Oct 18, 2012

Strategy Bulletin Vol.81

Why is ending deflation the most important structural policy?

- Japan must shift its focus to domestic demand and away from reliance on China -

● Japan should stop relying on China and other overseas markets and instead create demand on its own. There is much potential for creating demand because Japan has substantial idle labor and capital.

● Ending deflation will be vital to create domestic demand. The structural policy must be directing idle labor and capital to sectors where latent demand exists. Inflation is the most effective means of accomplishing this. Deflation is the reason that Japan was no longer able to reallocate its resources, which resulted in people and money with nothing to do.

● Japan must create jobs by shifting the benefits (earnings) of rising productivity in the high-tech and other sectors to the service sector. Accomplishing this will require inflation for the cost of services. In the United States, continuing inflation in the service sector has produced jobs and generated domestic demand. But in Japan, prices of services are declining. This deflation is preventing the redistribution of income to domestic-demand industries, so no jobs or demand has been produced.

● Deflation fuels an extreme preference for currency that prevents financial markets from functioning as a source of risk capital.

● The yen’s strength is the greatest cause of deflation. The global labor market is ruled by the law of one price and the principle of paying the same wage for the same work. If a country raises wages without an improvement in productivity, the country will be punished with inflation that devalues the currency. In other words, wages worldwide will all return to the average level. Similarly, if a country’s currency strengthens without a commensurate rise in productivity, the result will be falling wages that bring the country’s salaries to the global level. The relentless strength of the yen has created prolonged downward pressure on wages in Japan. This is why Japan alone in the world is suffering from deflation.

● Japan must implement creative and massive monetary easing in order to stop the yen from appreciating and break away from deflation.

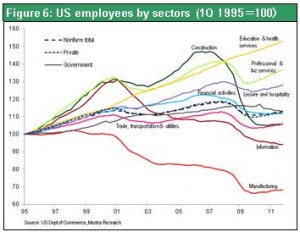

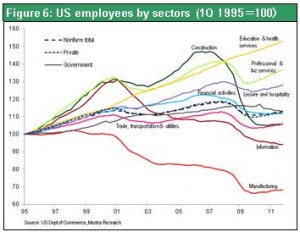

Figure 6 shows the number of jobs by sector in the United States since 1995. During the past 15 years, the U.S. manufacturing and information industries, which were the drivers of income creation (economic growth), have achieved a big increase in labor productivity (physical productivity) but there was a sharp drop in employment. On the contrary, the U.S. education and health care, entertainment, and services, etc. sectors, which apparently no significant increase in labor productivity (physical productivity), recorded big increases in employment.

Income was transferred from the manufacturing and information industries to service industries. This enabled the service sector to constantly secure the income needed to create more jobs. Service price inflation was the primary path for this income transfer.

Deflation has fueled an extreme preference for currency that prevented financial markets from functioning as a source of risk capital. Over 20 years of deflation in Japan, deflation along with falling prices of stocks, land and other assets firmly established a “cash is king” mentality. The result was an extreme aversion to risk. No capital at all was directed to assets with risk. Stock failed to attract capital even though stock earnings yields rose to 8%, eight times higher than the 1% yield for corporate bonds. Capital was merely locked up as cash and interest rate arbitrage came to a halt.

Figure 6: US employees by sectors (1Q 1995=100)

Figure 6 shows the number of jobs by sector in the United States since 1995. During the past 15 years, the U.S. manufacturing and information industries, which were the drivers of income creation (economic growth), have achieved a big increase in labor productivity (physical productivity) but there was a sharp drop in employment. On the contrary, the U.S. education and health care, entertainment, and services, etc. sectors, which apparently no significant increase in labor productivity (physical productivity), recorded big increases in employment.

Income was transferred from the manufacturing and information industries to service industries. This enabled the service sector to constantly secure the income needed to create more jobs. Service price inflation was the primary path for this income transfer.

Deflation has fueled an extreme preference for currency that prevented financial markets from functioning as a source of risk capital. Over 20 years of deflation in Japan, deflation along with falling prices of stocks, land and other assets firmly established a “cash is king” mentality. The result was an extreme aversion to risk. No capital at all was directed to assets with risk. Stock failed to attract capital even though stock earnings yields rose to 8%, eight times higher than the 1% yield for corporate bonds. Capital was merely locked up as cash and interest rate arbitrage came to a halt.

