(1) German Chancellor Angela Merkel won the election but Germany is moving to the left (a pro-euro stance of fiscal expansion and support for southern Europe)

The September 22 election in Germany is over and the Merkel administration will remain in power. The loss of seats by the Free Democratic Party (FDP) raises the likelihood of a major coalition consisting of the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). A shift from the FDP, the previous coalition partner, to the SPD raises the possibility that Germany will adopt the SPD position of increasing euro support with aggressive and expansionary fiscal measures. Taking these actions will probably have an extremely positive effect on the euro by boosting Germany economic growth rate and strengthening support for southern European countries.

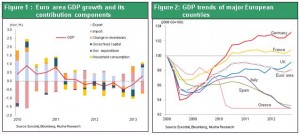

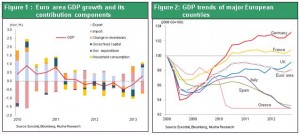

Eurozone GDP grew by 0.3% in the second quarter of 2013. This was the first growth in seven quarters and points to the end of the longest European recession in the postwar era. If Germany adopts pro-growth policies, a fairly powerful economic recovery in the eurozone is increasingly likely to occur in 2014 and 2015, resulting in economic growth in the 1.5% to 2.0% range. Furthermore, we may also see faster growth in southern European countries. The reasons are an improvement in imbalances, falling interest rates and mounting pent-up demand, as I will explain later. Along with the US and Japan, the eurozone is therefore poised to become one of the driving forces of a global economic recovery backed by developed countries. As a result, the euro crisis has probably come to an end for the time being.

Figure 1: Euro area GDP growth and its contribution components

Figure 2: GDP trends of major European countries

(2) Improvements are emerging for imbalances in Europe

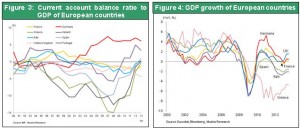

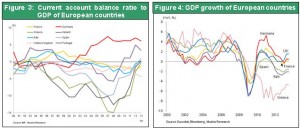

A market improvement in Europe’s imbalances took place amid the turmoil that began in 2010. Southern European countries suffered sharp economic downturns and there was a big decline in the large external current account deficits in these countries. Prior to the “Greece shock,” current account deficits were more than 10% of GDP in Greece, Portugal, Spain and other southern European countries. But these deficits have rapidly narrowed to the point where these companies are expected to break-even in 2013 or even post a surplus.

Figure 3: Current account balance ratio to GDP of European countries

Figure 4: GDP growth of European countries

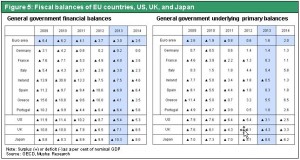

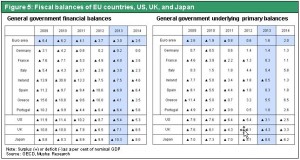

At the same time, there has been a major improvement in the financial soundness of governments because of extreme austerity measures. According to OECD statistics, the primary balance for government budgets (as a percentage of nominal GDP) became positive in the eurozone in 2012 and is expected to be 1.6% in 2013. In comparison, the primary balance in 2013 is expected to be -3.1% in the US, -4.3% in the UK and -8.5% in Japan. The eurozone’s performance is clearly outstanding. In previous years, surplus savings in Europe tended to flow from the north to the south in the form of financing. This created a cycle for capital in Europe as a whole. But now the demand for this financing has dropped significantly. Due to this change, long-term interest rates in southern European countries are much lower and financial markets are stabilizing. In Greece, the long-term interest rate peaked at 36% but is now below 10%. Long-term interest rates have also returned to generally pre-crisis levels in Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy. Big declines in budget deficits along with lower long-term interest rates are greatly reducing interest payments by the governments of these countries.

Figure 5: Fiscal balances of EU countries, US, UK, and Japan

(3) Policies in Europe are shifting centrifugal to centripetal forces

The changes I have just outlined were the result of a major shift in government policies. When the euro crisis started in 2010, a momentous change began to take place in both Germany and the southern European countries. The centrifugal forces of disintegration that were decisively growing stronger at the time changed into centripetal forces. Southern European countries (the so-called “PIIGS”) had enjoyed a “live-for-the-moment” existence until 2009 because of the euro premium (low real interest rates, and high credit standing as a member of the eurozone) and the use of markets within Europe. But once the crisis started, these countries had difficulty procuring funds and were forced to enact fiscal reforms and restructuring measures. New leaders were elected in all southern European countries as these countries changed course from lax management to reforms and austerity.

