(1) A rapid slowdown - China shifts course by resuming investments

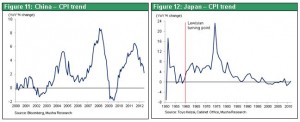

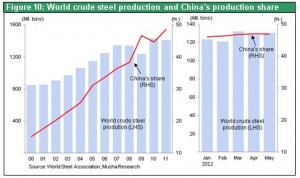

The concern buoys that economic growth in China is slowing rapidly. GDP has been expanding at an annual rate of more than 10% for the past several years. But annualized growth fell to 8.1% in the first quarter of 2012 and to 7.6% in the second quarter. In June, China’s electricity generation and crude steel production were both the same as one year earlier and ethylene production was down. The causes are monetary tightening and declining exports linked to global economic problems, especially falling demand in Europe. In part because of political demands in this year of a transition in political power in China, the government has started monetary easing and restarted some public-works projects that had been suspended. Furthermore, the Chinese government has given Baosteel Group Corporation and Wuhan Iron and Steel (Group) Corporation permission to begin construction of two steel mills that had been awaiting approval. By taking actions like these, the government is stepping up efforts to bolster the economy. For the time being, China’s economic growth rate will probably stop falling, in part because of the benefits of an improvement in net exports due to the healthy U.S. economy and falling cost of crude oil.

Figure 1: China - real GDP growth

Figure 2: China - crude steel production growth

Figure 3: China - electricity production growth

Figure 4: China - import and export growth and trade balance

China’s growth hits a wall - The urgent need to boost consumption by rapidly shifting income distribution

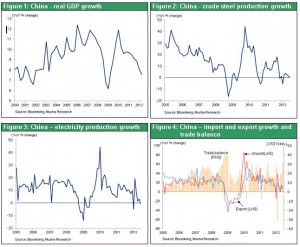

The Chinese economy has most likely reached a major turning point. Over the medium-term, a slowdown in the growth rate is unavoidable. The first reason is that the country’s growth model that relies on investments and exports has run its course. The second reason is a shift in the population. Within the next year or two, China’s working-age population (age 15 to 64) will begin to decrease. The third reason is that China has reached the growth barrier that was always its inevitable fate. With a per capita national income of $4,000, China has become a middle-income nation. China can no longer grow by using resources, which is a characteristic unique to the rapid-growth years of emerging countries. The country has reached the point where it must switch to economic growth fueled by technological progress.

At this key turning point, China should make a rapid shift in the distribution of income to trigger strong growth in consumption. China must eliminate income inequalities by raising labor’s share of income and allocating more income to agricultural villages and the service sector. Adopting a stance of boosting economic growth by further raising investments rather than increasing consumption would be a mistake. China would simply be committing the crime of making more excessive investments on top of past excessive investments. Steps like restarting expressway construction, building steel mills even though China has too much output capacity, and making real estate loans easier to obtain would probably lead to serious problems in the future.

Figure 5: Workforce trend forecast by country

Figure 6: China - current GDP per capita trend

(2) China’s strong centralization of resources towards its excessive investments

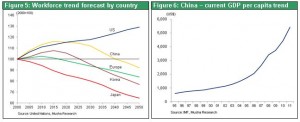

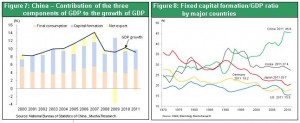

China faces enormous difficulties with regard to breaking away from the emerging country growth model. Economic growth has been almost entirely dependent on investments and exports. But now signs are emerging of the end of an economy underpinned by large investments and high gearing. First, China can no longer maintain the unusually high level of reliance on investments and exports (approximately 60%) that supported economic growth during the past decade. Second, China’s fixed capital formation/GDP ratio rose to 46% in 2011, a level higher than ever seen in any country. Investments have surpassed consumption at an accelerating pace since 2005. But this situation as well cannot continue. Focusing resources on the creation of an economy driven by investments and exports can temporarily raise the economic growth rate (ability to supply goods). In fact, this phase of economic growth occurred in both Japan and South Korea. However, relying on this type of growth makes it very difficult to achieve a soft landing that results in sustainable growth in demand and an improvement in the standard of living.

Figure 7: China - Contribution of the three components of GDP to the growth of GDP

Figure 8: Fixed capital formation/GDP ratio by major countries

A labor and capital utilization framework that is not economically rational

Market mechanisms do not function as a check for economic policies in China. As a result, contradictions have become increasingly serious as large volumes of labor and capital are used for economic growth fueled by substantial investments and gearing. In terms of labor, China has shifted surplus workers from the agricultural sector to companies while holding down growth in wages (cheap labor prior to the Lewisian turning point). The large profits at companies that resulted from the use of this cheap labor were the source of China’s substantial investments. Furthermore, China had no market mechanism for determining wages because of the use of outdated systems like the family register system. These systems prevent the country from ending low wages (low labor share of income) and lackluster consumer spending.

With regard to the utilization of China’s large volume of capital, there has been no change in the excessive allocation of resources due to the superficially high profit margins of companies (resulting from the use of cheap labor) and the monopolistic pricing and preferential financing for the public sector. Savings among workers in China are high because of worries about the reliability of government social security programs. But since bank deposits pay almost no interest in the real term, these savings are actually a means of transferring income to borrowers. The interest rate margin between deposits and loans at banks is steady. Furthermore, since lending is influenced primarily by government policies rather than economic considerations, there has been no change in the pattern of loans to the public sector flowing into real estate investments. Consequently, there is absolutely no interest arbitrage for investments.

