Progress in Europe and elimination of a nightmare scenario for the debt crisis point to a resurgence in risk-taking

An exit from Europe’s problems is in sight. For the time being, there is no longer any possibility of a euro collapse triggered by the withdrawal of Greece as well as Spain and Italy. Basic agreement was reached to create a Banking Union, a single supervisory body to oversee banks and to inject funds into banks directly from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Furthermore, ESM and other funds will be used to buy the bonds of Spain, Italy and other countries. Everything needed for a safety net is now in place. As a result, we are much more likely to see a resolution to the eurozone crisis that brings countries closer together rather than farther apart.

This accomplishment was made possible by three areas of progress since 2011 that many commentators have overlooked. The first is the formation of a consensus to preserve the euro. One year ago, the majority of politicians and voters in Germany apparently believed that “it would be better to allow the euro to collapse rather than spend German taxpayers’ money to save Greece, which is a lazy country.” Furthermore, many people thought that southern European countries in need of aid would probably abandon the euro instead of restructure their economies and rebuild public-sector finances. However, once the magnitude of the consequences of abandoning the euro became clear, the populist position of breaking up the eurozone between north and south rapidly lost support. Southern European countries (Italy, Spain, Greece) secured the political support for enacting the necessary reforms and financial measures. In Germany, there is now political support for helping cover the cost of this aid.

The second area of progress is the establishment of a safety net. One key component is long-term refinancing operations (LTRO) by the European Central Bank (ECB) to supply liquidity. The formation of an entity to facilitate the use of public-sector funds from the ESM and other sources is another element of this safety net. At the most recent EU summit, leaders agreed on a method to utilize these safety net measures effectively.

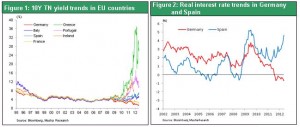

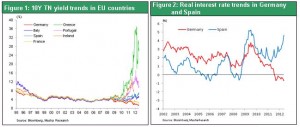

Figure 1: 10Y TN yield trends in EU countries

Figure 2: Real interest rate trends in Germany and Spain

The third area of progress is the revitalization of markets, which has created the proper way to solve Europe’s problems and shut out populist beliefs. Up to 2008, under the EU’s unified interest rates, southern European countries had advantage to enjoy low effective interest rates. This made possible for funds to continue flowing to these countries (see Figure 2) and was an obstacle to reforms. Furthermore, Germany would probably not have extended assistance to southern European countries without the surge in government bond interest rates and drop in prices (because this would lead directly to a severe financial crisis in Germany and France). Financial markets issued the correct warning and Europe has navigated the narrow path that will allow the euro to survive.

In this respect, Germany has acted properly while constantly refusing to permit the issuance of joint euro-bonds with easy terms. Issuing these bonds without strict conditions would bring the eurozone back to the pre-2008 days of a unified long-term interest rate. This must not happen because it would prompt investors to shift funds to financially troubled countries, thereby taking away any incentive for these countries to enact reforms. There is only one solution: using reforms along with efficient labor and capital markets to make these countries better able to maintain long-term growth.

Impediments to a summer rally: the fiscal cliff, slowing growth in China, resource-rich countries and the European economy

Investors no longer need to worry about a nightmare scenario unfolding in Europe. That means they will probably start closing down their portfolios based on extremely pessimistic beliefs. However, the outlook is not entirely positive for the following three reasons. First, is the U.S. fiscal cliff. Bush-era tax reductions and tax cuts that followed the Lehman shock are due to expire at the end of December. Furthermore, the across-the-board spending cuts approved by the U.S. Congress in 2011 will become effective in 2013 (if there are no budget reforms). According to estimates of the Congressional Budget Office and other sources, these cuts will lower annual U.S. GDP growth by about four percentage points. It is difficult to believe that the Obama administration and Congress would stand by and let this crime take place. I believe there is no doubt that the U.S. will extend both the tax and spending cuts. However, political bickering involving this issue may produce another uproar about increasing the debt ceiling just as we saw in the summer of 2011. This will constantly be a major factor that holds down stock prices.

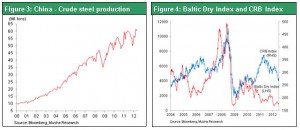

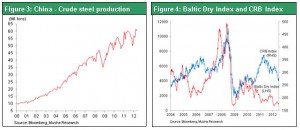

The second reason is concerns about the myth that China’s economy will keep expanding year after year. In 2010, China’s fixed capital formation to GDP ratio was 46%. No other country has ever achieved a ratio this high. Investments have surpassed consumption in China every year since 2005 at an accelerating pace. But this cannot continue. The same situation existed in Japan and South Korea at one time. Shifting substantial resources to an economy fueled by investments and exports can temporarily boost the economic growth rate (supply of goods). On the other hand, these same measures make it difficult to achieve a soft landing that results in sustained growth in demand along with a higher standard of living. Falling land prices lowered gains on sales of land, the primary source of revenue for local governments in China. At the same time, the country began to struggle with a surplus of output capacity because its share of global production has passed the peak. By reducing the demand for resources, slowing economic growth in China is also influencing the economies of Australia, Brazil and other resource-producing countries.

