May 28, 2013

Strategy Bulletin Vol.99

The Goal of Ultra Easy-Money Policies

The shift from quantity of BRICs to quality of industrialized-countries

Japanese stocks have entered a period of volatility, although believed to be temporary, following the sharp upturn thus far in 2013. Why did stock prices drop so sharply? The reason is a touch of instability that reflects (a) slowing economic growth in China and (b) worries about economic growth in industrialized countries. The slowdown of China’s economy is becoming increasingly clear. But worries about growth in industrialized countries are based on skepticism about quantitative easing. The recent remarks by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke that the exit from quantitative easing is becoming visible sparked a resurgence of skepticism. People are worried that a winding down of quantitative easing could end the generous supply of money, leading to a surge in interest rates and downturn in stock prices and economies (as the adjustment of U.S. stocks is quite limited, skepticism for QE is most likely to be just a pretext of the fall of Japanese stocks).

I believe this consequence is unlikely to occur. But there is still no answer to the question of whether or not there will be real benefits in the wake of quantitative easing. Will the world enter a vacuum-like period where there is no growth driver as China’s economy loses momentum and industrialized country economies remain flat? Or will there be a replacement in the drivers of global economic growth? In this case, which countries will be the next sources of growth?

In industrialized countries, defensive stocks like those of consumer goods and service companies have performed well. Stocks associated with commodity goods and economically sensitive sectors like high-tech have fallen behind. A shift is taking place in the driver of global economic growth. Volume-based growth in China and other emerging countries is being replaced by growth fueled by improvements in the quality of life in industrialized countries. As this occurs, we are seeing a shift in investors’ interest in stock markets. Looking ahead, the drivers of higher stock prices are expected to be the United States and then Japan and Germany.

In industrialized countries, defensive stocks like those of consumer goods and service companies have performed well. Stocks associated with commodity goods and economically sensitive sectors like high-tech have fallen behind. A shift is taking place in the driver of global economic growth. Volume-based growth in China and other emerging countries is being replaced by growth fueled by improvements in the quality of life in industrialized countries. As this occurs, we are seeing a shift in investors’ interest in stock markets. Looking ahead, the drivers of higher stock prices are expected to be the United States and then Japan and Germany.

Surplus labor and capital were the result of an unprecedented improvement in productivity that was backed by the new industrial revolution and globalization. Companies were able to produce more goods per hour, which allowed them to use less labor and cut the cost of manufacturing. That means companies could earn more profits amid a surplus of labor and capital. According to the principles of capitalism as well as the history of mankind, higher productivity has been the driving force behind economic progress. If this is true, then the formation and destruction of bubbles is collateral evidence of rising productivity. So we should regard this formation and destruction process as milestones along the path to more economic progress.

But there is a big problem with this thinking. The more that productivity increases in a particular sector, the more likely there is to be a limit to the amount of demand. For many manufactured goods, such as smartphones and televisions, there is no need for an individual to own more than one. Consequently, no new demand will emerge beyond a certain level even if prices keep falling because of higher productivity. But is not the case for domestic-demand service sectors like education, health care, entertainment and tourism. Demand is unlimited as long as the purchasing power of consumers grows. If they have the money, people should endlessly seek even better health care, entertainment and education. However, since productivity does not improve in these sectors, there is unlimited growth in the number of jobs to meet the rising demand for these services.

Surplus labor and capital were the result of an unprecedented improvement in productivity that was backed by the new industrial revolution and globalization. Companies were able to produce more goods per hour, which allowed them to use less labor and cut the cost of manufacturing. That means companies could earn more profits amid a surplus of labor and capital. According to the principles of capitalism as well as the history of mankind, higher productivity has been the driving force behind economic progress. If this is true, then the formation and destruction of bubbles is collateral evidence of rising productivity. So we should regard this formation and destruction process as milestones along the path to more economic progress.

But there is a big problem with this thinking. The more that productivity increases in a particular sector, the more likely there is to be a limit to the amount of demand. For many manufactured goods, such as smartphones and televisions, there is no need for an individual to own more than one. Consequently, no new demand will emerge beyond a certain level even if prices keep falling because of higher productivity. But is not the case for domestic-demand service sectors like education, health care, entertainment and tourism. Demand is unlimited as long as the purchasing power of consumers grows. If they have the money, people should endlessly seek even better health care, entertainment and education. However, since productivity does not improve in these sectors, there is unlimited growth in the number of jobs to meet the rising demand for these services.

