Apr 11, 2012

Strategy Bulletin Vol.67

No need to worry about the bottom falling out of the JGB market

World’s lowest interest payments as percentage of GDP

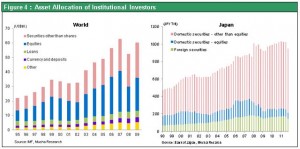

The consumption tax hike proposed by Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda has made the Japanese government’s fiscal problems the focus of discussions about the nation’s economy and government policies. There is no doubt that excessive public-sector debt will create enormous challenges for Japan in the future. On the other hand, inadequate demand is the greatest problem for the Japanese economy today. Moreover, budget deficits are definitely performing a beneficial role by using excess capital to generate demand. The Japanese economy would probably have become mired in a deflationary spiral if the government had cut expenditures while the country had massive excesses of labor and capital. To cut the budget deficit, Japan’s highest priority must be to restore economic growth so that public-sector spending is no longer needed to create demand. Massive public-sector debt is oppressive for companies, individuals and all other components of economic activity. But one of mankind’s most important discoveries is that a suitable amount of debt (credit) can fuel economic growth. The question is where to draw the line between suitable and excessive levels of debt. Unfortunately, the answer can be determined only afterward. In his memoir The Age of Turbulence, former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan noted that banks needed a capital ratio of about 40% to be viewed as financially sound during the Civil War. Today, a ratio of 10% is sufficient. Consequently, we must realize that the amount of debt that is suitable varies significantly depending on the period of history and economic conditions. Japan’s government debt is 200% of its GDP, the highest in the world. But at only about 1%, the long-term interest rate in Japan is the lowest in the world. Thanks to this low interest rate, the Japanese government’s interest payments are only 1% of GDP, again the lowest in the world. Greece faced insolvency even though its debt ratio is lower than in Japan. The cause was a sharp upturn in the long-term interest rate in Greece. From only 4% prior to the debt crisis a few years ago, the long-term interest rate in Greece surged to 10% once the crisis began and then to 20%. Rapidly rising interest rates can obviously be viewed as a requirement for transforming fears of a country’s insolvency into reality. Figure 1: Comparison among the major countries; Government gross debt ratio to nominal GDP Figure 2: Comparison among the major countries; Government’s interest payment ratio to nominal GDP

How does capital move when government bond prices plummet?

This discussion leads to the question of whether or not Japan could face an insolvency crisis caused by a sharp upturn in interest rates, as we have just witnessed in Greece. I believe that this is very unlikely to happen. Interest rates rise quickly when there is a sudden shift of capital as investors sell off government bonds and purchase other assets. There is always another asset class to replace government bonds. As the European debt crisis unfolded, investors sold Greek and Italian government bonds and bought German government bonds. Shortages of funds in Greece and other southern European countries caused their economies to weaken. Governments responded with restructuring, budget cuts and other measures. At the same time, Germany benefited from an investment boom as its interest rates fell to an unprecedented low.

A drop in JGB prices would weaken the yen and boost stock prices

If investors sold off Japanese government bonds, there would be only three alternatives for reinvesting these funds. First is cash, which has a lower risk than the bonds. Second is corporate bonds, mortgage bonds, stocks, real estate and other private-sector assets, all of which have a higher risk. Third is overseas investments. Cash is inconceivable as an alternative because the Bank of Japan would undoubtedly respond to the crisis of falling bond prices by monetizing the debt. During a crisis sparked by a loss of confidence in Japan, such as a plunge in the JGB market, investors would regard government bonds and the currency (Japanese yen) as even more equivalent as debt obligations of the Japanese government. Clearly, cash would not be attractive as a safe haven for investors in this environment. As a result, if the bottom drops out of the JGB market, investors will have to choose either the second option, moving funds to stocks and other high-risk private-sector assets, or third option, moving funds to investments in other countries. Therefore, there is a high probability that a plunge in the JGB market would be accompanied by a stock market rally or a downturn in the yen.

A correction in Japan’s abnormal allocation of assets is inevitable

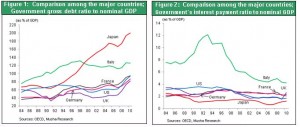

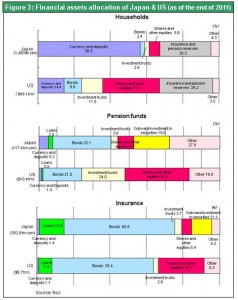

Many investors in Japan hold huge quantities of Japanese government bonds even amid fears of a sharp drop in the prices of these bonds. In Japan, stocks account for 6% and bonds and cash for 59% of financial assets held by households. In the United States, stocks are 32% of household financial assets and bonds and cash are only 24%. At pension funds in Japan, Japanese stocks are 9% of holdings and bonds and cash are 37%. But stocks are 36% of U.S. pension fund portfolios and bonds and cash are 23%. At insurance companies, these ratios are 5% for Japanese stocks and 62% for bonds and cash in Japan and 25% for stocks and 56% for bonds and cash in the United States. This unusually high bond portfolio weighting , particularly that of JGBs, was appropriate only during the abnormal economic environment of a strong yen, deflation and extremely low interest rates that characterized Japan’s “lost 20 years.” However, a plunge in the JGB market would signal the end of this abnormal environment. Stock prices would begin to climb and the yen would weaken. Wages that have been falling steadily for 20 years would turn upward as a result and Japanese products would become more competitive. Stock and real estate prices would both increase. Consequently, even if JGB prices plunge, there may be a bureaucratic crisis but there will be no crisis for the Japanese economy. Figure 3:Financial assets allocation of Japan & US (as of the end of 2011)  Figure 4:Asset Allocation of Institutional Investors

Figure 4:Asset Allocation of Institutional Investors