still inadequate, the Fed will naturally start QE3. Quantitative easing will continue for as long as needed to keep pushing stocks up and achieve a sustained economic recovery. With inflation under control and U.S. long-term interest rates held down, the ceiling for quantitative easing is very high.

Figure 5: US discretionary spending as a percentage of nominal GDP

Figure 6: Risk Premium for U.S. stocks

The BOJ is fully responsible for the source of the “Japan disease” – extreme aversion to risk-taking

A strong yen coupled with deflation is the source of all of Japan’s problems. Deflation punishes borrowers and risk takers while killing the spirit of capitalism and animal spirits. Furthermore, deflation makes it impossible to use inflation to offset differences in productivity growth rates. The results are low productivity, stagnant internal demand sectors and a decline in wages. In other words, income distribution is distorted and income gaps widen. Another problem is growing unfairness caused by a relative increase in wages outside the business sector. The reason is that incomes of government employees and people receiving pensions do not decline with deflation as in the private sector. Ending the negative cycle of a stronger yen and deflation that characterized Japan’s lost 20 years is very likely to fundamentally alter Japan’s economy and markets. With Japan’s fiscal policy now in a state of paralysis, the BOJ alone is capable of enacting the macroeconomic measures that the country needs.

The BOJ must make a weaker yen and a lower risk premium its highest priorities.

Stimulating the animal spirits of investors is vital to this process. Simply put, animal spirits involve making people more willing to take on long-term commitments. When people’s actions are controlled by an extreme sense of insecurity, they buy things to meet only their immediate needs. Once their confidence returns, they start shifting purchases to items that involve longer commitments. Consumers advance from food to clothing, home appliances, automobiles, furniture and houses. There is also a shift from home rentals to ownership. Companies switch to longer commitments, too. Instead of making only minimal maintenance expenditures, companies start spending to raise output, enter new markets and buy durable assets. As people and companies spend their money from longer perspectives, the depth of demand grows. At one point, an extreme short-term focus in the United States caused demand to become extremely thin. Animal spirits had been destroyed. An increasing commitment to long-term prosperity is the main component of animal spirits, not an increasing willingness to speculate. Consequently, animal spirits equate to stimulating interest in making long-term investments in stocks. Figures 5 and 6 show indicators that illustrate the benefits of animal spirits in the U.S. real economy and financial markets. As you can see, both indicators are still at extremely low levels.

These points also demonstrate the significance of quantitative easing. Mr. Bernanke said that the goal of QE2 was to create expectations of higher stock prices. Making people more willing to gamble with stocks was not the objective. QE2 was intended to encourage people to take on longer-term commitments. From this standpoint, QE2 was successful by producing a sufficient amount of benefits. If the benefits are still inadequate, the Fed will naturally start QE3. Quantitative easing will continue for as long as needed to keep pushing stocks up and achieve a sustained economic recovery. With inflation under control and U.S. long-term interest rates held down, the ceiling for quantitative easing is very high.

Figure 5: US discretionary spending as a percentage of nominal GDP

Figure 6: Risk Premium for U.S. stocks

Stimulating the animal spirits of investors is vital to this process. Simply put, animal spirits involve making people more willing to take on long-term commitments. When people’s actions are controlled by an extreme sense of insecurity, they buy things to meet only their immediate needs. Once their confidence returns, they start shifting purchases to items that involve longer commitments. Consumers advance from food to clothing, home appliances, automobiles, furniture and houses. There is also a shift from home rentals to ownership. Companies switch to longer commitments, too. Instead of making only minimal maintenance expenditures, companies start spending to raise output, enter new markets and buy durable assets. As people and companies spend their money from longer perspectives, the depth of demand grows. At one point, an extreme short-term focus in the United States caused demand to become extremely thin. Animal spirits had been destroyed. An increasing commitment to long-term prosperity is the main component of animal spirits, not an increasing willingness to speculate. Consequently, animal spirits equate to stimulating interest in making long-term investments in stocks. Figures 5 and 6 show indicators that illustrate the benefits of animal spirits in the U.S. real economy and financial markets. As you can see, both indicators are still at extremely low levels.

These points also demonstrate the significance of quantitative easing. Mr. Bernanke said that the goal of QE2 was to create expectations of higher stock prices. Making people more willing to gamble with stocks was not the objective. QE2 was intended to encourage people to take on longer-term commitments. From this standpoint, QE2 was successful by producing a sufficient amount of benefits. If the benefits are still inadequate, the Fed will naturally start QE3. Quantitative easing will continue for as long as needed to keep pushing stocks up and achieve a sustained economic recovery. With inflation under control and U.S. long-term interest rates held down, the ceiling for quantitative easing is very high.

Figure 5: US discretionary spending as a percentage of nominal GDP

Figure 6: Risk Premium for U.S. stocks