Replacing major players: The revival of the U.S. and other core industrialized countries

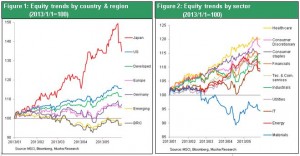

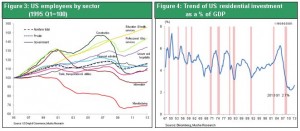

A transition is taking place in the world’s primary financial markets. In recent years, there was no room for doubt about what was perceived as the historic trend of the end of the age of industrialized countries and a shift to the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China). But stock market performance since the beginning of 2013 shows that this thinking is about to become outdated. Prices have been down this year in all the BRIC countries while stocks rallied in major industrialized countries. Stock markets are up 40% in Japan, 20% in Switzerland, 16% in the United States, 13% in the United Kingdom and 6% in Germany. Starting on May 23, Japanese stocks have posted single-day drops of a few hundred to 1,000 yen. Although a correction is occurring, most people believe that there is no change in the market’s upward direction. Figure 1: Equity trends by country & region (2013/1/1=100) Figure 2: Equity trends by sector (2013/1/1=100) In industrialized countries, defensive stocks like those of consumer goods and service companies have performed well. Stocks associated with commodity goods and economically sensitive sectors like high-tech have fallen behind. A shift is taking place in the driver of global economic growth. Volume-based growth in China and other emerging countries is being replaced by growth fueled by improvements in the quality of life in industrialized countries. As this occurs, we are seeing a shift in investors’ interest in stock markets. Looking ahead, the drivers of higher stock prices are expected to be the United States and then Japan and Germany.

In industrialized countries, defensive stocks like those of consumer goods and service companies have performed well. Stocks associated with commodity goods and economically sensitive sectors like high-tech have fallen behind. A shift is taking place in the driver of global economic growth. Volume-based growth in China and other emerging countries is being replaced by growth fueled by improvements in the quality of life in industrialized countries. As this occurs, we are seeing a shift in investors’ interest in stock markets. Looking ahead, the drivers of higher stock prices are expected to be the United States and then Japan and Germany.

How the BRICs stumbled

Looking back from today’s vantage point, we can probably say that the age of the BRIC countries was nothing more than an intermission as a series of crises occurred in the United States: the 2000 collapse of the IT bubble, the 2007 subprime loan crisis and the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers. China, the nucleus of the BRICs has revealed its heterogeneity of state capitalism as well as the difficulty in sustainable growth. To fuel even stronger economic growth, China used the easy way of relying to an extreme degree on investments. China’s investments have exceeded consumption every year since 2005, but this is no longer possible. Investments immediately make the economy larger. But if these expenditures are made for useless projects, the result will be a massive amount of bad debt. China made investments in three sectors: real estate, machinery and equipment at companies, and public-works projects. All of these investments were based on the political reasons of the Communist Party rather than economic factors. As a result, a large volume of these investments was probably wasted. Due to this situation, China has to stimulate consumption in order to replace investments as a source of economic growth. However, the country lacks the strength to boost consumption because of labor’s unusually low share of income, which is only between 40% and 49%. China appears to have finally reached a structural dead end and will be unable to avoid a slowdown in economic growth. Economic growth in Russia and Brazil as well was attributable in large part to China’s ravenous economy. The economic clout of these two countries is certain to decline as economic weakness in China causes prices of natural resources to fall. In addition, plummeting natural gas prices caused by the shale gas revolution will severely impact Russia’s economy. The BRIC countries are entering a challenging period as a result. India is the only exception because of its low reliance on China and expected growth in manufacturing backed by a weak currency and monetary easing. The emerging countries that will raise their economic growth rates in the coming years will not be large countries that want to create a world order like that of the BRIC countries. They will instead be small and midsize emerging countries like Mexico and the ASEAN countries that have an affinity for a global order based on Western European-style democracy.The revival of domestic demand and strong consumption in the U.S.

