Dec 06, 2011

Strategy Bulletin Vol.60

Debt-based Historical View vs. Productivity-based Historical View (Part 5)

Resolving the euro trilemma and saving Europe from the debt crisis

People who are viewing the current situation in Europe from a debt-based perspective are becoming increasingly pessimistic (Kenneth Rogoff, for example). These individuals believe that Europe is about to enter a dark age in which excessive debt will have to be dealt with. But people who embrace the productivity perspective believe that the debt crisis happened because an improper situation is blocking economic growth. This stance provides a reason to believe that growth is possible in the future. My position is that the crisis itself is an opportunity to build a foundation for future economic growth (a crisis is equivalent to an opportunity).

The financial market rather than government finances is the fundamental cause of this crisis

“A paralysis of financial markets caused by unified interest rates throughout the euro zone” is the biggest barrier to growth of the euro. Most people believe that government deficits are the cause of the euro crisis. However, the inability of financial markets to properly allocate resources is the actual cause of the irresponsible budget management of European countries. Since the euro was launched 12 years ago, there has been a widening imbalance within Europe in terms of inflation (wage inflation), productivity, fiscal moderation and economic growth. If nothing is done, this imbalance may result in the euro’s collapse. The decade was a period when capital flowed in a single direction: to southern European countries with high inflation, strong economic growth, low productivity and a lack of fiscal discipline. This created bubbles that wasted this capital and made the imbalance among the regions of Europe even greater.The euro is caught in the trilemma trap

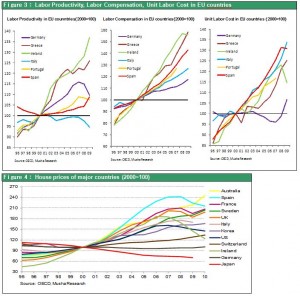

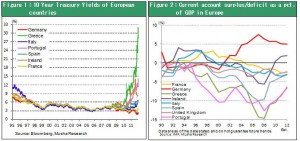

The euro zone has been entrapped in a so-called “international finance trilemma” for the past decade. As Figure 1 shows, there were considerable differences in long-term interest rates among euro zone countries until the euro’s 1999 launch. These differences completely disappeared between 2000 and 2008, resulting in the same interest rates (both long and short) throughout the euro zone. But examining this matter more closely reveals that unified interest rates were not consistent with economic rationalism, or in other words the proposition of the “international financial trilemma,” The “international financial trilemma” refers to the inability to simultaneously achieve unrestricted movements in (1) foreign exchange rates, (2) interest rates and (3) transfers of capital. China is artificially controlling its (1) exchange rate. A country that does this has no option other than to (3) restrict transfers of capital because (2) the freedom of domestic interest rate movements cannot be abandoned. When the “pound shock” occurred in 1992, the United Kingdom attempted to (1) maintain unrestricted foreign exchange rate movements (hold foreign exchange rate volatility within the EMS to within 2.25%) while (2) preserving the freedom of movements of capital. However, the freedom of domestic interest rate movements was lost, which resulted in the trap of a sharp upturn in interest rates that led to a recession. In the end, the United Kingdom had to select (2) freedom of interest rate movements in order to prop up its economy and, as a result, was forced to abandon the freedom of foreign exchange rates. Since then, the United Kingdom has placed priority on the freedom of domestic interest rates and entrusted markets with the responsibility to determine the exchange rate for the pound sterling.

A return to euro zone interest rate differentials is both a natural and desirable trend

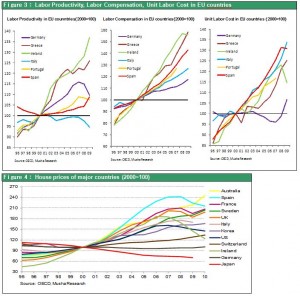

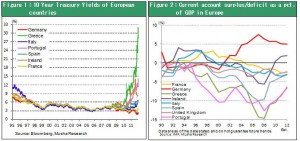

As you can see, China and the United Kingdom each has a clearly defined set of priorities in order to maintain economic and financial stability. However, until 2008, euro zone countries were attempting to achieve all three freedoms at once: (1) a fixed exchange rate within the zone, (2) unrestricted interest rate movements (same interest rate throughout the zone), and (3) the free movement of capital. This was clearly contradictory to the proposition of the “international financial trilemma.” Simultaneously achieving (1), (2) and (3) causes a steadily growing disparity in the competitive position of each region and in other imbalances. Therefore, until 2008, the euro’s unified interest rates created a systematic defect that would lead to the euro’s collapse because of widening imbalances. Figure 2 shows the current account balance in relation to GDP, a figure that reflects the ability of each European country to compete. This figure shows that Germany’s position as the sole winner has become increasingly pronounced. Germany was winning because of the significant gap between the country’s wage and unit labor cost increases. Financial markets made this difference even larger. As you can see in Figure 3, wages in Germany increased by less than 20% over the past decade, far below the increases of 40% to 60% in southern European countries. A comparison of housing prices in major countries is also instructive. During the past decade, as the world was caught up in the frenzy of a bubble economy, housing prices declined only in Germany and Japan (Figure 4). Unified euro zone interest rates produced low real interest rates in southern Europe where inflation was high. The result was accelerating inflation in southern Europe and high real interest rates in Germany, where inflation was low. These high real interest rates brought down Germany’s inflation even more, making the country much more competitive. Viewed from this perspective, we can see that the reemergence of significant long-term interest rate differentials among euro zone countries since 2009 is consistent with economic rationality and signifies the end of the “international financial trilemma” In Germany, falling interest rates and capital inflows stimulated the country’s economy and inflation. In southern Europe, the situation was exactly the opposite as interest rates climbed and capital was shifted to other regions. The result was a natural correction in gaps in competitiveness and in imbalances. Interest rate differentials probably make it even easier to maintain euro zone unity, but only if interest rates in southern Europe do not climb to a destructive level. These interest rate differentials will reduce the public sector’s fiscal burden smaller adjustments are made for imbalances. Consequently, fiscal unification will be even easier to accomplish.