The BOJ’s “about face” is a river of no return

On February 14, the Bank of Japan announced an increase in asset purchases and a goal for inflation. This easy-money stance is very likely to bring an end to the ongoing period of deflation linked to the yen’s strength. Why did the BOJ decide to make an abrupt shift in its previous policy? The first reason is that the BOJ could no longer stand being the target of intense criticism. Samsung recently announced record earnings. At the same time, Panasonic, Sony and Sharp are all suffering from enormous losses. Apparently, these Japanese companies can no longer cope with the strength of the yen, which has appreciated 50% against the Korean won since the Subprime financial crisis. The BOJ can no longer ignore the doubt regarding whether the bank is really doing everything possible to respond to this damage to Japanese industry. The second reason is that a policy turnaround was the BOJ’s only option now that U.S. quantitative easing has succeeded in preventing deflation, fueling a stock market rally and improving sentiment about the economy.

By establishing an inflation goal just as the Fed did, the BOJ has assumed responsibility for reaching this target. The Fed believes that inflation can be controlled with monetary policy. But the BOJ has been stubbornly embracing its long-standing stance that “monetary policy alone cannot conquer deflation because supply-demand gaps are the fundamental cause of deflation.” This is why some people view the BOJ’s policy shift as a superficial pretention. However, now that a goal has been established, the BOJ will have to provide reasons for its failure if the goal is not achieved. Moreover, if endaka deflation continues, the BOJ will be forced to respond on an unlimited scale that includes more asset purchases, which would make the BOJ’s balance sheet even larger. The widespread conviction that the BOJ has changed and will have to change even more is fueling both the yen’s strength and the stock market rally.

The clear gap between the timing for the end of record-low U.S. and Japanese interest rates

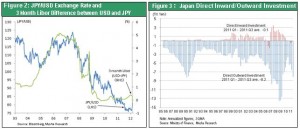

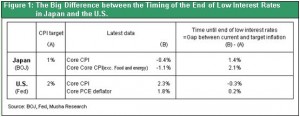

The BOJ’s February 14 announcement of an inflation target, following the Fed’s announcement on January 25, underscored the significant gap between U.S. and Japanese monetary policies. Figure 1 shows the difference between central bank inflation targets and current inflation in the U.S. and Japan.

As you can see, there is a big gap between Japan’s difference of 1.4%-2.1% and the U.S. difference of 0.2%-0.3%. Interest rates will have to stay at almost zero until the inflation goals are reached. Consequently, Japan will have to hold down interest rates for a long time. However, since the U.S. has is already close to its inflation target, interest rates can start rising soon. But the Fed is responsible for jobs as well as inflation. As a result, in response to the slow speed of the recovery in jobs, Chairman Ben Bernanke has stated that interest rates will stay unusually low until late in 2014. Nevertheless, since inflation is already above the target, we may see an earlier end to low interest rates if stock prices, economic growth and employment all recover faster than the Fed currently foresees.

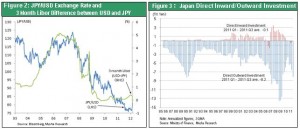

These differences in U.S. and Japanese monetary policy will probably lead to a significant decline in the yen’s value due to the gaps between the expected timing of the end of low interest rates and short-term interest rates in these two countries. The yen/dollar rate generally mirrors the difference between U.S. and Japanese short-term interest rates. As you can see in Figure 2, this gap stopped narrowing in the middle of 2011 and has been slowly increasing since then. A significant difference now exists between the U.S. and Japan in the time needed (B-A) until interest rates can be allowed to start climbing. This timing difference is very likely to further widen the short-term interest rate gap, which will make the switch to a stronger dollar even more pronounced.

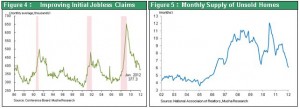

We are also seeing a substantial shift in the yen’s supply-demand dynamics. Japan had a trade deficit in 2011 for the first time in 31 years and the current account surplus fell below \10 trillion. At the same time, Japan’s direct overseas investments surged. Moreover, Japanese financial institutions purchased large volumes of assets in response to the European financial crisis. As a result, capital outflows from Japan of almost \10-20 trillion are expected in 2012 for direct overseas investments. Against this backdrop, there is growing talk about the possibility of a sharp drop of the Japanese government bonds because of the crisis in Greece. Japanese insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds and other large institutions hold a large percentage of JGBs. Once these institutions see signs of an end to deflation and an upturn in interest rates, they will have to shift their holdings to higher-return assets such as stocks, overseas assets and real estate. Making this shift will accelerate the flow of portfolio investments to overseas assets. Since 2008, Japan’s financial markets have been defined by an extreme aversion to risk. Investors believed that a strong yen would cause deflation that would produce a JGB bubble (extremely low yields). But investors must now make a fundamental shift in their stance. This is why there is a high probability that the yen’s extremely long period of strength has finally come to an end.

