The stock market’s rules have changed from risk on/off to long-term value

The Dow Jones Industrial Average has climbed to a new high after the Lehman Brothers collapse as employment, orders for durable goods and other U.S. economic indicators rebound. These statistics are confirming the sustained upswing in stock prices in the wake of the Lehman shock. Events strongly indicate that the large volume of idle funds in the world has finally shifted to stock investments. We are witnessing the start of a change in the rules that govern the “stock market game.” Value stocks are performing well. Trading volume is low. Volatility has fallen sharply. Changes like these explain why we no longer see short-term speculation that chases short-term returns by inciting volatility and then taking advantage of big price swings. If this is true, the new rules may be the start of a long-term stock market trend rather than merely part of a risk-on/risk-off cycle. Over the past several years, value investing that targets undervalued stocks has not done well due to the challenge posed by short-term stock price volatility. But the stock market is now entering a different phase.

The unprecedented yield gap can no longer be ignored

- 2% long-term interest rate vs. 6% yield (dividends + buybacks)

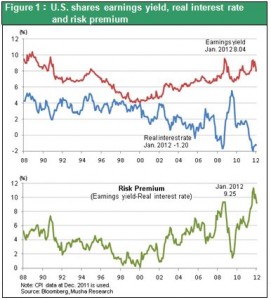

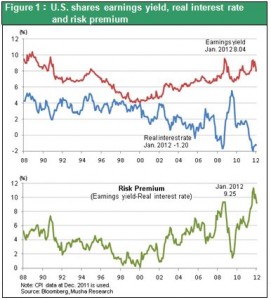

The result is the growth of the return gap (risk premium) to an unprecedented scale. The enormous risk premium (which signifies that stocks are undervalued) shown in Figure 1 can be interpreted as a reflection of the outlook of investors for a dramatic economic downturn. Investors were not enticed regardless of how high short-term returns became because they believed a severe economic downturn could wipe out corporate earnings. But even so, there is a limit to this stance. Stocks have a 2% dividend yield and companies are buying back stock at an annual rate of 4% in relation to their stock prices. That means companies are returning cash to investors at an annual rate of 6% of their stock prices. At the same time, real interest rates on government bonds are negative.

Figure 2 shows the cash return on U.S. stocks, which is the sum of dividends and buybacks divided by market capitalization. The dividend-buyback yield has climbed to an all-time high, excluding the peak that was reached during the boom prior to the Lehman Brothers collapse. Moreover, this yield has grown to three times the nominal return on government bonds. Holders of U.S. stocks receive a return of 6% based solely on the return of cash. In comparison, holders of U.S. Treasurys receive a real return that is negative. The yield gap has become extreme. No one should be surprised that savers refuse to stand by idly when the Fed takes actions aimed at narrowing this gap.

Distributions of corporate earnings through stock are giving households more spending power by increasing their assets, providing dividend income and in other ways. These funds are supporting a recovery in consumer spending. Interest, dividends, rent and other income from assets accounts for a very large share of U.S. household income. Household earned labor income (pure wages excluding fringe benefits) in the fourth quarter of 2011 totaled $6.7 trillion. Asset income (interest, dividends and rent) was $2.2 trillion of this amount. The high level of income from assets demonstrates the effectiveness of using rising stock prices and dividends to enable a recovery in corporate earnings to boost household income and thus consumer spending. In Japan, income from assets is an extremely small 4% of household income. Consequently, unlike in the United States, there is virtually no channel for translating a recovery in corporate earnings into higher consumer spending.

Critics of extreme monetary easing have no ground to stand on

Extreme monetary easing by central banks is obviously a powerful force behind the stock market rally. Balance sheets have grown at a breathtaking pace at the Fed after the Lehman Brothers collapse and at the ECB since the Greek debt crisis started about two years ago. Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, who has established targets for inflation and employment, is openly encouraging people to take on risk. The ECB as well has embarked on a massive quantitative easing program in response to the deepening debt crisis. Naturally, there is intense criticism of zero interest rates and extreme monetary easing. However, this criticism is losing its persuasiveness in the face of the current rebound in stock prices.

Bill Gross does not believe strong earnings are a reason to buy stocks

Curiously, U.S. and British newspapers both published articles yesterday that are critical of zero interest rates. Bill Gross, the founder of the PIMCO bond fund, had an op-ed piece in The Financial Times (February 7, 2012) in which he stated that “zero-based money risks trapping the recovery.” He explained that money lenders conduct financial activity when there is a normal gap between short and long-term interest rates. But even when this gap disappears (yield curve flattens) because of monetary tightening, investors expect that falling interest rates will produce capital gains. As a result, the credit markets function. However, when all interest rates fall to virtually nothing, as is the case in Japan, banks no longer have any incentive to make long-term loans because of the extremely small yield gap. Moreover, investors like banks and PIMCO have no reason to buy long-term government bonds because there is virtually no hope for capital gains. In a world like this, markets completely lose their dynamism as has happened during Japan’s lost 20 years. Certainly no one can deny that opportunities for arbitrage between long and short-term interest rates for same class bonds are lost in a world of “zero-based money.” On the other hand, when corporate earnings are strong, zero interest rates produce a big increase in the risk premium for stocks. The result is highly attractive investment opportunities in sectors other than government bonds. By extending his investment area to include stocks and credit assets with low ratings, Mr. Gross is most likely capitalizing fully on these opportunities. This represents absolutely no criticism at all of the Fed’s belief that boosting stock prices by lowering the risk premium is a key to achieving an economic recovery.