Figure 6: US employees by sectors (1Q 1995=100)

(1) The urgent need to stimulate domestic demand Anti-Japan demonstrations show the need for creating domestic demand

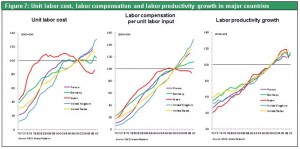

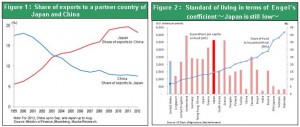

The IMF and World Bank annual meeting raised public awareness of the risk of a global recession. Currently, the world is struggling with the problem of growth on the supply side along with a severe shortfall on the demand side. Rebuilding the public-sector finances is important. But the annual meeting is also calling on countries to stimulate domestic demand. There is a particularly great need to create demand in Japan. First, Japan has significant potential for generating domestic demand. As the only country in the world with deflation, Japan has an excess of resources (equipment, capital, labor) on the supply side. That means Japan can create demand if these idle resources can be utilized, which would produce more economic growth. Second, Japan should use the demand creation process fueled by domestic demand in order to contribute to the global economy. All countries of the world have inadequate demand that is making them increasingly reliant on external demand. If a country decides to respond by making its currency cheaper and exporting products at below cost (dumping), this would merely equate to a policy of exporting deflation to neighboring countries. The result would be a trade war and global instability. These events even lead to visions of a Great Depression and political standoffs among countries. China has created an excess supply on an unprecedented scale and is beginning to export deflationary pressure to the world. Now is the time for Japan to rely on itself rather than others for actions that will strengthen its economy. Anti-Japan demonstrations and riots in China show the risk of a global recession centered in China as well as the limitations of globalization. Looking back, Japan itself has used external demand since 2000 for the purpose of ending an economic crisis. Growing exports to China were the driving force behind this process. As you can see in Figure 1, there has been rapid growth in Japan’s exports to China of goods for further processing. At the same time, though, Japan has fallen sharply as a percentage of China’s exports. This explains why China is exaggerating that if the current tension with Japan has a negative economic impact, Japan will suffer more than China. As long as there is no hope for an end to China’s political risks (criticism of Japan, political and social instability in China, etc.), Japan will have to stimulate domestic demand even more and reduce its dependence on China.Japan has a remarkably low living standard; the potential improvement is great

The primary roles of industrialized countries in association with globalization are creating new demand, developing new life styles, and leading the way in creating an even more advanced standard of living. Among advanced countries, Japan has a fairly low living standard. In fact, there is widespread support for the anti-growth stance of sharing what Japan already has rather than aiming for more affluence. However, this is merely the thinking of people who do not understand the ways of the world. The position of Yukio Edano, a member of the Democratic Party of Japan and Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, exemplifies this thinking. In his recent book, Mr. Edano said “Japan has reached the limit of the modernization process that started in the Meiji Period. Just look at the financial crisis, the widening gap between rich and poor, and the nuclear power plant accident. Japan must abandon the “growth fantasy” and accept the need for the “allocation of burdens” in order to create a society that “breaks away from modernization.” (October 14, 2012, Asahi Shimbun article) The service sector is vital to improving Japan’s living standard as well as to the lives of the people of Japan. Why aren’t services profitable? Why can’t the service sector create jobs? These are the questions that Japan must answer. Figure 1: Share of exports to a partner country of Japan and China Figure 2: Standard of living in terms of Engel's coefficient ~ Japan is still low ~

(2) Ending deflation is the greatest structural policy = Measures to stimulate domestic demand The fundamental mistake of Mr. Shirakawa

