A condemnation of overly hasty exit measures

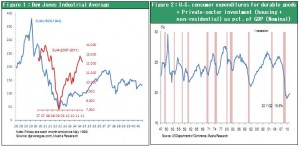

Once again we are seeing a worldwide plunge in stock prices. A significant barrier to the upward trend in stock prices that started after Lehman shock is emerging. Market sentiment has rapidly cooled due to the ineffectiveness of governments. This sentiment is inflicting severe damage to the long-awaited animal spirit that was finally reappearing as investors took on risk to earn profits in the future. Current events bring back memories of the nightmare of 1937 when another economic recession started. Between the start of the Great Depression in 1929 and 1932, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted 89% from $380 to $42. By March 1937, the average had rebounded more than fourfold from the bottom to $186. However, the excessively hasty adoption of restrictive fiscal policies and monetary tightening caused the average to drop sharply to $99 by March 1938. Stocks lost half their value in only 12 months as another economic recession started in the United States. Today’s events are strikingly similar to 1937: exit measures enacted too quickly as the problem of insufficient demand remained unsolved caused investor sentiment to become negative.

A switch from restrictive policies is needed

We have reached the point to expect a further drop in stock prices to force governments to alter their policies. However, the failure of government policies is still minimal compared with the situation in 1937 and can be corrected. Fortunately, the control tower for global finances is in the hands of U.S. Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, who has extensive knowledge about the events of 1937. Falling stock prices may end the global move toward cutting government spending and prompt countries to embark on a joint monetary easing program. If this happens, we may see the steep drop in stock prices and the economy become a powerful rebound. Even in 1937, when governments were unable to correct their severely mistaken policies, stock prices staged a 60% rally over the 9-month period after the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit bottom at $90.

The restrictive fiscal policies that dealt a fatal blow to the economy in 1937 were extreme. U.S. government expenditures fell 20% from 1936 to 1938 (from $8.4 billion in 1936 to $7.7 billion in 1937 and $6.8 billion in 1938). At that time, financial policy was controlled by conservative libertarians who stubbornly demanded a smaller government. This stance is quite similar to today’s Tea Party. The recent agreement to cut expenditures calls for a reduction of $2.4 trillion over 10 years. That translates into an annual cut of $240 billion, which is about 10% of total annual budget. A number of this size cannot be ignored. But only $90 billion of the $240 billion in reductions has been decided. Revisions are possible because the remaining cuts will be determined by negotiations by members of Congress. Moreover, the United States is retaining its positive stance with regard to liquidity measures. As a result, consistent growth can be sustained if there is international cooperation to resolve the European debt crisis and other problems and if governments take actions like QE3 that reflect lessons learned from past mistakes.

The sources of U.S. difficulties: Unprecedented earnings and the worst unemployment in the post-war era

A stark contrast between good and bad in the economy is the source of the current economic problems in the United States. Companies are reporting record earnings. At the same time, though, unemployment is at an all-time post-war high. Earnings do not generate demand or jobs. The productivity revolution is the cause of this disparity. A global productivity revolution of unprecedented scale is taking place that is fueled by globalization and the Internet revolution. Companies face constant competition to build the best business models. Rising productivity allows companies to cut labor costs. Although this boosts earnings, the number of jobs declines. This is the cause of stagnant household incomes and inadequate demand. But we must remember that higher productivity should mean that companies can supply more goods by using the same amount of labor. If demand fails to grow, the only option companies have is to reduce their workforces to prevent an oversupply of goods. This is why a productivity revolution by its very nature tends to be a cause of insufficient demand.

Can the U.S. simultaneously resolve the problems of too little spending and too much saving?

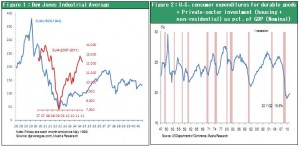

One more cause of insufficient demand is the after-effects of the housing market bubble. U.S. discretionary spending (expenditures that are not necessary or urgent: durable goods, housing and capital expenditures) in relation to GDP has fallen to the lowest level in the post-war era, as you can see in Figure 2. That means demand in the United States has been compressed to an unprecedented point. In other words, demand is being shifted to the future. Furthermore, there is excessive savings in the U.S. private-sector economy. Falling home prices and worries about jobs are making households cut spending while raising the savings rate too much (to more than 5%). With earnings rebounding and investments remaining flat, companies have a large volume of excess cash. This explains why too little demand and too much savings can exist side by side.

Animal spirits are what link demand and savings. This is the willingness to make a greater commitment to long-term purchases. People buy only what they absolutely need when they become extremely worried. Once their confidence returns, though, people start purchasing goods with an increasingly longer life. Purchases shift from food to clothing, home appliances, automobiles and finally furniture and houses. In addition, people shift from renting houses to buying houses. Companies as well shift to longer-term commitments. Instead of making only the minimum expenditures needed for maintenance, companies start making investments to increase output capacity, enter new business fields and purchase assets that will be used for many years. As people and companies increase purchases and investments with a longer-term perspective, the depth of demand increases. Right now, demand in the United States is extremely shallow because of the unprecedented degree of emphasis on short-term purchases. This situation clearly shows the enormous decline in animal spirits that has taken place.

Responding to turmoil in financial markets will require rebuilding global initiatives to achieve reflation. The need for reflationary policies is particularly urgent in Japan, which is dealing with an abnormal upturn in the yen’s value. This is why Japan must become the driving force behind the enactment of reflationary policies on a global scale.