The Bank of Japan under its new governor Haruhiko Kuroda, who takes over on March 20, will probably destroy the curse of pessimism. The BOJ’s new direction for quantitative easing and massive purchases of Japanese government bonds and assets with risk are certain to produce a stream of positive surprises for financial markets. First, the long-term interest rate, which is already low at about 0.6%, will probably fall to the 0.4% level. Declining long-term interest rates will further highlight the undervaluation of Japanese stocks and real estate.

U.S. stock indexes have doubled since the bottom after the Lehman shock to reach new highs. Japanese stocks are very likely to rapidly follow this U.S. rally. The abnormal undervaluation of Japanese stocks will end within one year. Currently, the PBR of Japanese stocks is 1.3. If this multiple rises to the global average of 1.9, the Nikkei Average will be in the range of ¥18,000 to ¥20,000. We are also likely to see a surge in Japan’s real estate prices, which are also the most undervalued in the world. Even based on a conservative estimate, higher prices of stocks and real estate will probably generate a wealth effect (from stock and real estate capital gains) of more than ¥500 trillion in the coming few years, which is about the same as Japan’s annual GDP.

Don’t be afraid of high prices

Confusion in sentiment is increasing because of the strong rally in financial markets. Stock prices in Japan are up 40% over the four-month period since November 14 and the yen has dropped more than 20% against the dollar from ¥78 to ¥96. Abenomics is the cause. Markets have changed as if by magic. Weekly magazines are filled with articles about the stock market. This is the “spell” of Abenomics. Some people are starting to say that a bubble is forming. They are worried about the emergence of withdrawal symptoms immediately after the benefits of Abenomics fade away. Obviously the thought of buying stocks at this overheated stage following a big rally is giving investors a fear of high prices.

Figure 1: Equity indices in major countries (Mar. 2009=100)

Figure 2: Exchange rates of major currencies vs. JPY (Jan. 2007=100)

Investors have good reason to be confused. It has been a long time since there was no optimism at all in Japan and investors were selling off stocks and putting their money into cash and bonds. An anti-growth campaign is under way. Economics books that are against growth are everywhere in book stores. Another aspect is newspaper articles like the Asahi Shimbun interview on March 13 with Professor Takashi Uchiyama of Rikkyo University titled “expectations for uncontrollable money reflation are nothing more than a jointly held fantasy – don’t rely solely on money.” There is an increasing sense of discomfort among the public about the powerful stock market rally and the capital gains that appear to be easy money.

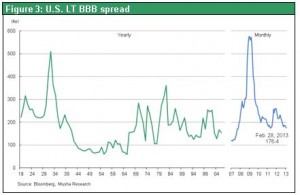

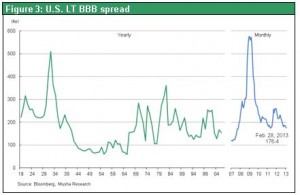

The U.S. has proven the power of the new direction of quantitative easing

People who embraced the previous pessimistic and fatalistic viewpoints were really the ones who were trapped by the spell, weren’t they? As the world recovered from the global financial crisis triggered by the Lehman shock, panic slowly quieted down and U.S. and Europe returned to normal. Only Japan was still mired in panic. In fact, there was a widespread belief that this panic was now normal. In the U.S. and Europe, government took actions aimed at achieving a recovery from the abnormal situation of panic. Quantitative easing, an unprecedented monetary policy, revived the animal spirit that had been lost and completely restored the desire to take on risk in financial markets. The risk premium (the bankruptcy rate factored in by markets) on corporate bonds that became greater than even during the Great Depression after the Lehman shock returned to the original level (Figure 3). Stock prices doubled from the March 2009 bottom and the U.S. Dow Jones Industrial Average is now at an all-time high. In Japan, stock prices remained at their Lehman shock lows up to four months ago when Abenomics emerged. Real estate prices were also consistently low.

