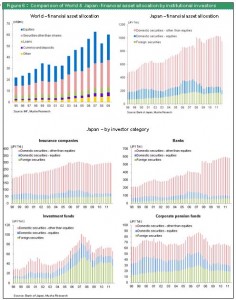

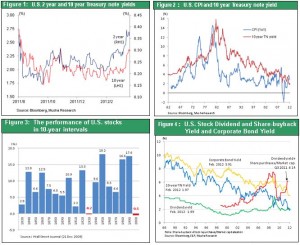

Bond prices have been falling since February as U.S. stocks continue to rally

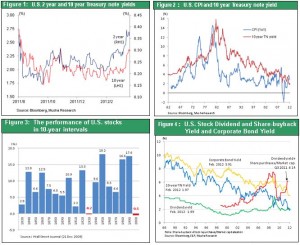

Investors have started to sell off substantial holdings of bonds as the sustained upturn in U.S. stocks continues. After falling to a low of 1.82% on January 31, the 10-year Treasury note yield has rebounded to 2.38% (March 19). The 2-year yield reached a low of 0.21% on January 27 and subsequently rose to 0.41% (March 14). An increasing number of investors believe that long-term interest rates bottomed out early in 2012 (Figure 1). Investors are confident that there is no longer any risk of a depression and that the economic recovery will continue. As a result, we are probably seeing the start of a major shift in capital as investors reverse their previous “flight-to-quality” stance. A decline in U.S. long-term interest rates of historic proportions occurred during the past three decades as rates fell from 15% to less than 2% (Figure 2). It was a bull market for bonds on a scale never seen before. But this rally is probably over. If the bond era has indeed ended, the era of stocks will be next. Figure 3 shows the performance of U.S. stocks in 10-year intervals. Stock returns in the 10-year period from 2000 to 2009 were the worst ever, but this difficult phase has probably reached its end.

Figure 1: U.S. 2 year and 10 year Treasury note yields

Figure 2: U.S. CPI and 10 year Treasury note yield

Figure 3: The performance of U.S. stocks in 10-year intervals

Figure 4: U.S. Stock Dividend and Share-buyback Yield and Corporate Bond Yield

Companies brought down interest rates by issuing bonds and repurchasing stock

The emergence of a substantial shift of capital in the United States can be regarded as a correction to eliminate the unusually high risk premium. The gap between the return on risk-free assets (10-year Treasury note yield) and the return on assets with risk (usually regarded as the earnings yield for stocks) has started to narrow as investors move funds from Treasuries to stocks. Companies are the primary force behind this shift. Even though companies hold unprecedented amounts of idle funds, the volume of corporate bond issues grew to an all-time high while interest rates fell to an all-time low. These funds will be used for repurchasing stock. For instance, Apple has a massive cash stockpile of about $100 billion. The company announced on March 19 that it will return $45 billion to shareholders (including a $10 billion share repurchasing program) over the next three years. Apple’s decision is a prime example of how companies are now investing their excess funds in stocks. Initiatives like this by companies to lower the risk premium will be a major source of energy for the U.S. stock market. Overall, these activities will facilitate the recycling of funds earned by highly profitable companies like Apple back to the economy.

Japan during the past decade has been the exact opposite of this situation. Companies in Japan accumulated large amounts of cash due to strong earnings. However, there was absolutely no decline in Japan’s enormous risk premium because companies refused to buy back their stock or purchase assets with risk.

As I have been saying for a long time, a correction will occur at some time to eliminate the unusually strong aversion to risk and the high risk premium that accompanies this sentiment. There are only three ways to achieve this correction: (1) a plunge in earnings and dividends sparked by a severe economic downturn; (2) a sharp rise in interest rates sparked by inflation and a weaker currency; and (3) a powerful stock market rally. In the United States, a stock market rally is very likely to be how the risk premium correction takes place.

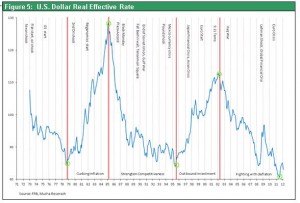

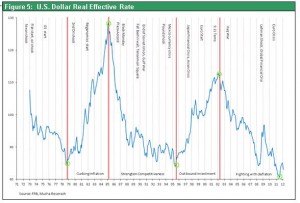

The shift in the dollar’s long-term direction

A healthy economy, rising interest rates and a stock market rally will trigger a big turnaround for the U.S. dollar. Figure 5 shows the long-term cycle of the dollar. As you can see, the 10-year downturn of the dollar between 2002 and 2011 has come to an end.

Figure 5: U.S. Dollar Real Effective Rate

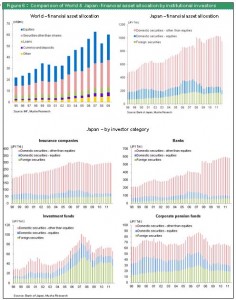

Japan too will move from bonds to stocks

In Japan, the weakness of interest rate arbitrage has prevented interest rates from climbing as much as in the United States. The long-term interest rate in Japan is up by only 0.1% from the low of 0.95% for the past year. Furthermore, the volume of corporate bond issues and share repurchases is small. Consequently, Japan lacks the energy to trigger interest rate arbitrage. However, as you can see in Figure 6, Japanese investors are extremely reluctant to take on any exposure to risk. This is evident in their large holdings of Japanese government bonds and the very low portfolio weighting of stocks and other assets with risk. Due to this situation, once funds began to flow away from risk-free assets (government bonds), investors should expect to see a powerful stock market rally along with a decline in the yen’s value.

Figure 6:Comparison of World & Japan - financial asset allocation by institutional investors