Jan 26, 2012

Strategy Bulletin Vol.62

Why is Japan performing so poorly?

~ The policy differences behind the gaps in stock prices ~

Yoshikawa’s views vs. Summers’s views

The article titling “the income distribution and the direction of the world economy” by Hiroshi Yoshikawa, professor at Tokyo University, the most trusted economist making great influence over politics, was placed in weekly Tokyokeizai magazine on Jan. 28. In the meanwhile, the comment “Economic uncertainty is no excuse for inaction” made by Lawrence Summers, Charles W. Eliot university professor at Harvard, and economist, who has the most considerable effect to deals in US, was put in Financial Times on Jan. 24. Both of them are indeed representative economic intellectuals based on Keynesian economics , however, their discussions are conflicting.

The resigned and passive stance of Professor Yoshikawa

Professor Yoshikawa believes that developed countries already have a weak structure in which the increasing use of products and services quickly leads to demand saturation. Keynes, who recognized this problem, believed that the solution for ending chronic inadequate demand is to shift income to low-income individuals because they have a higher propensity to consume. However, in the United States and Britain, there is now an extreme concentration of income among very wealthy individuals. As a result, it is impossible to reach a consensus in these countries to use fiscal measures for the redistribution of income. This situation was behind the idea of extending sub-prime loans to low-income individuals, which then led to the financial crisis. Furthermore, the crisis in Europe as well was caused by the lack of an economic mechanism (fiscal integration) for narrowing the income gap in EU member countries. He concludes that the income gap and difficulty of redistributing income by using fiscal measures are at the bottom of the financial crisis. The result is the emergence of a problem that cannot be resolved in a short time.

The optimistic and activistic stance of Professor Summers

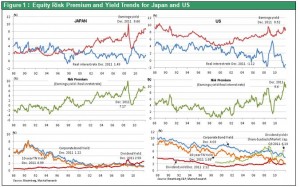

Professor Summers believes that anxiety about the future is a major driver of economic performance. In the U. S., the yield on 10-year U.S. indexed bonds is currently negative. That means investors are paying the U.S. government to store their money for 10 years. At the same time, the S&P 500 is expected to be selling at only 13 times earnings. This demonstrates the magnitude of fear about the future. Uncertainty about future growth prospects also correlates with other observations, such as the abnormally large amount of cash sitting on corporate balance sheets, the reluctance of companies to hire, and consumers’ hesitancy about big discretionary purchases of durable goods. All of this suggests that for the industrial world as a whole, the priority for governments must be to engender confidence. The result is a debate regarding how to achieve this goal and whether or not to increase government spending. Seventy-five years ago, John Maynard Keynes saw through this sterile debate, writing to President Franklin Roosevelt that either “the business world must be induced, either by increased confidence in the prospects through a lower rate of interest”, or “public authority must be called in aid to create additional demand through the expenditure of borrowed or printed money”. Government has no higher responsibility than insuring economies have an adequate level of demand. Without growing demand, there is no prospect of sustained growth, let alone a significant fall in joblessness. And without either of these there is no chance of reducing debt-to-income ratios. To boost demand when businesses are understandably uncertain about their prospects new regulations that burden investment and policies for correcting inequality should be postponed.

The remarkable gap between policy positions

The positions of these economists differ greatly even though both views originate from the same framework of economics. Professor Yoshikawa believes that there can be no true economic recovery in developed countries without a change in the framework of policies involving income redistribution. There is a limit to what governments can do. Professor Summers, on the other hand, believes that abnormally high fear is the cause of economic problems. He thinks that governments can assume the responsibility to make the improvements needed to achieve a sustained economic recovery. Authorities in Japan have adopted the Yoshikawa position. This is why the Japanese government is currently focusing on altering its fiscal framework while putting an economic recovery and anti-deflation initiatives on the back burner for the time being. The United States has embraced the Summers position by starting to do everything possible to trigger an immediate rebound in demand. The unprecedented monetary easing by the Fed is at the core of these activities. The difference between these two positions is clearly evident in the performance of Japanese and U.S. stocks.

The extreme difference between the performance of Japanese and U.S. stock

Japanese stocks have posted the worst returns in the world for the past several years. Stock prices worldwide plummeted 60% after the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers. But stock markets then staged a powerful rally. At the 2011 peak, stock prices were twice as high as at the 2008 low. Stocks in Japan fell too in 2008 but subsequently rebounded only 40%. Furthermore, stock markets of the world fell more than 20% in 2011 when the European financial crisis started but then rose more than 10%. In Japan, though, stock prices are still at the same depressed level as in 2011. Compared with their highs prior to the Lehman Brothers collapse, U.S. stock prices are down by 10% and German stock prices are down by 20%. But stock prices in Japan are still down by a dismal 50%. Stock prices are not the only problem. Japan has also fallen behind based on manufacturing, exports and other indicators of the strength of its recovery after the economy hit bottom following the Lehman shock. Natural disasters like the Great East Japan Earthquake and flooding in Thailand are one cause of Japan’s economic weakness. But the yen’s strength and the reemergence of deflation are probably even more significant factors. We are witnessing a conditioned reflex in which global economic problems prompt investors to turn to the yen. The yen is not strong because investors have a favorable view of Japan’s economy. Instead, a peculiar habit has taken hold among international investors that causes their preference for the yen to strengthen in proportion to the increase in global economic problems.

The yen’s strength in the absence of policy initiatives puts Japan at a disadvantage

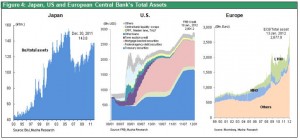

As the yen appreciates, wages of Japanese workers rise in relation to wages in other countries. The result is growth in downward pressure on wages in Japan. Furthermore, a strong yen brings down prices of imported goods, creating another source of deflation. Therefore, deflation is a condition for the yen to become even stronger because lower prices boost purchasing power. This explains why Japan has become entrapped in a inescapable plight consisting of a strong yen and deflation. These forces are having a severe impact on the ability of companies to compete and earn profits. China, which has the world’s largest trade surplus, has been practically linking its currency to the U.S. dollar. Germany, which has the second-largest trade surplus, uses the euro and is thus benefiting from a weakening currency. Only Japan, which has a smaller trade surplus, had the misfortune to draw the lottery ticket of strong-currency poverty. Germany, which is involved in the euro crisis, is beginning to benefit from a sharp drop in interest rates and the weakening euro. Interest rates in southern European countries have surged since the crisis in Europe started. At the same time, though, Germany has seen a rapid downturn in the interest rates it pays. Germany, even with its negative real interest rates, has become a safe haven for investments in Europe. The resulting inflow of funds will probably fuel domestic demand in Germany as well as inflation. The United States too has significantly negative real interest rates due to the benefits of vigorous monetary easing initiatives by the Fed. In contrast, real interest rates in Japan are very high because of deflation. This is a significant contributor to higher expenses at Japanese companies. After taking these factors into consideration, we can conclude that the conspicuous weakness of Japanese stocks should come as a surprise to no one. Differing stances of central banks, as can be seen in the differences in monetary bases and other parameters, are what set the United States, Germany and Japan apart. The fed are responsible for achiving dual mandate maximum employment and price stability, which are blatantly encouraging people to take on risk. In response to the deepening financial crisis in Europe, the ECB as well has embarked on a massive monetary easing program. Just like at the Fed, it is time for the Bank of Japan too to provide a large volume of base money and to do everything possible to end deflation and spur economic growth.