New policies in southern Europe led to a major change in the attitudes of countries in northern Europe. Initially, Germany and some northern countries seemed to have thought that Greece and other weak countries would be bound to leave the euro. They could not support hese countries unless they enacted reforms. But northern European countries subsequently adopted the position of placing the priority on preserving the euro. Substantially, Germany was the biggest beneficiary of the eurozone. German companies expanded operations to cover the entire eurozone and increased their financial influence over this region. Moreover, these companies became more competitive in other parts of the world because the euro gave them an advantage. If the euro collapsed, economic growth would end and there would be massive non-performing financial asset and serious government budget burden. Thinking in a non-emotional manner, strengthening the euro was in the national interest of Germany. At first, the people of Germany embraced the populist stance of opposing the euro. But this sentiment has been eliminated by the persistent actions of the Merkel administration.

These events are completely different than what happened during the British sterling crisis of 1992. At that time, George Soros and other speculators were victorious by using speculative sales of the pound to make the British government withdraw the pound from the European Monetary System (EMS). During this crisis, speculators orchestrated sales of the euro to force the currency’s collapse but governments did not fall into the same trap again. Why were investors unsuccessful this time? The answer is accounted for by the differences between the UK and the PIIGS. The UK has a sound industrial base and is an ally of the US with the same values as the US. Should the UK go with euro solidarity or the Atlantic alliance with the US? For the UK, which had a bat-like existence, leaving the EMS would have benefits. But for the PIIGS, losing their premier status as eurozone members would lead to a catastrophic economic downturn. The only option for these countries was to endure the pain of rebuilding their public finances and enacting reforms in order to keep the euro. The same was true of Germany, which was a source of support. All these events are clear proof that the euro currency union had already established a sufficient economic substance.

(4) The end of the euro crisis is inevitable

However, many people think that the current stability will be only temporary. They are wary because they think another crisis may start if the reins are loosened. But I believe that the possibility of another crisis has been eliminated because of major reforms to the mechanism that sparked the euro crisis. Until 2009, the euro was forced to function as a mechanism (a mechanism with no brakes or discipline) for increasing and spreading out imbalances. Today, the euro is a mechanism that automatically makes adjustments for reducing imbalances. This new mechanism requires the establishment of two elements: (1) pressure on markets by using interest rate gaps and (2) a public-sector safety net (financial channel) via the ECB.

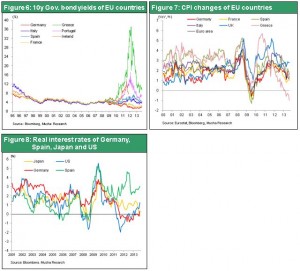

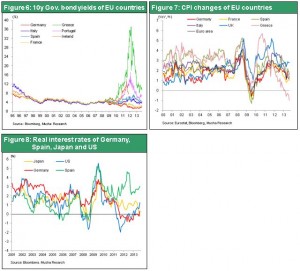

Regarding pressure on markets, Figure 6 shows that long-term interest rates in the eurozone were generally the same until 2009 despite significant differences in the rates of inflation in major European countries. As a result, real interest rates were very low in southern European countries that had a bad form of inflation. These countries fueled economic growth by using low interest rates to make excessive investments and consumption while further increasing debt. This caused imbalances to continue to grow. After the Greece shock, long-term interest rates became different in each country. Interest rates in southern Europe (Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy) skyrocketed and real interest rates became very high. Figure 8 shows the gap between real interest rates in Germany and Spain, which represents the southern European countries. As you can see, a clear change occurred in 2009. Prior to that time, real interest rates were very high in Germany and very low in Spain. Starting in 2010, though, real interest rates increased quickly in Spain while these interest rates fell to negative territory in Germany. High real interest rates made it difficult for the PIIGS to procure funds and the resulting financial crisis forced these countries to cut budget deficits and start restructuring programs.