All of these characteristics point to a mechanism in which investments continue to climb without any type of verification for the expected returns on those investments. In other words, China appears to have become an investment machine with no brakes. This has created many problems: excessive capital expenditures at government owned companies in the heavy and chemical industry sector; large infrastructure investments in the rural part of China; and a bubble involving real estate developments organized by local governments. Funds procured by local governments through joint public-private sector ventures were channeled to real estate development companies. Land utilization payments by these developers then became the primary source of funds for local governments. This explains why so many real estate developments in China became mired in the activity trap, in which the project’s original objectives are forgotten.

Figure 9: China - Investment for real estate development; growth is getting slow.

The problems created by excessive investments

From the standpoint of economics and accounting, investments are nothing more than an expenditure that can be treated as an expense at some point in the future. The only certain thing about an investment is that it will create an expense in the future. No one knows if the investment will generate a return. This is why differences in expectations can cause a crisis. The accounting definition of an investment is very different from the generally accepted concept of an investment. Large investments result in higher depreciation expenses and an increase in the capital coefficient (worsening efficiency of capital expenditures). If investments fail to generate the expected cash flows, there is very likely to be an increase in non-performing assets. For example, over a period of less than 10 years, China will make an enormous investment to construct an expressway network that is five times larger than the Shinkansen network in Japan. But now there are increasing worries about these highways becoming non-performing assets because of low utilization rates and concerns about safety. Precisely the opposite situation exists in the United States as consumption continues to climb as a percentage of GDP. On the surface, rising consumer spending appears to be holding down expenditures for future growth. However, growth in expenditures for the future that are not recorded as assets, such as for education and software development, accounts for a large share of the increase in U.S. consumption. Therefore, the United States is making expenditures for the future that are treated as expenses now. But China is increasing investments in projects that are likely to become non-performing assets. Which country has a sounder economy? The answer is obvious.

(3) No progress with the essential shift in the structure of distribution

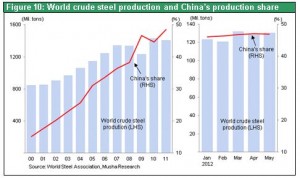

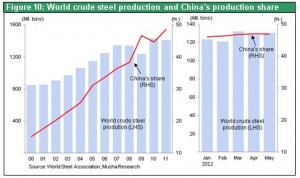

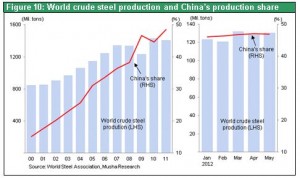

Changes are taking place in many of the factors that supported China’s investment-based economy. A real estate bubble has emerged. Global economic growth is slowing. China’s role as the world’s factory has passed its peak. And the country has excess output capacity as its share of global manufacturing declines. Crude steel production exemplifies these changes. As you can see in Figure 10, China’s share of global crude steel output is about to stop climbing as China’s economic growth slows.

Consequently, there is an urgent need for China to alter the structure of its growth. The country must switch from investments to consumption as the primary driver of growth. To accomplish this switch, China needs to increase consumption by raising wages in line with productivity. In addition, there must be a transfer of income from sectors with high productivity to low-productivity sectors like agriculture and services. Moreover, this transfer must be supported by inflation that boosts prices of agricultural products and various services. Unfortunately, China is making no progress with this transfer. Along China’s Pacific coast, a shortage of agricultural workers is causing wages to rise in this sector. Although China has a surplus of agricultural workers, limitations on the relocation of these workers allow this labor shortage and accompanying income differential to persist. The income gap between cities and agricultural villages, skilled and unskilled laborers, and other sectors in China is not decreasing. As long as factors like these restrict the allocation of labor, there will be no improvement in China’s ability to increase consumption.

Figure 10: World crude steel production and China’s production share

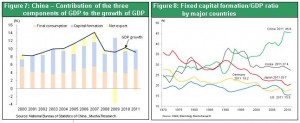

Japan’s 1960 turning point and correction of income inequalities led to consumption-driven growth

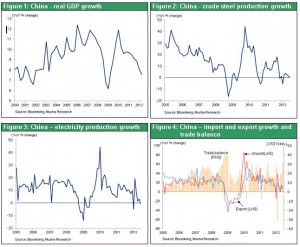

Japan confronted the same challenges during its fast-growth years. But there are several critical differences between the situation in Japan at that time and in China today. First, Japan’s highest capital formation/GDP ratio was nearly 10percentage points below the current ratio in China. A much smaller adjustment was required in Japan as a result. Second, Japan has a more flexible labor market. There was a smooth process of eliminating surplus agricultural workers that in turn caused wages to climb. Third, Japan simultaneously lowered the capital formation/GDP ratio and increased labor’s share of income. As a result, there was a smooth transition from investments to consumption. Fourth, domestic demand was increasing in Japan along with its population.

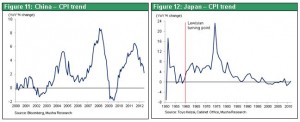

Japan passed the Lewisian turning point in 1960 as a major shift occurred in the allocation structure of the economy. Once there was no longer any surplus of agricultural workers in the 1960s, Japan’s labor market tightened (more than one job opening for each job seeker) and wages rose at a double-digit pace. Since then, the increase in Japan’s consumer price index was consistently above 5% and there was a large increase in labor’s share of income. Income inequalities quickly disappeared and there was rapid growth in domestic demand. The result was economic growth centered on consumption. However, these types of changes are not occurring in China today. The consumer price index had started to increase but inflation has once again dropped to the 2% level. Furthermore, there is no progress at all regarding the elimination of income gaps. These points demonstrate that China has not yet passed the Lewisian turning point. As a result, China will probably have to overcome significant challenges in order to achieve the necessary corrections in its economy.

Figure 11: China - CPI trend

Figure 12: Japan - CPI trend