The third negative factor involving the outlook is the European economy. Even if the debt crisis can be brought under control, Europe’s economic growth rate will probably remain near a recessionary level for the foreseeable future. I do not expect to see increasing growth in Germany return Europe to economic expansion for some time.

Figure 3: China - Crude steel production

Figure 4: Baltic Dry Index and CRB Index

Japanese stocks may jump-start a rally

With problems in the United States, China, Europe and resource-producing countries, Japan may very well become the starting point for risk-taking. Japanese stocks have dropped 20% since the euro crisis flared up again last May, a bigger decline than in any other major country. This downturn wiped out the entire gain that Japanese stocks had made in 2012. The cause is a conditioned reflex of global investors since the collapse of Lehman brothers: To avoid risk, buy the yen and sell Japanese stocks. But in June, Japanese stocks began to bounce back from this unjustified downturn. I believe there are several important reasons to expect a rally in Japanese stocks other than merely a correction from a decline that went too far.

A reevaluation of Japan’s political power is the first reason. A consumption tax hike was approved by the Lower House with the support of the ruling and opposition parties. Reforming taxes and the social security system at once will probably focus investor’s attention on the resurgence of Japan’s ability to enact political initiatives (the return of a “Japan that can make decisions). In addition, the exit is near for Ichiro Ozawa, who has been a disruptive force in Japan’s politics for the last 20 years. Moreover, people are beginning to take another look at the political power of Japan, which avoided a plunge into a deep recession after its asset bubble burst. For instance, Paul Krugman has started criticizing himself rather than Japan. Increasing pressure on the Bank of Japan to end deflation is another positive development.

Second is the renewed respect that Japanese companies are receiving for several reasons: (1) the global expansion of Japanese companies (manufacturers and service providers) as the yen remains extremely strong, (2) the strength of high-tech market sectors (high-tech niche categories that have not become commodities) where Japanese companies are at the leading edge of progress, (3) the overwhelming competitive edge of Japanese product in terms of their quality, and (4) the steep recovery in earnings of Japanese companies despite the yen’s strength, natural disasters and economic problems worldwide.

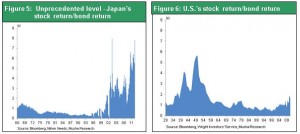

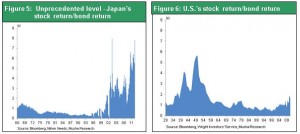

The third and most important reason is the undervaluation of Japanese stocks, which has reached an unprecedented level. No other country’s stocks are undervalued to this degree. A comparison of stock and bond returns, which is the simplest valuation metric, is shown in Figures 5 and 6. As you can see, Japan’s stock return is now at all-time high of 8 times the return on bonds. This is a positive signal of the same magnitude as the negative signal at the peak of Japan’s asset bubble when this multiple was about one-fourth. In the United States, this multiple approached the current level in Japan only in 1949 when it was about 5 times. This was the starting point of a powerful rally in U.S. stocks.

Figure 5: Unprecedented level - Japan’s stock return/bond return

Figure 6: US’s stock return/bond return

The revival of the “equity boom” and demise of the “bond mania” will start in Japan

Interest rates have fallen too far in the United States, Germany, United Kingdom and other major countries. Many people believe that a bubble has formed. Once investors are convinced that economies are recovering from the Lehman shock and the crisis in Europe has been resolved, they will be forced to restructure their portfolios to shift from risk avoidance to risk taking. Confidence that the risk of a depression has ended and sustained economic growth has started will reverse the “flight to quality.” The start of this reversal will signal the beginning of a massive movement of capital. During the three decades since 1980, an unprecedented decline from 15% to less than 2% has taken place in the U.S. long-term interest rate. The result is a bond market bubble on a scale never seen before. But the long upturn in bond prices is probably over. If indeed this “age of bonds” has come to an end, the “age of stocks” will be next. The period from 2000 to 2009 was the worst decade ever for stocks. Now this age has most likely ended. Due to undervalued stock prices, companies are altering their financial activities by using bonds instead of stocks to procure funds. In other words, many companies are issuing bonds to raise funds and then using the proceeds to buy back their own stock. This explains why some people are saying that a bull market is about to begin in the US and the world. I am in fundamental agreement with this view.

