May 11, 2010

Strategy Bulletin Vol.14

The Black Swan Farce

– Risk-taking will stage a quick comeback –

People were stunned at the first-ever sighting of a black swan. But this bird was nothing more than an ugly swan the second time around. Convinced that another catastrophe like the subprime loan crisis is imminent, pessimists have been steadily shorting the bonds of Greece and other European countries. But these pessimists will probably incur big losses. Now that sovereign risk is under control, we should see a big resurgence in risk-taking.

Long and short positions are the essence of finance

The farcical belief in the sovereign crisis scenario is linked to the inability of people to comprehend the true nature of finance. Essentially, finance is the use of contracts to transfer purchasing power. This is why finance has always been a zero-sum game. Now that finance has advanced to the age of securitization, changes in asset prices can immediately produce massive transfers of capital (purchasing power). In other words, whenever something is sold, something else is bought.

Of course, it is possible for a burgeoning deficit to trigger a sell-off of government bonds (producing higher interest rates) that causes a country to become insolvent. But there are only two options for using the proceeds from these sales. First is to buy physical assets, stock, debt instruments and other items that have even greater risk. Second is to hold the proceeds as cash. Holding cash (selecting the ultimate in liquidity) is an option that people choose solely during a financial panic. Obviously, people will never stay with this choice very long. The conclusion is that sellers of national government bonds will buy higher-risk physical assets and financial instruments. However, this buying will occur only when investors are expecting either a powerful economic recovery or inflation. For proof, we need look no farther than Japan, which has a budget deficit of unprecedented magnitude. But interest rates are extremely low because investors are buying Japanese government bonds in an environment of deflation and economic stagnation.

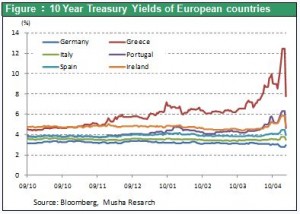

Proceeds from sales of Greek government bonds have flowed to the bonds of Germany and United States, pushing down long-term interest rates in these two countries. This represents a rapid outflow of purchasing power from Greece to Germany and the United States. Furthermore, inflows of purchasing power, which equate to lower interest rates, have become the source of funds for the immense EU stabilization fund and enabled the European Central Bank (ECB) to buy Greek government bonds. With these funds, the ECB can easily pick up these bonds on the open market at less than half their face value. So this may be an opportunity to earn a profit. In fact, the Federal Reserve Bank made a profit on mortgage-backed securities purchased during the subprime loan crisis after prices of these securities rebounded. This explains why it was possible to establish a stabilization fund of 440 billion euros.

Having reached this point, the question now is where all the money that has flowed back to the bonds of Germany, the United States and other major countries will go next. While pushing down long-term interest rates in Germany, the United States, Japan and other major global economies, inflows of capital could also have the welcome effect of increasing domestic demand in these countries. As this domestic demand grows, the liquidity crisis will disappear and we will see an even stronger recovery of the global economy. The bottom line is that ending the crisis in Greece is very likely to fuel even more risk-taking in Germany, the United States, and other industrialized nations.