In Japan, some people believed that structural reforms were needed. There was a belief that Japan could not increase its economic growth rate by using cyclical policies like financial measures and demand stimulation. However, this is an enormous mistake. Earlier this year, Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa made the following statements. “Japanese people must tackle problems head on while the central bank uses monetary easing to ease the pain. This requires a system of values consistent with the economy’s metabolism along with decisive reforms for regulations and systems for accommodating new demand.” “Some consumers say it is all right to pay high prices in sectors where latent demand is growing along with Japan’s aging population. On the other hand, for existing products, we are seeing immense competitive pressure on cost and prices. Downsizing the ’red ocean’, which is the limited pie where intense competition is taking place, and expanding the ’blue ocean’ of new markets is the process for ending deflation.” (May 13, 2012, Asahi Shimbun) Mr. Shirakawa is saying that ending deflation and boosting economic growth will require directing resources to growing sectors (sectors with latent demand). But he believes these are structural measures that are not included in the roles of financial policies.Productivity-gap inflation is the path to the redistribution of income

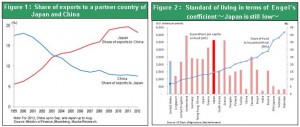

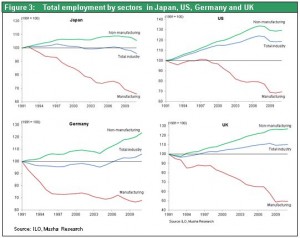

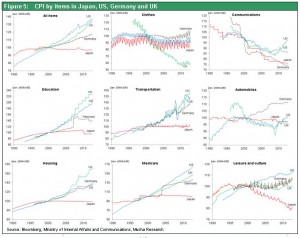

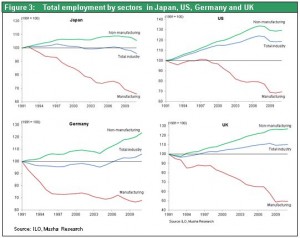

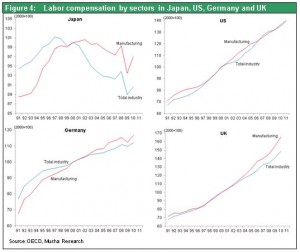

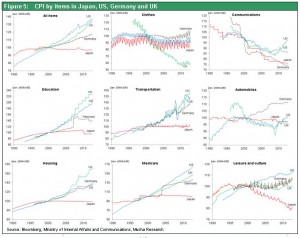

Resources must be allocated as much as possible (gather as much capital as possible for generating earnings) to growth sectors in Japan (sectors where demand and employment are expected to grow). However, deflation has been the greatest barrier to achieving the optimum distribution of resources. This is why redistributing income will be impossible without inflation. Looking back to Japan’s period of rapid economic growth clearly demonstrates this point. Japan’s standard of living improved rapidly along with technological innovation and rising productivity. Income disparities between cities and rural areas and between the manufacturing and service sectors narrowed. This was possible because income earned in manufacturing and other high-productivity sectors was shifted to the service and agricultural sectors by raising prices for services and agricultural products. This can be called “productivity improvement rate gap inflation.” When service sector inflation ended, it was also the end of Japan’s redistribution of income. Growth of the service sector and its jobs ceased. Figure 3 shows how employment in the manufacturing and service sector has changed in Japan, the United States, Germany and United Kingdom. As you can see, non-manufacturing employment is flat only in Japan. Service price deflation is the cause. Figure 5 shows changes in prices for specific categories. Prices of manufactured goods have declined in all countries. But Japan alone has experienced a drop in prices of services while these prices have posted sharp increases in other countries. As you can see in Figure 4, wages as well have declined only in Japan. The downturn is particularly steep in the non-manufacturing sector. Obviously, service price deflation is leading to falling earnings, wages and employment in Japan’s service sector. Figure 3: Total employment by sectors in Japan, US, Germany and UK Figure 4: Labor compensation by sectors in Japan, US, Germany and UK Figure 5: CPI by items in Japan, US, Germany and UK

Figure 6 shows the number of jobs by sector in the United States since 1995. During the past 15 years, the U.S. manufacturing and information industries, which were the drivers of income creation (economic growth), have achieved a big increase in labor productivity (physical productivity) but there was a sharp drop in employment. On the contrary, the U.S. education and health care, entertainment, and services, etc. sectors, which apparently no significant increase in labor productivity (physical productivity), recorded big increases in employment.

Income was transferred from the manufacturing and information industries to service industries. This enabled the service sector to constantly secure the income needed to create more jobs. Service price inflation was the primary path for this income transfer.