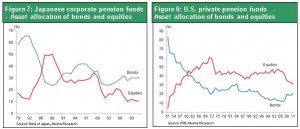

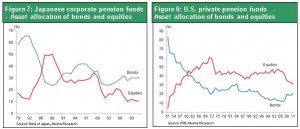

Nevertheless, there is widespread belief that the global stock market will not advance to this “age of the bull” so easily. The reasons are changes in government policies and expectations for a deterioration in supply-demand dynamics. A large number of investors and financial institutions suffered enormous losses because of the financial crisis. As a result, governments have been imposing restrictions such as Basel III on the use of funds and risk-taking activities. Enacting these policies creates long-term distortions in the supply and demand for stocks by making pension funds and other investors sell stocks. The resulting weakness in the balance between supply and demand could be the greatest obstacle to the beginning of a bull market. In fact, as Figure 8 shows, although stocks have decreased as a percentage of private-sector pension plan assets in the US, the percentage is still much higher than for bonds.

Consequently, there is still much more room for a further decline in the weighting of stocks.

This story does not apply at all to Japanese stocks. As you can see in Figure 7, stocks are only 15% of pension plan assets, half the U.S. level. This is only about one-fourth the percentage for stocks in 1989, demonstrating how much stocks are underweighted. The weighting of stocks has dropped as well for household savings, insurance companies, banks and all other categories of investors. Japan clearly has an extreme overweighting of bonds and underweighting of stocks. The extreme undervaluation of Japanese stocks can therefore be regarded as the result of worsening supply-demand dynamics caused by the long-term reduction in the weighting of stocks by Japanese investors.

Japan’s weighting of stock investments, which is very small based on both international comparisons and historical comparison in Japan, is likely to be a major contributing factor to an improvement in the supply-demand dynamics for Japanese stocks coming years. The age of the strong yen, deflation, and low stock prices and interest rates may be over. If this is true, all investors in Japan will be forced to make a significant change in their portfolios to eliminate the current extreme overweighting of bonds. The big improvement in the balance between the supply and demand for stocks will probably trigger a sharp increase in the prices of Japanese stocks.

The prolonged strength of the yen appears to be nearing its end. When will Japanese investors no longer base their decisions solely on deflation and an aversion to risk? Investors around the world have started to closely watch Japanese investors’ attitude and stock market to see when this change happens.

Japan is one of the few remaining virgin territories among the world’s financial markets. This is why I strongly recommend that when investors decide to resume risk taking, they should start by purchasing Japanese stocks.

Figure 7: Japanese corporate pension funds - Asset allocation of bonds and equities

Figure 8: US private pension funds - Asset allocation of bonds and equities

The third area of progress is the revitalization of markets, which has created the proper way to solve Europe’s problems and shut out populist beliefs. Up to 2008, under the EU’s unified interest rates, southern European countries had advantage to enjoy low effective interest rates. This made possible for funds to continue flowing to these countries (see Figure 2) and was an obstacle to reforms. Furthermore, Germany would probably not have extended assistance to southern European countries without the surge in government bond interest rates and drop in prices (because this would lead directly to a severe financial crisis in Germany and France). Financial markets issued the correct warning and Europe has navigated the narrow path that will allow the euro to survive.

In this respect, Germany has acted properly while constantly refusing to permit the issuance of joint euro-bonds with easy terms. Issuing these bonds without strict conditions would bring the eurozone back to the pre-2008 days of a unified long-term interest rate. This must not happen because it would prompt investors to shift funds to financially troubled countries, thereby taking away any incentive for these countries to enact reforms. There is only one solution: using reforms along with efficient labor and capital markets to make these countries better able to maintain long-term growth.

The third area of progress is the revitalization of markets, which has created the proper way to solve Europe’s problems and shut out populist beliefs. Up to 2008, under the EU’s unified interest rates, southern European countries had advantage to enjoy low effective interest rates. This made possible for funds to continue flowing to these countries (see Figure 2) and was an obstacle to reforms. Furthermore, Germany would probably not have extended assistance to southern European countries without the surge in government bond interest rates and drop in prices (because this would lead directly to a severe financial crisis in Germany and France). Financial markets issued the correct warning and Europe has navigated the narrow path that will allow the euro to survive.

In this respect, Germany has acted properly while constantly refusing to permit the issuance of joint euro-bonds with easy terms. Issuing these bonds without strict conditions would bring the eurozone back to the pre-2008 days of a unified long-term interest rate. This must not happen because it would prompt investors to shift funds to financially troubled countries, thereby taking away any incentive for these countries to enact reforms. There is only one solution: using reforms along with efficient labor and capital markets to make these countries better able to maintain long-term growth.