A big turnaround in the endaka/kabuyasu trend triggered by (a) a resurging U.S. economy and (b) the BOJ’s about face

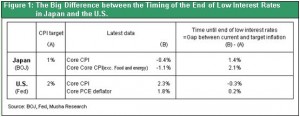

The fundamental shift I just described is obviously based on the assumption of a steady recovery of the U.S. economy, the primary source of growth for the global economy. Corporate earnings have been a bright spot of the U.S. economy for some time. But now, marked improvements are also taking place in two sectors that have been serious problems: employment and housing. In January, the United States added 240,000 jobs and the unemployment rate fell to 8.3% from 8.5% in December. Initial unemployment benefit applications fell to 350,000 in February. This is the level at which the rate of job growth gained momentum in the past. A sharp drop in inventories of homes for sale is more good news. These inventories have been consistently holding down prices of homes, which were already remarkably undervalued in relation to affordability. Another positive sign is the rising rate of inflation (U.S. core CPI was 1.1% in 1Q and 2.2% in 4Q of 2011 and 2.3% in January 2012). This shows that wages are rising, which means households have more purchasing power. In addition, loans to companies have been increasing and consumer loans have started to climb, too. All these trends indicate that the severe downturn that started in 2009 has finally set the stage for a prolonged recovery of the U.S. economy.

The end of the yen’s strength also signifies the end of deflation

Pessimists who expected the yen to remain strong quickly shifted their stance to “worries about a bad enyasu” once the yen began to weaken. Nikkei Business magazine printed an article in its February 27, 2012 issue with the following off-target position: “The BOJ Steps on the Land Mine of a Plunge in the Yen’s Value.” But there can be no “bad enyasu” in the Japan of today. Only benefits can come from a weaker yen. Precisely the opposite situation, a stronger yen and deflation, was what was evil. Deflation punishes borrowers and risk-takers. Deflation also destroys the spirit of capitalism and investors’ animal spirits. Furthermore, a deflationary environment makes it impossible to use inflation to offset differences in rates at which productivity improves. The result is serious pain for low productivity growth domestic demand sector. In other words, income distribution is distorted and gaps become even greater. Furthermore, government payments are not adjusted downward with deflation. Relative incomes of government employees, people receiving government pensions and others with income outside the business sector climb as a result. This makes income distribution even more unfair. A negative cycle driven by a stronger yen and deflation was the defining characteristic of Japan’s “lost two decades.” Ending this cycle is very likely to bring about a fundamental shift in the appearance of Japan’s economy and its markets.

For more information about this subject, please see the three-part series discussing perspectives on deflation in Japan (link below) and the book The End of the Lost 20 Years (2011, Toyo Keizai) by Ryoji Musha.

Mar. 5, 2010

(Vol.289) Perspectives on deflation in Japan ? 3

Lessons for the world from Japan’s experience with deflation~Creating demand is the most pressing issue; consumption rather than saving is a virtue~

Feb. 26, 2010

(Vol.288) Perspectives on deflation in Japan ? 2

How the “lost 20 years” made Japan even stronger

Feb. 19, 2010

(Vol.287) Perspectives on deflation in Japan ? 1

The strong yen is the primary reason for deflation, which is the root cause of Japan’s economic stagnation

As you can see, there is a big gap between Japan’s difference of 1.4%-2.1% and the U.S. difference of 0.2%-0.3%. Interest rates will have to stay at almost zero until the inflation goals are reached. Consequently, Japan will have to hold down interest rates for a long time. However, since the U.S. has is already close to its inflation target, interest rates can start rising soon. But the Fed is responsible for jobs as well as inflation. As a result, in response to the slow speed of the recovery in jobs, Chairman Ben Bernanke has stated that interest rates will stay unusually low until late in 2014. Nevertheless, since inflation is already above the target, we may see an earlier end to low interest rates if stock prices, economic growth and employment all recover faster than the Fed currently foresees.