Figure 6: 10y Gov. bond yields of EU countries

Figure 7: CPI changes of EU countries

Figure 8: Real interest rates of Germany, Spain, Japan and US

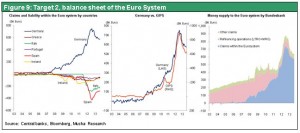

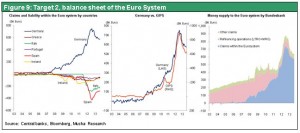

An ECB safety net is the second element. Sharply higher interest rates in the PIIGS countries blocked the circulation of private-sector funds. This raised the possibility of PIIGS insolvencies and the collapse of the euro. The crisis was ended when the ECB was used to establish an official financial framework to serve as a safety net. In Europe, an interbank settlement system called Target 2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System) became operational. In the event of an interruption in the flow of private-sector funds to finance of southern Europe countries, official financing from north to south would be used as an alternative. This would be accomplished by short-term note transactions among the central banks of eurozone countries via the ECB. Figure 9 shows how the Bundesbank alone assumed the role of channeling funds to southern Europe when there was a halt in the flow of private-sector funds to this region. Target 2 provided short-term liquidity to southern Europe. However, supplying this liquidity would be impossible if there were a full-scale of capital flight (panic selling of government bonds of southern European countries) out of southern Europe.

This situation created the need for a guarantee of long-term financing in order to restore the confidence of market participants. Several systems were established for this purpose: the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism, the European Financial Stabilization Facility and the European Stabilization Mechanism. In 2012, the ECB established the outright monetary transaction (OMT) program, consisting of unlimited purchases of the bonds of southern European countries. Announcing OMT produced a dramatic shift in market sentiment. OMT has not yet been used. However, just as with nuclear weapons, the fear created by OMT is enough to achieve the objective without actually using this weapon. Long-term interest rates have since declined and southern European countries are making progress with restructuring and rebuilding their public finances. These events have restored the flow of private-sector funds. Eventually southern European countries will probably be able to sell debt on their own again.

Figure 9: Target 2, balance sheet of the Euro System

Collectively, these developments have greatly reformed and reinforced the euro system. Soko Tanaka, a Chuo University professor who is an expert in European financial problems, has consistently pointed to two weaknesses of the euro system. First is the problem of vertical currency unification (from a mechanism for promoting polarization to a mechanism whose collapse is inevitable). Second is the absence of a safety net. But there has been significant progress with eliminating both of these weaknesses. Of course, the potential causes of another crisis that I will explain later still exist. However, long-term interest rates would immediately start climbing if a country enacted inadequate reforms or its fiscal soundness deteriorated. This would create pressure to alter policies. With the flow of private-sector funds stopped, an official safety net through the ECB would be used as a substitute (based on the premise of new reforms). This is why we can now say that the euro system has established an internal mechanism for restoring balance.

(5) The outlook for the EU and a United States of Europe

The history of European unification is rooted in reflections and soul-searching concerning the catastrophic wars in Europe over the years. Over the past 60 years, there has been steady progress: the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951; the European Economic Community in 1957; the European Monetary System in 1979; 2.25% bands for up and down currency movements (“snake in the tunnel”); the formation of the European Union in 1993 (the 1992 Maastricht Treaty), which has 28 member countries this year with the addition of Croatia; and the establishment of the euro European Central Bank in 1999, which covers 18 countries with the addition of Latvia this year.

More moves toward unification are foreseen. Agreements have been reached to establish a single supervisory mechanism for European banks and a single resolution mechanism for dealing with insolvencies. Unification of public finances may ultimately lead to the complete unification of European countries. This could result in a United States of Europe. As a result, this crisis will probably serve as a powerful springboard for moving closer to unification.

Naturally, there will always be the potential for a crisis. (1) In France, imbalances are growing because of delays in implementing reforms. The losers are receiving advantageous interest rates. (2) In Italy, there is political instability. (3) In Germany, there is an anti-growth mentality. Can Germany grow by using low real interest rates, a currency that gives it an advantage, inflows of capital and improving government finances while being a source of demand for the entire eurozone? Germany is the greatest beneficiary of the euro and the country has substantial potential for growth. Consequently, there are high expectations for more progress from the Merkel administration now that it has even more power.

