Feb 27, 2013

Strategy Bulletin Vol.93

QE has the power to destroy skepticism

The February 23 issue of Shukan Economist magazine had a feature section that seems to be out of dated: “Can monetary easing end deflation?” The dice is cast already. We have crossed the rubicon. Can monetary initiatives end deflation? Can ending deflation revive the Japanese economy? Will excessive monetary initiatives produce fatal by-products? Arguments like these are now meaningless. The Japanese government has embraced Abenomics and decided to name Haruhiko Kuroda the next BOJ governor and Kikuo Iwata the next deputy governor. The path from here on is clear. All these actions are conclusions reached because these points are now evident. First, monetary initiatives will stop deflation. Second, ending deflation will spark a recovery of the Japanese economy. And third, extensive monetary easing will not lead to fatal by-products. From now on, the people who want to be skeptical or pessimistic have no option (no way to criticize government policies) other than to continue hoping that Abenomics will fail.

On the other hand, the Japanese government and the “reborn” BOJ have no option other than to use a bazooka or any other means necessary to terminate deflation and return Japan to sound economic growth. Nothing is taboo for the government and BOJ. Financial measures must be used to stop deflation. Japan’s economy must be returned to a growth trajectory. Otherwise, the Japanese government, BOJ and Japanese economy will weaken and eventually collapse.

Financial markets will probably start factoring in the initiatives they believe that Haruhiko Kuroda, the next BOJ governor, will probably set in motion. Furthermore, the only new initiatives to choose from are actions of the new financial regime that has proven successful in the United States, United Kingdom and Europe: QE1, QE2, QE3, the ECB’s OMT*, and other measures.

* Europe has established a framework for outright monetary transactions (OMT) but is not yet using this measure. In Europe, simply the existence of OMT has caused sellers to retreat from financial markets and significantly lowered interest rates on the bonds of southern European countries. In other words, OMT has been very effective as a deterrent.

“Japan started quantitative easing before any other country. The BOJ’s assets-to-GDP ratio is already by far the highest of any developed country in the world.” This is the position of BOJ governor Masaaki Shirakawa and other believers in quantitative easing. But this is an enormous mistake. Exactly what is QE? The essence of this policy is nothing other than using a central bank to manipulate market prices (the risk premium). That means QE is used to correct mispricing that occurs when prices fall too far because of panic in financial markets fueled by mistaken pessimism and fear. The reason is that financial systems and entire economies would collapse if nothing were done. Today, market prices rather than bankers are the nucleus of credit. Manipulating market prices is therefore vital to controlling credit.

This appears to explain why central banks had to greatly expand their balance sheets. Increasing assets in order to inject massive amounts of funds was the only way to manipulate market prices. There is no doubt that the BOJ already had the highest assets-to-GDP ratio in the world. Nevertheless, the BOJ had no success at all in controlling market prices. There was no change in the abnormally high risk premium embedded in stocks and other assets with risk in Japan. The bank was unable to push up prices (lower the risk premium) of assets, including stocks.

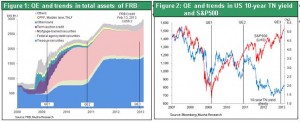

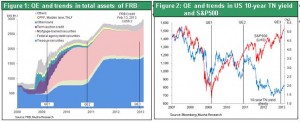

The BOJ’s actions were not at all like the successful QE of the United States, United Kingdom and Europe. Figure 1 shows the growth in the Fed’s assets. As you can see, assets increased starting in March 2009 as the Fed made massive purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) through QE1. These purchases propped up the MBS market and greatly reduced home mortgage interest rates. Next, the Fed started buying massive amounts of U.S. Treasury securities in November 2010. Making these purchases through QE2 quickly reduced the long-term interest rate from 3.5% to 2% (see Figure 2). As interest rates fell, bondholders booked enormous capital gains that served to increase investors’ appetite for risk. Rising government bond prices made stocks even more undervalued by comparison (pushing up the risk premium for stocks). In response, investors put more money into the stock market. The resurgence of U.S. financial markets was propelled entirely by the QE that produced remarkable growth of the Fed’s balance sheet. Skeptics and pessimists say that the Fed’s balance sheet growth is unhealthy. However, financial markets would not have returned to good health without this balance sheet growth. And it is impossible for a central bank to be healthy without healthy financial markets.

Mr. Kuroda will probably enact a true QE program as the new BOJ governor. The bank is likely to continue buying Japanese government bonds until a big drop in the long-term interest rate occurs (there is much downside from the current 0.7% to 0%). That will slash the risk premium on stocks (the amount by which stock returns exceed the long-term interest rate). Therefore, the BOJ will probably continue to expand its balance sheet until there is a big jump in stock prices. This is why we are certain to see stock prices surge as a correction takes place because of Abenomics and Kuroda QE.

In 1989, at the peak of Japan’s asset bubble (a positive bubble), then BOJ governor Yasushi Mieno took actions to end the bubble. Now, the next BOJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda is about to do the same thing in order to end a negative asset bubble. The BOJ in the past has taken initiatives aimed at correcting the mispricing of assets. But departing BOJ governor Masaaki Shirakawa has done nothing except sabotage measures required to perform his duty to correct asset mispricing.

(For more information about the inevitability of QE and the new role of central banks, please see Strategy Bulletin Vol. 91 “Why is Abenomics likely to be successful?”)

Figure 1: QE and trends in total assets of FRB

Figure 2: QE and trends in US 10-year TN yield and S&P500