The Greek debt crisis has become a European liquidity crisis

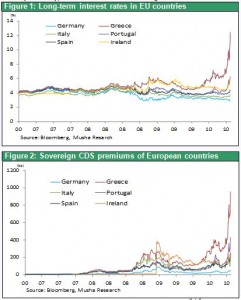

The scope of the debt crisis in Greece has expanded to become a worldwide drop in stock prices. Some people are worried about another nightmare like the one that followed the Lehman shock. In fact, there are many similarities between this crisis and the Lehman shock. We are witnessing a chain reaction of panic as selling fuels even more selling. Moreover, a plunge in the value of a relatively small volume of troubled assets (Greek government bonds this time, subprime loans in the previous crisis) may again spread to other similar asset categories (the government bonds of other small EU countries). We are also seeing a situation where credit default swaps (CDS) have become a speculative tool where selling triggers even more selling. One more similarity with the Lehman shock is that credit rating reductions that followed the outbreak of this crisis have made the problem even worse. People are starting to talk about the possibility of an increase in counterparty risk. This could occur if losses incurred by financial institutions due to their holdings of Greek government bonds cause capital shortfalls. Other banks may no longer do business with these institutions as a result.

Similarities between the Greek debt crisis and subprime loan crisis

Market values of assets have fallen far below their intrinsic values, just as we saw during the subprime loan crisis. This could be seen as a case of mispricing. The cut by Standard & Poor’s in the credit rating of Greek government bonds to BB+ means that bondholders have only a 30% to 50% chance of receiving their interest and principal. But this rating cut is in some respects an overreaction to this crisis. Once fears subside and Greece’s sovereign risk premium returns to normal, there will be a big improvement in the country’s financial situation. But the plunge in prices of Greek government bonds has created unrealized losses for financial institutions and investors. In response, banks are starting to become even more reluctant to extend credit as they seek to avoid risk. As a result, even though the crisis in Greece itself should have been a relatively minor problem, panic may cause this crisis to have a severe impact on the real economy. Furthermore, just as during the subprime loan crisis, there is mounting criticism of credit rating agencies (by the heads of European governments and the U.S. treasury secretary) because of their role in making the crisis even worse.

The parties that will deal with the Greek debt crisis have finally emerged. The IMF and EU will provide Greece with a loan of 110 billion euros. With these funds, there are no worries about redemptions of Greek government bonds in 2010. In return, Greece has agreed to a three-year restructuring program totaling 30 billion euros. Major components include hiking the value-added tax rate, cutting and freezing public-sector wages, and reducing pensions. However, the sharp increase in interest rates on Greek government bonds makes it virtually impossible to determine a method to fund repayments on Greek debt in 2011 and afterward. However, it may be easier to reschedule Greece’s debt repayments now that market prices of Greek government bonds have dropped so far.

Ending the liquidity problem will not be difficult

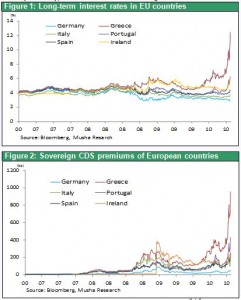

Financial markets have already turned their attention from Greece to other eurozone countries: Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Italy. A liquidity crisis is beginning to emerge as speculative selling of the government bonds of these countries grows. At this point, government intervention is the only way to terminate the spread of this crisis. There is no longer a dividing line between the monetary policy and phisical policy. Governments must monetize the debt by using their central banks to inject the public-sector funds needed to stabilize the financial system. If the crisis cannot be quelled, the European Central Bank will have to make exceptional purchases of Greek government bonds (or extend loans to Greece that are secured by these bonds) with the aims of supplying liquidity and propping up prices of assets. Supplying liquidity through purchases of Greek government bonds, which no longer have an investment-grade credit rating, would probably temporarily halt the spread of the crisis. Unlike the subprime loan crisis, there is no doubt this time about the location of the risk. Once everyone reaches a consensus that a crisis exists, it should be relatively easy for government authorities to take the necessary actions.

Fundamental contradictions of the EU ? (1) Fiscal policy leadership

A closer look at this problem reveals that the true cause is the incomplete unification of the EU, which is a fundamental contradiction. First of all, the EU has unified its finances but individual countries still control their respective fiscal policies. Under a managed currency system, the primary role of central banks is to assume responsibility for public-sector debt (which means distributing this debt in the form of currency). But this link has been severed in the EU countries. Without this link, countries are more likely to default on their bonds. Moreover, the long-term interest rates of most EU countries were about the same prior to the 2008 financial crisis. Similar interest rates throughout Europe enabled Greece and other smaller EU countries to issue bonds with little discipline. Centralizing the power to determine fiscal policies is the only way to eliminate this contradiction.

