(1) Japan alone among countries with a trade surplus is allowing the market to determine the value of its currency

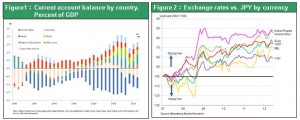

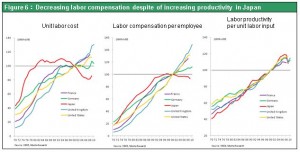

Unification of the global economy is progressing as market-based economies take over the world. At the same time, we are seeing growth in activities that hinder market forces. Examples include national capitalism (China is the prime example) and measures to manipulate and guide foreign exchange rates. Both national capitalism and foreign exchange market manipulation restrict economic growth by distorting the efficient allocation of resources on a global scale and preventing the effective utilization of capital and labor. Since the floating exchange rate system emerged, these rates have apparently been determined in a rational manner by market forces. However, rates are actually closely tied to national interests. In particular, a structure has recently been created that prevents foreign exchange rate corrections from occurring for the currencies of China, Germany and South Korea, the world’s big three in terms of trade surplus growth. In China, the yuan is still virtually pegged to the U.S. dollar. Germany has a huge trade surplus but is still benefiting from the euro’s weakness. South Korea continues to use artificial measures to hold down its currency in order to become more competitive (see Figures 1 and 2). During the difficult period after the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers, the United States supported its economy and the corporate sector by using massive monetary easing and weakened the dollar. Furthermore, China appears to have started guiding the yuan downward to bolster its economy. Overall, many countries of the world have been controlling foreign exchange rates to obtain benefits. Among the world’s major trade surplus countries, only Japan is willing to let the market decide the value of its currency. As a result, investors have had no alternative to buying the yen alone among major currencies.

Figure1: Current account balance by country, Percent of GDP

Figure2: Exchange rates vs. JPY by currency

(2) Japan’s economy distorted by strength of excessive speculation in the yen

Furthermore, Japan is the only country in the world with deflation (which means the currency’s value is increasing). And only Japan has a central bank with a neutral stance regarding the value of the currency. Therefore, the yen alone among major currencies continues to climb because it is the target of currency speculation resulting from the process of elimination. From the mid-1980s until about 2000, Japan consistently posted large trade surpluses because of its competitive edge in global markets. During that time, the yen’s strength was viewed as an unavoidable handicap for Japan. Since then, Japan has become much less competitive. Moreover, in the first half of 2012, Japan recorded its historic trade deficit (\2.9 trillion) as fuel imports surged after the country’s nuclear power plants went off line. But the yen has remained strong even after this deficit. Foreign exchange rates can easily move by 10% to 20% over a short time in order to quickly make a big change in a country’s ability to compete in global markets. Movements in these rates are far greater than changes in tariffs and other factors affecting international trade. Countries often work hard on becoming more globally competitive by using tariff negotiations, establishing the Trans-Pacific Partnership and taking other actions. However, there is a significant risk of losing all benefits from these actions if a country’s foreign exchange rate moves in the wrong direction.

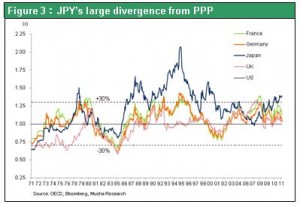

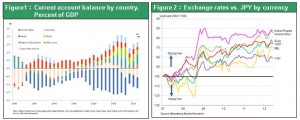

As you can see in Figure 3, the too large gap between the yen’s exchange rate and its actual strength (purchasing power parity) has been the source of considerable pain and distortions in the Japanese economy. For example, (1) some manufacturers in Japan lost their competitive edge; (2) prices of assets have declined along with deflation; and (3) the allocation of resources in Japan has become distorted and unfair. A prime illustration is the increasingly advantageous position of public-sector workers and pension recipients as the wages of private-sector workers fall.

Figure 3: JPY’s large divergence from PPP

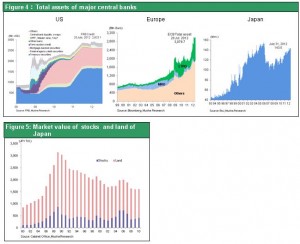

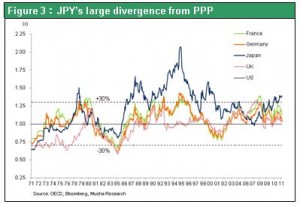

(3) BOJ’s quantitative easing measures will be decisive

If nothing is done, Japanese industry will lose its competitive edge to other countries. Now is the time for Japan to take control of its currency. But the decision to join the ranks of countries intervening in foreign exchange markets would subject Japan to criticism. This is why the BOJ should increase base money by implementing a significant monetary easing program while allowing its balance sheet to grow. Central banks worldwide are beginning to shift their focus from manipulating interest rates to enacting quantitative easing. The BOJ should be at the forefront of this trend. All the BOJ needs to do is increase base money by making large purchases of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and REITs. Countries struggling with insufficient demand should welcome Japan’s use of quantitative easing to achieve reflation. Ending the yen’s deflation-backed strength and pushing up prices of assets will add significant purchasing power to Japan’s domestic demand. These events will probably trigger a dramatic shift in the Japanese economy.