The world needs new source of demand that can replace the BRIC countries as the driver of global economic growth. If we believe that the age of economic growth fueled by the volume-based growth in emerging countries is over, then what is next? The answer is more advances involving the quality of life and domestic demand in industrialized countries. Most significantly, a broad-based economic expansion is starting in the United States, where the economy has finished its correction following the global financial crisis. U.S. housing prices are coming back after dropping 30% from the peak. An investment boom in houses that have once again become underpriced is about to begin. In addition, there is steady growth in the number of jobs in education, entertainment, health care and other service sectors as demand increases. The United States and other industrialized countries are now on the verge of an era of even more affluent living standards underpinned by the utilization of excess labor and capital. Quantitative easing by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke is about to succeed in establishing a trajectory for long-term economic growth by using surplus labor and capital for the creation of new demand. Abenomics and the unprecedented monetary easing of Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda are based on the same thinking. A weaker yen resulting from extreme easy-money policies will support export-dependent companies. Furthermore, the resulting end of deflation will probably produce significant benefits for the domestic-demand industries that support improvements in the quality of life of Japanese consumers.The historical significance of quantitative easing

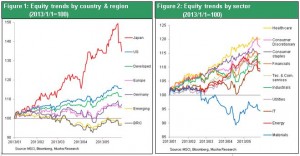

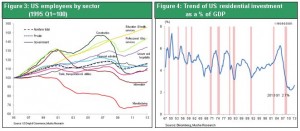

Quantitative easing is probably what made it possible to achieve a fundamental cure of the U.S. economic disease in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The reason for this belief is as follows. Why did the asset bubble burst and the global financial crisis start? Contrary to the generally accepted view, the causes of the collapse were at several levels. The direct cause was a market collapse and resulting mispricing. The root cause for that was the formation of a housing market bubble and the immoral financing activity that created this bubble. Delving even deeper reveals a still more important fundamental cause: the surplus of labor (rising unemployment) and capital (unprecedented drop in interest rates) after the end of the IT bubble in 2000. The end of the IT bubble generated enormous amounts of excess labor and capital. But these surpluses were absorbed by the housing bubble until 2007 and produced more economic growth (see Figure 3). When the housing bubble burst, the surplus labor and capital that had been temporarily absorbed by this market surfaced again. In other words, surplus labor and capital were the true cause of the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Figure 3: US employees by sector (1995 Q1=100) Figure 4: Trend of US residential investment as a % of GDP Surplus labor and capital were the result of an unprecedented improvement in productivity that was backed by the new industrial revolution and globalization. Companies were able to produce more goods per hour, which allowed them to use less labor and cut the cost of manufacturing. That means companies could earn more profits amid a surplus of labor and capital. According to the principles of capitalism as well as the history of mankind, higher productivity has been the driving force behind economic progress. If this is true, then the formation and destruction of bubbles is collateral evidence of rising productivity. So we should regard this formation and destruction process as milestones along the path to more economic progress.

But there is a big problem with this thinking. The more that productivity increases in a particular sector, the more likely there is to be a limit to the amount of demand. For many manufactured goods, such as smartphones and televisions, there is no need for an individual to own more than one. Consequently, no new demand will emerge beyond a certain level even if prices keep falling because of higher productivity. But is not the case for domestic-demand service sectors like education, health care, entertainment and tourism. Demand is unlimited as long as the purchasing power of consumers grows. If they have the money, people should endlessly seek even better health care, entertainment and education. However, since productivity does not improve in these sectors, there is unlimited growth in the number of jobs to meet the rising demand for these services.

Surplus labor and capital were the result of an unprecedented improvement in productivity that was backed by the new industrial revolution and globalization. Companies were able to produce more goods per hour, which allowed them to use less labor and cut the cost of manufacturing. That means companies could earn more profits amid a surplus of labor and capital. According to the principles of capitalism as well as the history of mankind, higher productivity has been the driving force behind economic progress. If this is true, then the formation and destruction of bubbles is collateral evidence of rising productivity. So we should regard this formation and destruction process as milestones along the path to more economic progress.

But there is a big problem with this thinking. The more that productivity increases in a particular sector, the more likely there is to be a limit to the amount of demand. For many manufactured goods, such as smartphones and televisions, there is no need for an individual to own more than one. Consequently, no new demand will emerge beyond a certain level even if prices keep falling because of higher productivity. But is not the case for domestic-demand service sectors like education, health care, entertainment and tourism. Demand is unlimited as long as the purchasing power of consumers grows. If they have the money, people should endlessly seek even better health care, entertainment and education. However, since productivity does not improve in these sectors, there is unlimited growth in the number of jobs to meet the rising demand for these services.