(6) Financial markets still have a crisis mentality regarding Europe – There is room for a reevaluation, which creates an investment opportunity

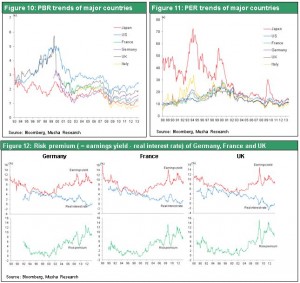

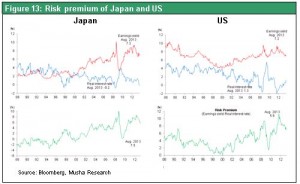

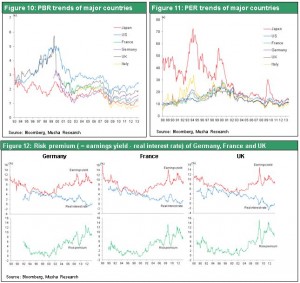

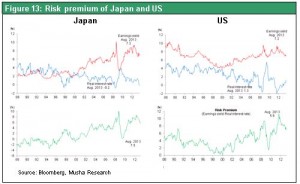

Financial markets are still worried about the possibility of the euro crisis flaring up again. Many investors are extremely skeptical about stocks in Europe. But stocks in Germany, France, the UK and other European countries are undervalued in relation to US stocks. At the end of August, the PBR for US stocks was 2.4 but only 1.8 in the UK, 1.6 in Germany, 1.3 in France and 0.9 in Italy. Japan’s PBR at that time was 1.2 (see Figure 10). At the end of August, the risk premium, which is the earnings yield minus the real interest rate, is 5.9% in the US but 8.5% in Germany, 8.4% in the UK, 7.1% in France and 7.5% in Japan, giving a sense that European and Japanese stocks are undervalued.

Once market participants reach a consensus that the euro crisis is completely in the past, we are likely to see investors reevaluate the euro and European stocks.

Figure 10: PBR trends of major countries

Figure 11: PER trends of major countries

Figure 12: Risk premium of Germany, France and UK

Figure 13: Risk premium of Japan and US

If investors conclude that the euro crisis has ended, the downward trend that is anticipated for the euro/dollar exchange rate will probably be stabilized. As you can see in Figure 14, there is a large upturn in the eurozone current account surplus. Furthermore, the US is expected to keep interest rates at almost zero until the end of 2015. That means the interest rate differential between the US and the eurozone will not widen significantly. Figure 15 shows that the downside for the euro is limited even if we believe that the euro/dollar exchange rate moves generally in tandem with changes in the interest rate differential. For many years, the dollar has been repeating a long-term cycle of five to 10 years. Currently, the dollar has ended a long-term decline that went from 2002 to 2011 and has just started a new upswing. Signs of a strengthening US economy are likely to start appearing. Extreme easy-money policies of the next year or two may finally bring full-scale job growth and then the shale gas revolution may reduce the trade deficit significantly. Once these positive signs actually surface, I believe that the upturn of the dollar will gain momentum, then the euro will be relatively weakened.

Figure 14: Successive surplus of current account balance in Euro area

Figure 15:Euro/USD exchange rate and difference of real ST interest rates between US and Euro

Figure 16: US dollar effective exchange rate trends

At the same time, there has been a major improvement in the financial soundness of governments because of extreme austerity measures. According to OECD statistics, the primary balance for government budgets (as a percentage of nominal GDP) became positive in the eurozone in 2012 and is expected to be 1.6% in 2013. In comparison, the primary balance in 2013 is expected to be -3.1% in the US, -4.3% in the UK and -8.5% in Japan. The eurozone’s performance is clearly outstanding. In previous years, surplus savings in Europe tended to flow from the north to the south in the form of financing. This created a cycle for capital in Europe as a whole. But now the demand for this financing has dropped significantly. Due to this change, long-term interest rates in southern European countries are much lower and financial markets are stabilizing. In Greece, the long-term interest rate peaked at 36% but is now below 10%. Long-term interest rates have also returned to generally pre-crisis levels in Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy. Big declines in budget deficits along with lower long-term interest rates are greatly reducing interest payments by the governments of these countries.