Figure 4: Total assets of major central banks

Figure 5: Market value of stocks and land of Japan

Appendix 1 - A weaker yen will boost wages and increase domestic demand.

Foreign exchange movements are immediately reflected in wages and real estate prices, which are cost components unique to each country. For instance, for the same labor (productivity) and same wages, a doubling of the yen’s strength would double wages in Japan in relation to other countries. The result would be pressure in Japan to cut wages by half. This would bring wages in Japan back to the international level in accordance with the law of one price. A stronger yen automatically exerts downward pressure on wages and creates deflation. A weaker yen has the opposite effect of automatically raising wages and producing inflationary pressure.

Appendix 2 - Strong-yen deflation has distorted Japan’s income allocation.

Since the 1980s, Japan had huge trade surpluses because its companies were extremely competitive. Are we correct to view the yen’s strength as an unavoidable penalty for having this destructive competitive superiority? Not necessarily. Inflation was another way to make Japanese companies less competitive. Perhaps Japan could have chosen a different path that would not have destroyed the financial bubble and thus would have increased wages and avoided a strong yen.

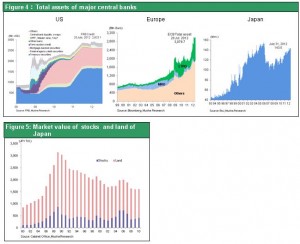

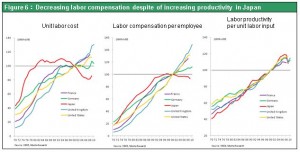

Figure 6: Decreasing labor compensation despite of increasing productivity in Japan

In the early 1990s, Japan had two options for responding to the sequence of events in which rising productivity made Japanese companies more competitive, thereby further increasing the trade surplus (increasing income).

(1) Return the income to workers by raising their wages = Become less competitive

(2) Use a stronger yen to transfer income to importers, thereby increasing their purchasing power for overseas goods = Become less competitive

Both options influence income distribution in Japan through (1) wage inflation or (2) deflation. As a result, there should have been a conflict of interest. However, there are no signs that confirmations were conducted at that time regarding the interests of different sectors or the selection of policies. Ultimately, option (2) was chosen. This decision led to deflation linked to a stronger yen, which held down income for workers, thereby limiting domestic demand, and raised the relative incomes of public-sector workers and public-sector pension recipients. Selecting option (2) also increased the pace of globalization at Japanese companies, which was accompanied by these companies placing more emphasis on added value and distinctive products.

In the early 1990s, Japan had two options for responding to the sequence of events in which rising productivity made Japanese companies more competitive, thereby further increasing the trade surplus (increasing income).

(1) Return the income to workers by raising their wages = Become less competitive

(2) Use a stronger yen to transfer income to importers, thereby increasing their purchasing power for overseas goods = Become less competitive

Both options influence income distribution in Japan through (1) wage inflation or (2) deflation. As a result, there should have been a conflict of interest. However, there are no signs that confirmations were conducted at that time regarding the interests of different sectors or the selection of policies. Ultimately, option (2) was chosen. This decision led to deflation linked to a stronger yen, which held down income for workers, thereby limiting domestic demand, and raised the relative incomes of public-sector workers and public-sector pension recipients. Selecting option (2) also increased the pace of globalization at Japanese companies, which was accompanied by these companies placing more emphasis on added value and distinctive products.

In the early 1990s, Japan had two options for responding to the sequence of events in which rising productivity made Japanese companies more competitive, thereby further increasing the trade surplus (increasing income).

(1) Return the income to workers by raising their wages = Become less competitive

(2) Use a stronger yen to transfer income to importers, thereby increasing their purchasing power for overseas goods = Become less competitive

Both options influence income distribution in Japan through (1) wage inflation or (2) deflation. As a result, there should have been a conflict of interest. However, there are no signs that confirmations were conducted at that time regarding the interests of different sectors or the selection of policies. Ultimately, option (2) was chosen. This decision led to deflation linked to a stronger yen, which held down income for workers, thereby limiting domestic demand, and raised the relative incomes of public-sector workers and public-sector pension recipients. Selecting option (2) also increased the pace of globalization at Japanese companies, which was accompanied by these companies placing more emphasis on added value and distinctive products.