The possibility of “sudden death” of banks is the real cause of this crisis

A liquidity crisis sparked by the Greek debt problem is the real cause of the global plunge in stock prices that began in August. Short-term interest rates for interbank loans in Europe, including indicators like the OIS spread and TED spread, have surged. Banks in Europe are having difficulty procuring dollars. Siemens transferred deposits from a French bank to the ECB (The Financial Times, September 20). The average correlation of stocks in the Russell 1000 Index has topped 80%, which is higher than at any peaks of past crise like Black Monday, the bursting of the IT bubble and the Lehman shock (The Financial Times, September 23). All these events demonstrate that the world’s financial markets are bracing themselves for the “sudden death” of financial institutions in Europe. Once again, we are seeing stock prices plummet around the world just as they did after the Lehman shock.

Markets are enveloped with fear about the possibility of a financial panic resulting from a Greek default that causes the collapse of European financial institutions that have loaned funds to Greece. In the worst case scenario, a Greek default could lead to similar problems in Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy. Ultimately, this would destroy the euro. Under these emvoronment occupied by fear , analysis and other data concerning the economies and solvency of various countries would become largely meaningless. The difference between the solvency of Italy and Greece would be pointless. As a result, financial markets are focusing their attention on one question: whether or not the possibility of “sudden death” at one or more banks can be eliminated.

The cause of the Greek debt crisis is “governments without a wallet”

The euro zone contradiction of “government spending without a wallet” is behind the spread of the Greek debt crisis. Serving as a “government’s wallet” is the most important role of any central bank. Most governments have a “wallet” known as a central bank that makes it possible to enact self-reliant fiscal policies. In the euro zone, though, countries control their own fiscal policies but do not have their own wallets. This forces governments to use financial markets to procure funds. That means governments are at the mercy of the perceptions of market participants just as companies are. European banks holding massive volumes of government debt, which should be absolutely safe, are now facing the possibility of insolvency. If quick fiscal unification is not possible, the next-best step is to create a public finance “wallet” for all euro zone countries. Ongoing measures to enlarge the size and functions of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) are precisely an attempt to accomplish this. The EFSF is a scheme for having the public sector cover losses that should be the responsibility of banks. If this facility functions as planned, the resulting guarantees of government debt will make worries about the stability of banks disappear.

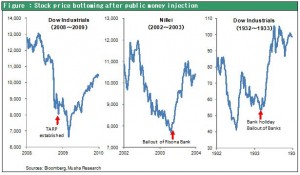

Infusions of public funds have triggered a strong stock market rally in the past

Stock prices have always stopped falling in the past under similar circumstances.

(1) After the Lehman shock, there was a reversal in interest rates and stock prices due to enactment by the United States of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) amid intense criticism of banks. TARP was approved by Congress in October 2008. One month later, the downturn in long-term interest rates ended. Once investors confirmed progress made with implementing TARP, stock prices bottomed out four months later, although extra time was needed to deal with supply-demand imbalances caused by the withdrawal of cash from hedge funds.

(2) In May 2003, the Japanese government decided to rescue Resona Bank, which was the target of criticism by the media and others, with an infusion of public funds (but did not completely nationalize the bank). Following this action, a long-term decline in stock prices in Japan ended and stock markets staged a powerful rally (stock prices reached a major bottom in April 2003).

(3) Even during the Great Depression, stock prices started a rapid recovery after the administration of newly elected President Roosevelt in February 1933 provided public funds to banks (in association with bank closings and integrations). This followed the end of the administration of President Hoover, who had placed priority on eliminating problems that occurred in the past. Stock prices doubled over the next year (stock prices reached a major bottom in June 1932).

Consequently, there are excellent prospects for a V-shaped recovery in stock prices after banks receive an infusion of public funds. If expansion of the size and functions of EFSF can be accomplished successfully, we will probably see a dramatic change in the environment for financial markets.