Deflation has fueled an extreme preference for currency that prevented financial markets from functioning as a source of risk capital. Over 20 years of deflation in Japan, deflation along with falling prices of stocks, land and other assets firmly established a “cash is king” mentality. The result was an extreme aversion to risk. No capital at all was directed to assets with risk. Stock failed to attract capital even though stock earnings yields rose to 8%, eight times higher than the 1% yield for corporate bonds. Capital was merely locked up as cash and interest rate arbitrage came to a halt.

Figure 6: US employees by sectors (1Q 1995=100)

Figure 6 shows the number of jobs by sector in the United States since 1995. During the past 15 years, the U.S. manufacturing and information industries, which were the drivers of income creation (economic growth), have achieved a big increase in labor productivity (physical productivity) but there was a sharp drop in employment. On the contrary, the U.S. education and health care, entertainment, and services, etc. sectors, which apparently no significant increase in labor productivity (physical productivity), recorded big increases in employment.

Income was transferred from the manufacturing and information industries to service industries. This enabled the service sector to constantly secure the income needed to create more jobs. Service price inflation was the primary path for this income transfer.

Deflation has fueled an extreme preference for currency that prevented financial markets from functioning as a source of risk capital. Over 20 years of deflation in Japan, deflation along with falling prices of stocks, land and other assets firmly established a “cash is king” mentality. The result was an extreme aversion to risk. No capital at all was directed to assets with risk. Stock failed to attract capital even though stock earnings yields rose to 8%, eight times higher than the 1% yield for corporate bonds. Capital was merely locked up as cash and interest rate arbitrage came to a halt.

Figure 6: US employees by sectors (1Q 1995=100)

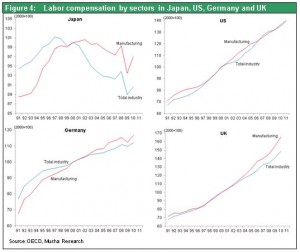

(3) The strong yen created deflation and dealt the service sector a severe blow The global labor is ruled by the law of one price

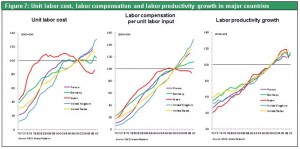

The yen’s strength is the greatest cause of deflation. The global labor market is ruled by the law of one price and the principle of paying the same wage for the same work. If a country raises wages without an improvement in productivity, the country will be punished with inflation that devalues the currency. In other words, wages worldwide will all return to the average level. Similarly, if a country’s currency strengthens without a commensurate rise in productivity, the result will be falling wages that bring the country’s salaries to the global level. The relentless strength of the yen has created prolonged downward pressure on wages in Japan. This is why Japan alone in the world is suffering from deflation. You can clearly see this in Figure 7, which shows wages and unit labor cost in selected countries. Even though Japan has the best performance in terms of labor productivity among all the major countries, wages in Japan are falling. As a result, on a local currency basis, only Japan is experiencing a rapid decline in unit labor cost. Switching to a dollar-based comparison of unit labor cost makes Japan’s figures about the same as those of other countries. Consequently, the extreme strength of the yen has been holding down wages in Japan. As a result, measures to prevent the yen from appreciating and a decline in the yen’s value will create upward pressure on wages in Japan. This is why Japan must implement creative and massive monetary easing in order to end deflation. No country in the world has more potential for creating demand than Japan. In Europe and the United States, troubled financial assets and insufficient bank capital are holding back economic growth. But Japan does not have these problems. Furthermore, there are potentially huge capital gains in Japan from a correction in asset prices that have dropped far too much. If Japanese stock prices simply increase from the current PBR of 0.9x to the global average of 1.7x, prices would almost double. That translates into an increase in market capitalization of more than \200 trillion. A rally like this would probably spark a resumption of risk-taking and interest rate arbitrage in financial markets that could end deflation. Now more than ever Japan must enact financial policies with a focus on bringing down the yen and increasing investments in assets like stocks and real estate. Through these measures, Japan should aim to use the creation of demand to make a contribution to the health of the global economy. Figure 7: Unit labor cost, labor compensation and labor productivity growth in major countries