Figure 3: U.S. LT BBB corp. bond spread

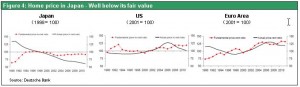

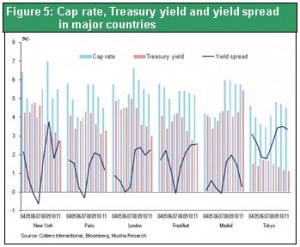

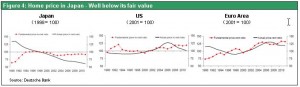

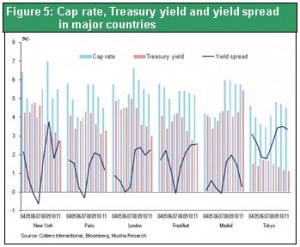

Figure 4 shows the fair value and market value of real estate in Japan, the U.S. and the eurozone in relation to rental rates. In the U.S. and eurozone, fair value and market value have generally moved in tandem except immediately after the Lehman shock. In Japan, the fair value has been mostly flat for the past 20 years but there has been a steady downturn in market values. There is clearly an enormous gap between these two values. As a result, real estate prices in Japan (Tokyo) are the lowest compared to those in major industrialized countries. Table 5 shows the yield spread between the real estate cap rate (expected return) and bond yield in major cities of the world. The yield spread is equivalent to the risk premium. As you can see, Tokyo has the highest spread in the world. These figures show that Japan has had the world’s most undervalued real estate as well as stocks.

Figure 4: Fair value and market value of real estate in Japan, the U.S. and Euro area

Figure 5: Cap rate, Treasury yield and yield spread in major countries

Japan is a follower, not a front-runner

Japan suffered from an extreme valuation gap for both stocks and real estate and Japan was the world’s only loser in terms of stock prices. In this environment, explanations that justified this situation became dominant in Japan. Simply put, this was the perception that Japan was the front-runner. The belief was that the end of a bubble is followed by a recession, deflation and prolonged economic stagnation. Many people thought that the U.S. and Europe would go down the same path that Japan started in the 1990s. During the global financial crisis after the Lehman shock, it was widely believed that Japan could give advice to the U.S. and Europe. The reason was that Japan was an “advanced country” in terms of experiencing the collapse of a bubble and subsequent deflation. In fact, the BOJ used this experience to give advice. But BOJ’s stance sparked criticism of Japan, which had become mired in deflation after the bubble burst. U.S. and European economists such as Ben Bernanke and Paul Krugman said that the cause of Japan’s problems was timid monetary easing. Afterward, though, many economists in Japan were delighted to see the U.S. and Europe follow Japan’s path and experience the demise of a bubble and a financial crisis. Former BOJ governor Masaaki Shirakawa clearly adopted this stance.

If we believe that Japan was the front-runner, then the U.S. and European economic and stock market strength is unsound and unsustainable because they are underpinned by fiscal deficit spending and abnormal easy-money policies. Upturns would eventually end, resulting in another recession and financial crisis that would bring down stock and real estate prices. In Japan, stock prices languished as a crisis mentality became the norm. People thought this was the true course of events and that the U.S. and Europe were certain to follow.

However, stock prices are climbing to new records in the U.S. and real estate prices are recovering steadily (Figure 6). There is no doubt that home prices have bottomed out. Signs of prolonged U.S. economic growth are starting to appear. Examples include progress with the shale gas revolution and IT network revolution along with full-scale rebounds in demand for houses and automobiles. The U.S. avoided deflation even during the crisis that followed the Lehman shock. Saying that the U.S. will go down the same path as Japan did is no longer a convincing argument. No longer can anyone deny the success of the new direction of financial initiatives and quantitative easing of Fed chairman Ben Bernanke.

Criticism of Abenomics is rooted in the view that quantitative easing in the U.S. and Europe will absolutely end in failure, so Japan must not do the same thing. Everyone who embraces this view bases this criticism on reasons such as the risks of sharply higher interest rates, rising inflation and growth in the moral hazard and accompanying speculation. But all of these reasons incorporate the premise that quantitative easing will fail. If sound economic growth can be restored, rising productivity will hold down inflation while raising earnings. As a result, there is no reason to expect sharply higher interest rates, rising inflation and an asset bubble.

Some people say that today’s high stock prices have created a bubble and that a spell has been cast over financial markets. However, people who make this statement are effectively confessing that they are trapped in the spell of fatalistic pessimism.

BOJ has only recently shifted to a policy centered on QE to usher in a favorable economic cycle driven by rising asset prices

The Bank of Japan under its new governor Haruhiko Kuroda, who takes over on March 20, will probably destroy the curse of pessimism. The BOJ’s new direction for quantitative easing and massive purchases of Japanese government bonds and assets with risk are certain to produce a stream of positive surprises for financial markets. First, the long-term interest rate, which is already low at about 0.6%, will probably fall to the 0.4% level. Declining long-term interest rates will further highlight the undervaluation of Japanese stocks and real estate.

