(1) The demon of poverty has Japan in its grasp

The anti-growth mentality is justifying Japan’s current abnormal condition

Goblins are roaming Japan. They are the specters of the anti-growth mentality. The IMF and World Bank annual meeting spotlighted the problem of the risk of a global recession. The world is struggling with a severe shortage of demand as the ability to supply goods increases. Rebuilding public-sector finances is vital as well. But the annual meeting called on countries worldwide to stimulate domestic demand. Japan’s backward-looking stance regarding demand creation clearly sets the country apart from the rest of the world. Japan is the only country that is mired in deflation. Economic growth is in a state of paralysis and Japan’s stock markets continue to have the world’s worst returns. The demon of poverty, ‘anti-growth mentality’ is both the cause and symptom of this situation.

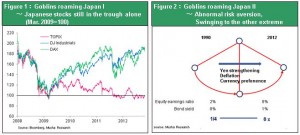

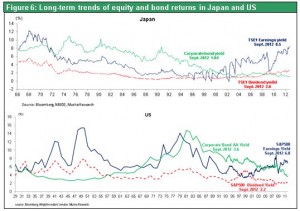

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate this problem. Although the Lehman shock should have had little impact on Japan, the country subsequently suffered the world’s steepest downturn in stock prices. Japan was not affected by the housing market bubble, euro crisis, or problem loans and inadequate capital at banks. Nevertheless, stock prices in Japan plummeted. The reason is the demon of poverty, ‘anti-growth mentality’. After stock prices hit bottom following the Lehman Brothers collapse, there have been recoveries of 100% in the United States and 90% in Germany. In Japan, however, stock prices rebounded by only 10%, far less than in the United States and Europe where the problems originated.

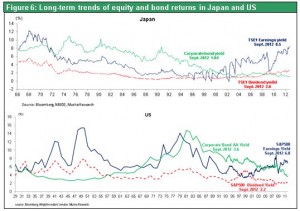

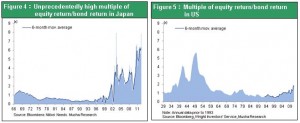

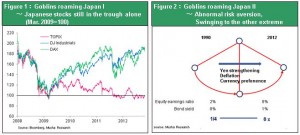

The demon of poverty, characterized by anti-growth mentality, is also responsible for preventing financial markets from functioning. The result is an abnormal aversion to risk: the earnings yield on stocks is eight times higher than the corporate bond yield. As you will see at the end of this report (Figures 4, 5, 6), the stock yield/corporate bond yield multiple, an indicator of investors’ willingness to accept risk, is now very high. This multiple was 0.25 at the peak of Japan’s asset bubble in 1990 and 0.5 at the peak of the U.S. IT bubble in 1999. Today, these multiples are 8 and 2, respectively. In the United States, the all-time high since the 1930s was 5 in 1949. Japan’s current multiple of 8 clearly demonstrates the extremely high level of risk aversion that currently exists in the country.

Figure 1:Goblins roaming Japan I ~ Japanese stocks still in the trough alone (Mar. 2009=100)

Figure 2:Goblins roaming Japan II ~ Abnormal risk aversion, Swinging to the other extreme

(2) Should Japan permit wages to fall sharply?

The spread of the irrational anti-growth mentality

In contrast to the need to stimulate demand worldwide, Japan is ruled by the anti-growth stance of sharing existing resources rather than aiming to become more affluent. The stance of Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Yukio Edano of the Democratic Party of Japan exemplifies this thinking. In a recent newspaper article, he stated that, “the modernization process that Japan has followed since the Meiji Era has finally reached its limit. Just look at the financial crisis, widening income gap and nuclear power plant accident. Japan must abandon the 'fantasy of growth’ and create an ‘anti-modernization’ society that recognizes the need to ‘allocate burdens’.” (Asahi Shimbun, October 14). A statement like this by a cabinet minister shows that the administration led by the Democratic Party of Japan is not prioritizing economic growth. In some cases, the party is even viewing growth as evil. Obviously, there is a strong ideological bias in Japan that bears no resemblance at all to the normal way of thinking in the world today. In advanced and emerging countries alike, using economic growth to create economic prosperity is the highest priority everywhere. Only Japan is embracing this completely different position. On the surface, eurozone countries appear to be concentrating on measures to reduce their deficits. In fact, southern European countries like Greece and Spain are instead currently taking steps to boost productivity in order to preserve their standards of living.

In Japan, everyone from opinion leaders to academics, bureaucrats and politicians have been poisoned by the anti-growth mentality. Mr. Edano has stated that although more resources are needed to increase the distributions of benefits, merely increasing distributions alone is acceptable. But this position is precisely the same as that of the irresponsible Social Democratic Party that supported Japan’s so-called ‘1955 System’. According to this belief, people should shun the economic efforts needed to become more prosperous. Instead, people should adopt a position of resignation as if they are convinced that there is some type of ‘dream island’ beyond the economy. Abandoning the hard work and targets needed to become more economically prosperous obviously means that people will not receive benefits that could have been earned. This mindset of resignation is probably the biggest reason that Japan’s lost decade grew to become the lost 20 years.