Fundamental contradictions of the EU? (2) Uneven improvements in productivity, the opportunity for growth in Germany

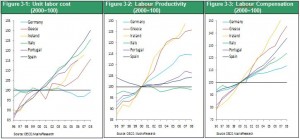

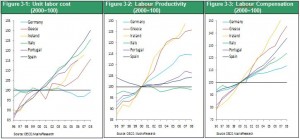

The second contradiction is rooted in the widening gap between the competitive position of each EU country. Differences in competitiveness are equivalent to differences in unit labor cost. In the EU, wages have not been determined in a manner that properly reflects differences in the rate at which productivity improves. Before currency unification, the economies of individual countries remained stable because differences in productivity and costs were offset by changes in exchange rates. But this is no longer possible. The weaker eurozone countries in terms of cost have found it extremely difficult to enact policies as a result. The first victim of the unified currency is Greece, which is the weakest of all eurozone countries.

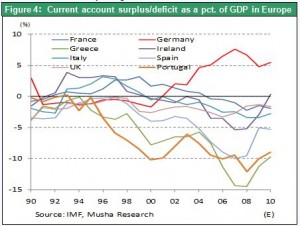

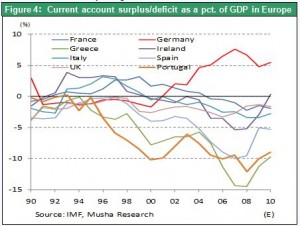

Following currency unification and the birth of the euro in 1999, Germany lost jobs to Ireland, Spain and new EU members, mainly in eastern Europe, because of its high wages. As jobs migrated to other countries, Germany was subjected to powerful deflationary forces. There was rising pressure in Germany to boost productivity while holding down wages. In the new EU members, on the other hand, wages started to climb because of a labor shortage fueled by the unification boom. Costs increased rapidly. The higher cost of doing business in these countries made Germany’s exports more competitive. Soon, Germany had a huge current account surplus while other countries had consistently large deficits. Furthermore, the fixed exchange rate system within the EU made Germany even more competitive year after year. Resolving this disparity within the framework of a unified currency requires (1) raising productivity in the EU’s emerging economies, (2) lowering wages and allowing deflation in these emerging economies, or (3) raising wages and allowing inflation in Germany. If none of these steps is possible, the only other option is (4) termination of the unified currency system in Europe.

The only viable choice now is (1) to raise productivity in the EU’s emerging economies while enacting emergency stopgap measures. Option (4) is a possibility if there is a deep downturn in the global economy. But letting the euro die is not the option from a political standpoint. For these reasons, I believe that we may see wages and corporate profit margins climb in Germany.

Numerous containment forces should resolve this crisis quickly

Currently, the primary concern is whether or not the Greek crisis will spread to other EU countries and eventually force the EU to enact radical reforms. For instance, there could be a decision to end the fiscal policy autonomy of individual countries or even to terminate the EU. But these events are unlikely to happen. I believe that it will be possible to cap the Greek crisis before it spreads because of the existence of many sources of containment: (1) cooperation will continue due to the crisis mentality of the entire world, including the IMF, EU countries, United States and others; (2) there is a strong willingness to take on risk worldwide as illustrated by the recovery of the U.S. economy and stock markets; (3) growth opportunities in the United States, Germany and other major countries are increasing as their long-term interest rates decline; and (4) further monetary easing by the European Central Bank along with the decline in the euro’s value will increase the economic growth rate of Germany, the EU’s core country, by making this country more competitive outside the EU. The surge in the crisis mentality sparked by the worldwide plunge in stock prices further underscores the likelihood of a quick resolution of this problem. Ultimately, I expect this crisis to make the economic clout of the United States and Germany even greater.

The parties that will deal with the Greek debt crisis have finally emerged. The IMF and EU will provide Greece with a loan of 110 billion euros. With these funds, there are no worries about redemptions of Greek government bonds in 2010. In return, Greece has agreed to a three-year restructuring program totaling 30 billion euros. Major components include hiking the value-added tax rate, cutting and freezing public-sector wages, and reducing pensions. However, the sharp increase in interest rates on Greek government bonds makes it virtually impossible to determine a method to fund repayments on Greek debt in 2011 and afterward. However, it may be easier to reschedule Greece’s debt repayments now that market prices of Greek government bonds have dropped so far.

The parties that will deal with the Greek debt crisis have finally emerged. The IMF and EU will provide Greece with a loan of 110 billion euros. With these funds, there are no worries about redemptions of Greek government bonds in 2010. In return, Greece has agreed to a three-year restructuring program totaling 30 billion euros. Major components include hiking the value-added tax rate, cutting and freezing public-sector wages, and reducing pensions. However, the sharp increase in interest rates on Greek government bonds makes it virtually impossible to determine a method to fund repayments on Greek debt in 2011 and afterward. However, it may be easier to reschedule Greece’s debt repayments now that market prices of Greek government bonds have dropped so far.

The only viable choice now is (1) to raise productivity in the EU’s emerging economies while enacting emergency stopgap measures. Option (4) is a possibility if there is a deep downturn in the global economy. But letting the euro die is not the option from a political standpoint. For these reasons, I believe that we may see wages and corporate profit margins climb in Germany.

The only viable choice now is (1) to raise productivity in the EU’s emerging economies while enacting emergency stopgap measures. Option (4) is a possibility if there is a deep downturn in the global economy. But letting the euro die is not the option from a political standpoint. For these reasons, I believe that we may see wages and corporate profit margins climb in Germany.