Figure 5: Fiscal balances of EU countries, US, UK, and Japan

At the same time, there has been a major improvement in the financial soundness of governments because of extreme austerity measures. According to OECD statistics, the primary balance for government budgets (as a percentage of nominal GDP) became positive in the eurozone in 2012 and is expected to be 1.6% in 2013. In comparison, the primary balance in 2013 is expected to be -3.1% in the US, -4.3% in the UK and -8.5% in Japan. The eurozone’s performance is clearly outstanding. In previous years, surplus savings in Europe tended to flow from the north to the south in the form of financing. This created a cycle for capital in Europe as a whole. But now the demand for this financing has dropped significantly. Due to this change, long-term interest rates in southern European countries are much lower and financial markets are stabilizing. In Greece, the long-term interest rate peaked at 36% but is now below 10%. Long-term interest rates have also returned to generally pre-crisis levels in Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy. Big declines in budget deficits along with lower long-term interest rates are greatly reducing interest payments by the governments of these countries.

Figure 5: Fiscal balances of EU countries, US, UK, and Japan

An ECB safety net is the second element. Sharply higher interest rates in the PIIGS countries blocked the circulation of private-sector funds. This raised the possibility of PIIGS insolvencies and the collapse of the euro. The crisis was ended when the ECB was used to establish an official financial framework to serve as a safety net. In Europe, an interbank settlement system called Target 2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System) became operational. In the event of an interruption in the flow of private-sector funds to finance of southern Europe countries, official financing from north to south would be used as an alternative. This would be accomplished by short-term note transactions among the central banks of eurozone countries via the ECB. Figure 9 shows how the Bundesbank alone assumed the role of channeling funds to southern Europe when there was a halt in the flow of private-sector funds to this region. Target 2 provided short-term liquidity to southern Europe. However, supplying this liquidity would be impossible if there were a full-scale of capital flight (panic selling of government bonds of southern European countries) out of southern Europe.

This situation created the need for a guarantee of long-term financing in order to restore the confidence of market participants. Several systems were established for this purpose: the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism, the European Financial Stabilization Facility and the European Stabilization Mechanism. In 2012, the ECB established the outright monetary transaction (OMT) program, consisting of unlimited purchases of the bonds of southern European countries. Announcing OMT produced a dramatic shift in market sentiment. OMT has not yet been used. However, just as with nuclear weapons, the fear created by OMT is enough to achieve the objective without actually using this weapon. Long-term interest rates have since declined and southern European countries are making progress with restructuring and rebuilding their public finances. These events have restored the flow of private-sector funds. Eventually southern European countries will probably be able to sell debt on their own again.

Figure 9: Target 2, balance sheet of the Euro System

An ECB safety net is the second element. Sharply higher interest rates in the PIIGS countries blocked the circulation of private-sector funds. This raised the possibility of PIIGS insolvencies and the collapse of the euro. The crisis was ended when the ECB was used to establish an official financial framework to serve as a safety net. In Europe, an interbank settlement system called Target 2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System) became operational. In the event of an interruption in the flow of private-sector funds to finance of southern Europe countries, official financing from north to south would be used as an alternative. This would be accomplished by short-term note transactions among the central banks of eurozone countries via the ECB. Figure 9 shows how the Bundesbank alone assumed the role of channeling funds to southern Europe when there was a halt in the flow of private-sector funds to this region. Target 2 provided short-term liquidity to southern Europe. However, supplying this liquidity would be impossible if there were a full-scale of capital flight (panic selling of government bonds of southern European countries) out of southern Europe.

This situation created the need for a guarantee of long-term financing in order to restore the confidence of market participants. Several systems were established for this purpose: the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism, the European Financial Stabilization Facility and the European Stabilization Mechanism. In 2012, the ECB established the outright monetary transaction (OMT) program, consisting of unlimited purchases of the bonds of southern European countries. Announcing OMT produced a dramatic shift in market sentiment. OMT has not yet been used. However, just as with nuclear weapons, the fear created by OMT is enough to achieve the objective without actually using this weapon. Long-term interest rates have since declined and southern European countries are making progress with restructuring and rebuilding their public finances. These events have restored the flow of private-sector funds. Eventually southern European countries will probably be able to sell debt on their own again.