Charles Schwab’s optimistic view justifies the stock market rally

The Wall Street Journal carried an op-ed piece by Charles Schwab on the same day with the title “The Fed Votes No Confidence.” Of course, Mr. Schwab is critical of zero interest rates. He states that continuing the emergency measure of near-zero interest rates will increase instability in the future by sending a signal of crisis, not confidence . Although the Fed’s emergency measures are appropriate during a crisis, these measures are no longer needed because the economy is already recovering. Now is the time to trust the markets. Mr. Schwab’s criticism of zero interest rates is based on an optimistic outlook. While he may be correct, there is also a chance that he could be wrong. Due to this uncertainty, continuing supportive policies until the recovery gains more strength may be a safer course of action. Even if the Fed halts its emergency measures because employment recovers faster than expected, the resulting big boost in self-confidence at that time would give the recovery even more momentum. This explains why criticism of zero interest rates would no longer be persuasive.

Today is nothing at all like Japan’s lost 20 years

Bill Gross and other pessimists overemphasize similarities between the current situation and what happened in Japan. First, unprecedented earnings at U.S. companies represent a decisive difference between today and Japan immediately before deflation began. Earnings have grown because of a remarkable improvement in productivity backed by globalization and the Internet revolution. Second, the resolve of central banks is clearly different. The Bank of Japan decided to enact policies aimed at crushing the asset bubble. But monetary easing was implemented after deflation had started and then deflationary forces became firmly entrenched because of the resulting high real interest rates. In the United States, monetary easing came first and the result was consistently negative real interest rates. Furthermore, the U.S. enacted financial policies that pushed up asset prices by lowering the risk premium. Collectively, these actions sparked an upswing in the stock prices of companies that had already completed their restructuring programs.

The Japanese investment climate is rapidly moving away from pessimism

If the situation in Europe improves and the U.S. stock market upturn becomes a full-scale rally, we are very likely to see an end to the yen’s strength that was backed by investors’ aversion to risk. In fact, the conditions for selling the yen are becoming increasingly evident. Talk of a plunge in Japanese government bond prices is spreading because of the crisis in Greece and efforts by the Japanese Ministry of Finance to shape public opinion. Furthermore, Japan posted its first trade deficit in 31 years and the country’s working-age population is expected to fall rapidly. Supply-demand dynamics are shifting, too. Causes include the steep increase in Japan’s direct overseas investments and asset purchases by Japanese financial institutions associated with the debt crisis in Europe

There will be headwinds from policies that appear to have permitted a strong yen along with deflation. But global tailwinds may lead to an upward correction in prices of Japanese stocks that have long been the only losers in the world.

Figure 2 shows the cash return on U.S. stocks, which is the sum of dividends and buybacks divided by market capitalization. The dividend-buyback yield has climbed to an all-time high, excluding the peak that was reached during the boom prior to the Lehman Brothers collapse. Moreover, this yield has grown to three times the nominal return on government bonds. Holders of U.S. stocks receive a return of 6% based solely on the return of cash. In comparison, holders of U.S. Treasurys receive a real return that is negative. The yield gap has become extreme. No one should be surprised that savers refuse to stand by idly when the Fed takes actions aimed at narrowing this gap.

Figure 2 shows the cash return on U.S. stocks, which is the sum of dividends and buybacks divided by market capitalization. The dividend-buyback yield has climbed to an all-time high, excluding the peak that was reached during the boom prior to the Lehman Brothers collapse. Moreover, this yield has grown to three times the nominal return on government bonds. Holders of U.S. stocks receive a return of 6% based solely on the return of cash. In comparison, holders of U.S. Treasurys receive a real return that is negative. The yield gap has become extreme. No one should be surprised that savers refuse to stand by idly when the Fed takes actions aimed at narrowing this gap.

Distributions of corporate earnings through stock are giving households more spending power by increasing their assets, providing dividend income and in other ways. These funds are supporting a recovery in consumer spending. Interest, dividends, rent and other income from assets accounts for a very large share of U.S. household income. Household earned labor income (pure wages excluding fringe benefits) in the fourth quarter of 2011 totaled $6.7 trillion. Asset income (interest, dividends and rent) was $2.2 trillion of this amount. The high level of income from assets demonstrates the effectiveness of using rising stock prices and dividends to enable a recovery in corporate earnings to boost household income and thus consumer spending. In Japan, income from assets is an extremely small 4% of household income. Consequently, unlike in the United States, there is virtually no channel for translating a recovery in corporate earnings into higher consumer spending.

Distributions of corporate earnings through stock are giving households more spending power by increasing their assets, providing dividend income and in other ways. These funds are supporting a recovery in consumer spending. Interest, dividends, rent and other income from assets accounts for a very large share of U.S. household income. Household earned labor income (pure wages excluding fringe benefits) in the fourth quarter of 2011 totaled $6.7 trillion. Asset income (interest, dividends and rent) was $2.2 trillion of this amount. The high level of income from assets demonstrates the effectiveness of using rising stock prices and dividends to enable a recovery in corporate earnings to boost household income and thus consumer spending. In Japan, income from assets is an extremely small 4% of household income. Consequently, unlike in the United States, there is virtually no channel for translating a recovery in corporate earnings into higher consumer spending.