Disparities in Japan are the cause of deflation

Some people who think economic growth is the enemy, or place little importance on growth, and accept deflation. Do these people believe as well that Japan’s long-term decline in wages, as shown in Figure 3, was unavoidable and should be permitted? Or is there any way to enact measures to avoid this decline? Although Japan’s income disparity is small, it was created by a further downturn in wages. The large downturn in wages in the non-manufacturing sector, where wages were already relatively low, clearly demonstrates this point. On the other hand, disparities in the United States, Europe, China and other Asian countries have been created by more growth in wages among people who were already affluent. In the United States and Europe, excessive leverage and the emergence of an asset bubble most likely also contributed to widening income gaps. But these gaps do not bear any resemblance to Japan’s income gap. Deflation and the end of economic growth are responsible for disparity in Japan. Saying that the causes are financial capitalism, the bubble and excessive growth is nothing less than as if someone were stubbornly insisting that white is black. To narrow the income gap, Japan must end deflation and return to economic growth.

Figure 3:Labor compensation in Japan, US and UK(2000=100)

(3) Japan’s upcoming election is an opportunity to drive away the demon of poverty

Learning from the U.S. success story

The impact of the anti-growth mentality is enormous. This mentality erodes the desire for economic growth even among people who recognize the importance of this growth. For example, in the book ‘This Time is Different’ by Reinhart and Rogoff, the authors argue that excessive balance sheet growth and risk-taking lead to a collapse that results in slow economic growth. The book uses an absolute view of beliefs that are correct at times and incorrect at other times to reach the pessimistic and resigned conclusion that any kind of action is pointless after the bursting of a bubble. This conclusion has also become the basis of the rationale for the anti-growth mentality. According to this belief, today’s excess capital (low interest rates) and labor (high unemployment rates) are the damage caused by financial capitalism. Furthermore, people think these problems will not be easy to resolve. The Bank of Japan has been using this view of the world to proclaim that, “financial policies have reached their limit.”

However, people in Japan are no longer able to endure deflation that is linked to the yen’s strength. Japan’s multinational companies have lost their competitive edge. Workers (especially young people) are seeing their wages fall and other working conditions worsen. In the service sector, earnings are falling and companies are downsizing. Small and midsize companies in particular are no longer able to withstand these difficulties. People have become angry and are starting to make strong demands for change.

On the positive side, the United States obviously did not follow Japan’s path to deflation after the end of the asset bubble. The United States succeeded in avoiding deflation while stimulating animal spirits that fueled a stock market rally and risk-taking. Japan can learn from this experience. This success story clearly shows that the Bank of Japan’s decision to watch deflation by standing on the sidelines was a mistake. Even after cutting interest rates to almost nothing, the Bank of Japan has unlimited options for other financial actions and can continue to support risk-taking. Once a central bank becomes a risk-taker itself, surrender is the only course of action for people who had been shunning risk. In Japan as well, quantitative easing and central bank asset purchases should lower the risk premium and encourage people to make investments. Taking these steps would be very likely to start a powerful virtuous cycle.

Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda has promised to dissolve parliament in the near future. A general election will probably take place late this year or early in 2013. An election will probably result in a major defeat for the Democratic Party of Japan, which was unable to evolve into a responsible party with realistic policies. There are many issues: economic problems; the inability of Japan’s high-tech companies to compete; China’s increasing power, as demonstrated by the Senkaku Islands dispute; a decline in Japan’s global influence; and the changing view of the security alliance with the United States. The political agenda is clear and there is a single vector of public opinion. The time has come for Japan to eliminate the remnants of the ‘1955 System’. Japan must become an ordinary country by eradicating the anti-growth mentality with regard to national security and the economy.

Criticism of the Bank of Japan is intense. The bank will probably have to make a policy shift now that the term of Governor Masaaki Shirakawa is about to end. If there is a shift, it will probably be the start of a major change of direction for Japanese stocks.

Japan can play a central role in global demand creation. Three conditions for growth are in place. First is a massive volume of idle capital. Second is a huge volume of invisible unemployment (young people as well as women, older people and others). Third are the many unfilled demands among consumers (living standards are still low). Furthermore, since assets in Japan have become extremely undervalued, a correction of these asset prices would generate huge capital gains. If the PBR of Japanese stocks simply increases from the current 0.9 to the world average of 1.7, stock prices would double. This would raise Japan’s stock market capitalization by more than ¥200 trillion. There is substantial room on the upside for real estate prices, too.

The global economy continues to expand at only a moderate pace. In a worldwide environment of extreme easy-money policies, there will be no end to investors’ pursuit of assets with risk. As investors around the world continue to seek untapped places to invest, they will undoubtedly stop when they reach the virgin territory of Japan, which has one of the most attractive economies and markets in the world.

Figure 4:Unprecedentedly high multiple of equity return/bond return in Japan

Figure 5:Multiple of equity return/bond return in US

Figure 6: Long-term trends of equity and bond returns in Japan and US