Figure 9: Target 2, balance sheet of the Euro System

Collectively, these developments have greatly reformed and reinforced the euro system. Soko Tanaka, a Chuo University professor who is an expert in European financial problems, has consistently pointed to two weaknesses of the euro system. First is the problem of vertical currency unification (from a mechanism for promoting polarization to a mechanism whose collapse is inevitable). Second is the absence of a safety net. But there has been significant progress with eliminating both of these weaknesses. Of course, the potential causes of another crisis that I will explain later still exist. However, long-term interest rates would immediately start climbing if a country enacted inadequate reforms or its fiscal soundness deteriorated. This would create pressure to alter policies. With the flow of private-sector funds stopped, an official safety net through the ECB would be used as a substitute (based on the premise of new reforms). This is why we can now say that the euro system has established an internal mechanism for restoring balance.

Collectively, these developments have greatly reformed and reinforced the euro system. Soko Tanaka, a Chuo University professor who is an expert in European financial problems, has consistently pointed to two weaknesses of the euro system. First is the problem of vertical currency unification (from a mechanism for promoting polarization to a mechanism whose collapse is inevitable). Second is the absence of a safety net. But there has been significant progress with eliminating both of these weaknesses. Of course, the potential causes of another crisis that I will explain later still exist. However, long-term interest rates would immediately start climbing if a country enacted inadequate reforms or its fiscal soundness deteriorated. This would create pressure to alter policies. With the flow of private-sector funds stopped, an official safety net through the ECB would be used as a substitute (based on the premise of new reforms). This is why we can now say that the euro system has established an internal mechanism for restoring balance.

If investors conclude that the euro crisis has ended, the downward trend that is anticipated for the euro/dollar exchange rate will probably be stabilized. As you can see in Figure 14, there is a large upturn in the eurozone current account surplus. Furthermore, the US is expected to keep interest rates at almost zero until the end of 2015. That means the interest rate differential between the US and the eurozone will not widen significantly. Figure 15 shows that the downside for the euro is limited even if we believe that the euro/dollar exchange rate moves generally in tandem with changes in the interest rate differential. For many years, the dollar has been repeating a long-term cycle of five to 10 years. Currently, the dollar has ended a long-term decline that went from 2002 to 2011 and has just started a new upswing. Signs of a strengthening US economy are likely to start appearing. Extreme easy-money policies of the next year or two may finally bring full-scale job growth and then the shale gas revolution may reduce the trade deficit significantly. Once these positive signs actually surface, I believe that the upturn of the dollar will gain momentum, then the euro will be relatively weakened.

Figure 14: Successive surplus of current account balance in Euro area

Figure 15:Euro/USD exchange rate and difference of real ST interest rates between US and Euro

Figure 16: US dollar effective exchange rate trends

If investors conclude that the euro crisis has ended, the downward trend that is anticipated for the euro/dollar exchange rate will probably be stabilized. As you can see in Figure 14, there is a large upturn in the eurozone current account surplus. Furthermore, the US is expected to keep interest rates at almost zero until the end of 2015. That means the interest rate differential between the US and the eurozone will not widen significantly. Figure 15 shows that the downside for the euro is limited even if we believe that the euro/dollar exchange rate moves generally in tandem with changes in the interest rate differential. For many years, the dollar has been repeating a long-term cycle of five to 10 years. Currently, the dollar has ended a long-term decline that went from 2002 to 2011 and has just started a new upswing. Signs of a strengthening US economy are likely to start appearing. Extreme easy-money policies of the next year or two may finally bring full-scale job growth and then the shale gas revolution may reduce the trade deficit significantly. Once these positive signs actually surface, I believe that the upturn of the dollar will gain momentum, then the euro will be relatively weakened.

Figure 14: Successive surplus of current account balance in Euro area

Figure 15:Euro/USD exchange rate and difference of real ST interest rates between US and Euro

Figure 16: US dollar effective exchange rate trends