U.S. stock indexes have doubled since the bottom after the Lehman shock to reach new highs. Japanese stocks are very likely to rapidly follow this U.S. rally. The abnormal undervaluation of Japanese stocks will end within one year. Currently, the PBR of Japanese stocks is 1.3. If this multiple rises to the global average of 1.9, the Nikkei Average will be in the range of ¥18,000 to ¥20,000. We are also likely to see a surge in Japan’s real estate prices, which are also the most undervalued in the world. Even based on a conservative estimate, higher prices of stocks and real estate will probably generate a wealth effect (from stock and real estate capital gains) of more than ¥500 trillion in the coming few years, which is about the same as Japan’s annual GDP.

Based on market value accounting, capital gains immediately increase funds at companies, banks and investors while dramatically raising their risk tolerance. Furthermore, these gains instantly eliminate financial restrictions on companies from international accounting standards, asset impairment accounting and other sources. This further stimulates the desire to make investments with risk exposure. The bursting of the asset bubble and the Lehman shock both generated massive destructive energy. Now, the virtuous cycle that originates with rising asset prices is about to generate positive energy of the same magnitude. Ending deflation is the mission of the BOJ under its new leadership. Accomplishing this mission will be possible only when the BOJ’s actions are accompanied by this big shift in investor sentiment.

Even now is not too late to act. Investors must realize that they have been entwined in a curse of fatalistic pessimism and recall the potential for long-term prosperity.

Figure 6: Moody’s/RCA U.S. commercial property price index

Figure 7: Market value of stocks and land in Japan

Investors have good reason to be confused. It has been a long time since there was no optimism at all in Japan and investors were selling off stocks and putting their money into cash and bonds. An anti-growth campaign is under way. Economics books that are against growth are everywhere in book stores. Another aspect is newspaper articles like the Asahi Shimbun interview on March 13 with Professor Takashi Uchiyama of Rikkyo University titled “expectations for uncontrollable money reflation are nothing more than a jointly held fantasy – don’t rely solely on money.” There is an increasing sense of discomfort among the public about the powerful stock market rally and the capital gains that appear to be easy money.

Investors have good reason to be confused. It has been a long time since there was no optimism at all in Japan and investors were selling off stocks and putting their money into cash and bonds. An anti-growth campaign is under way. Economics books that are against growth are everywhere in book stores. Another aspect is newspaper articles like the Asahi Shimbun interview on March 13 with Professor Takashi Uchiyama of Rikkyo University titled “expectations for uncontrollable money reflation are nothing more than a jointly held fantasy – don’t rely solely on money.” There is an increasing sense of discomfort among the public about the powerful stock market rally and the capital gains that appear to be easy money.

Figure 4 shows the fair value and market value of real estate in Japan, the U.S. and the eurozone in relation to rental rates. In the U.S. and eurozone, fair value and market value have generally moved in tandem except immediately after the Lehman shock. In Japan, the fair value has been mostly flat for the past 20 years but there has been a steady downturn in market values. There is clearly an enormous gap between these two values. As a result, real estate prices in Japan (Tokyo) are the lowest compared to those in major industrialized countries. Table 5 shows the yield spread between the real estate cap rate (expected return) and bond yield in major cities of the world. The yield spread is equivalent to the risk premium. As you can see, Tokyo has the highest spread in the world. These figures show that Japan has had the world’s most undervalued real estate as well as stocks.

Figure 4: Fair value and market value of real estate in Japan, the U.S. and Euro area

Figure 5: Cap rate, Treasury yield and yield spread in major countries

Figure 4 shows the fair value and market value of real estate in Japan, the U.S. and the eurozone in relation to rental rates. In the U.S. and eurozone, fair value and market value have generally moved in tandem except immediately after the Lehman shock. In Japan, the fair value has been mostly flat for the past 20 years but there has been a steady downturn in market values. There is clearly an enormous gap between these two values. As a result, real estate prices in Japan (Tokyo) are the lowest compared to those in major industrialized countries. Table 5 shows the yield spread between the real estate cap rate (expected return) and bond yield in major cities of the world. The yield spread is equivalent to the risk premium. As you can see, Tokyo has the highest spread in the world. These figures show that Japan has had the world’s most undervalued real estate as well as stocks.

Figure 4: Fair value and market value of real estate in Japan, the U.S. and Euro area

Figure 5: Cap rate, Treasury yield and yield spread in major countries