These differences in U.S. and Japanese monetary policy will probably lead to a significant decline in the yen’s value due to the gaps between the expected timing of the end of low interest rates and short-term interest rates in these two countries. The yen/dollar rate generally mirrors the difference between U.S. and Japanese short-term interest rates. As you can see in Figure 2, this gap stopped narrowing in the middle of 2011 and has been slowly increasing since then. A significant difference now exists between the U.S. and Japan in the time needed (B-A) until interest rates can be allowed to start climbing. This timing difference is very likely to further widen the short-term interest rate gap, which will make the switch to a stronger dollar even more pronounced.

We are also seeing a substantial shift in the yen’s supply-demand dynamics. Japan had a trade deficit in 2011 for the first time in 31 years and the current account surplus fell below \10 trillion. At the same time, Japan’s direct overseas investments surged. Moreover, Japanese financial institutions purchased large volumes of assets in response to the European financial crisis. As a result, capital outflows from Japan of almost \10-20 trillion are expected in 2012 for direct overseas investments. Against this backdrop, there is growing talk about the possibility of a sharp drop of the Japanese government bonds because of the crisis in Greece. Japanese insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds and other large institutions hold a large percentage of JGBs. Once these institutions see signs of an end to deflation and an upturn in interest rates, they will have to shift their holdings to higher-return assets such as stocks, overseas assets and real estate. Making this shift will accelerate the flow of portfolio investments to overseas assets. Since 2008, Japan’s financial markets have been defined by an extreme aversion to risk. Investors believed that a strong yen would cause deflation that would produce a JGB bubble (extremely low yields). But investors must now make a fundamental shift in their stance. This is why there is a high probability that the yen’s extremely long period of strength has finally come to an end.

As you can see, there is a big gap between Japan’s difference of 1.4%-2.1% and the U.S. difference of 0.2%-0.3%. Interest rates will have to stay at almost zero until the inflation goals are reached. Consequently, Japan will have to hold down interest rates for a long time. However, since the U.S. has is already close to its inflation target, interest rates can start rising soon. But the Fed is responsible for jobs as well as inflation. As a result, in response to the slow speed of the recovery in jobs, Chairman Ben Bernanke has stated that interest rates will stay unusually low until late in 2014. Nevertheless, since inflation is already above the target, we may see an earlier end to low interest rates if stock prices, economic growth and employment all recover faster than the Fed currently foresees.

These differences in U.S. and Japanese monetary policy will probably lead to a significant decline in the yen’s value due to the gaps between the expected timing of the end of low interest rates and short-term interest rates in these two countries. The yen/dollar rate generally mirrors the difference between U.S. and Japanese short-term interest rates. As you can see in Figure 2, this gap stopped narrowing in the middle of 2011 and has been slowly increasing since then. A significant difference now exists between the U.S. and Japan in the time needed (B-A) until interest rates can be allowed to start climbing. This timing difference is very likely to further widen the short-term interest rate gap, which will make the switch to a stronger dollar even more pronounced.

We are also seeing a substantial shift in the yen’s supply-demand dynamics. Japan had a trade deficit in 2011 for the first time in 31 years and the current account surplus fell below \10 trillion. At the same time, Japan’s direct overseas investments surged. Moreover, Japanese financial institutions purchased large volumes of assets in response to the European financial crisis. As a result, capital outflows from Japan of almost \10-20 trillion are expected in 2012 for direct overseas investments. Against this backdrop, there is growing talk about the possibility of a sharp drop of the Japanese government bonds because of the crisis in Greece. Japanese insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds and other large institutions hold a large percentage of JGBs. Once these institutions see signs of an end to deflation and an upturn in interest rates, they will have to shift their holdings to higher-return assets such as stocks, overseas assets and real estate. Making this shift will accelerate the flow of portfolio investments to overseas assets. Since 2008, Japan’s financial markets have been defined by an extreme aversion to risk. Investors believed that a strong yen would cause deflation that would produce a JGB bubble (extremely low yields). But investors must now make a fundamental shift in their stance. This is why there is a high probability that the yen’s extremely long period of strength has finally come to an end.