The positive signs in the weekly chart

A major positive indicator has emerged in the weekly candlestick chart for the Nikkei Average: the short black candlestick of two weeks ago (second week of July) has been surrounded by the long white candlesticks of last week (third week of July) and three weeks ago (first week of July). Furthermore, we will almost certainly see a golden cross appear within a few weeks. This will happen when the 13-week moving average breaks through the 26-week moving average from below.

However, the current stock market rally in Japan has two unexpected characteristics. First is the simultaneous upturn in the yen and stock prices. Many people with a positive outlook, including me, based this outlook on the expectation for an end to the yen’s strength, which would boost corporate earnings and end deflation. Shouldn’t we be surprised to see Japanese stocks climb even as the yen becomes stronger? The second characteristic involves the proposal at last week’s emergency summit in Europe for a stopgap measure to resolve the Greek debt crisis. As this happened, the yen continued to strengthen despite the global trend toward the resumption of risk-taking. Until now, the yen’s strength was a symbol of global risk aversion. But the suspicious nature of these two unexpected characteristics is also giving investors doubts about the positive signs for the stock market.

Why is a strong yen good for Japanese stocks?

How do we explain the dual upturns in the yen and Japanese stocks? We should probably recognize the undercurrent of easing deflationary pressure even as the yen climbs.

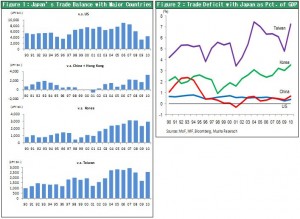

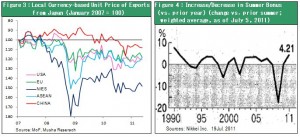

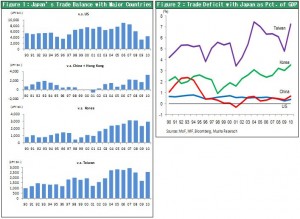

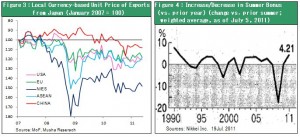

The first reason for the dual upturns is that Japan’s export unit price (in yen) has stopped falling despite the yen’s strength. As you can see in Figure 1, the yen alone among major global currencies has been appreciating since 2007. But Figures 2 and 3 show that Japan’s export unit price in terms of destination country currencies has increased significantly starting in 2009.

There is a small upturn even for yen-based prices. Since 2000, Japanese exporters have been consistent losers regarding price competition with companies in Korea, China and Taiwan. Most of the remaining products that Japan can export are goods that do not use prices to compete (products with exclusive technologies). Japan can still export products such as high-tech materials, parts, devices and other components that cannot be made in Korea, China and Taiwan. This explains why a stronger yen does not cause export volumes to fall. In fact, a strong yen contributes to growth in Japan’s trade surplus by boosting US dollar-denominated export prices. Naturally, a strong yen is bad news for Japanese companies in industries like automobiles, shipbuilding and consumer electronics that compete with Korean companies. But these sectors now account for far less than half of Japanese export value.

The second reason is the increasing resilience of Japan’s exporters to a strong yen. An upturn in the yen no longer produces downward pressure on wages in Japan. Workers that exporters hire in Japan are not the inexperienced, low-paid laborers in countries with which Japan competes. All are technocrats with expertise in engineering, marketing or management. This is why summer bonuses in Japan are up 4.2% from last year despite the strong yen and the recent earthquake and tsunami (Nikkei Shimbun, July 19). (Figure 4)

The third reason is the big drop in the cost of imports that results from a strong yen. The rising yen largely offset the increase in the cost of crude oil and cut costs for companies that sell imported goods. Benefits have been great for companies like apparel retailers, convenience stores, miscellaneous goods stores, 100-yen shops, and other stores that are behind Japan’s distribution revolution. These sectors have further lowered their costs significantly by benefiting from the Internet revolution and other advances in technology. Falling prices at these stores have in turn raised the real purchasing power of Japanese households. Shouldn’t we conclude that deflationary pressure in Japan is easing even as the yen appreciates?

A reversal of the yen will add momentum to the stock market rally

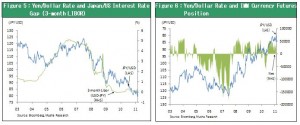

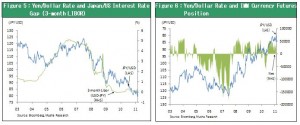

Obviously the current upturn in the yen does not seem to have any economic rationale and is probably not sustainable. As Figure 5 shows, the interest rate gap does not justify the current strength of the yen. However, in terms of supply and demand, the correction following the long dollar positions that were established up to 2007 may still not be finished (Figure 6). The popularity of foreign exchange margin trading in Japan resulted in remarkable growth in short yen positions by individuals and small and midsize companies between 2005 and 2007. The recent upturn of the yen along with a reduction in the limit on margin trading leverage (from 50 to 25 times in August 2011) may be increasing pressure on investors to cut their losses by purchasing the yen.

According to the OECD, the yen/dollar exchange rate should be \111 (2010) based on purchasing power parity. Moreover, if U.S. short-term interest rates start climbing due to clear signs of U.S. economic growth, the widening interest rate gap will push the dollar higher and the yen lower. I believe this will happen in the second half of 2011 and 2012. Once the yen reverses direction, relative wage level of Japan will drop sharply in comparison with other countries. This will probably increase pressure for wage hikes in Japan, bringing a conclusive end to deflation and raising the country’s economic growth rate.

As I have noted, the current stock market rally in Japan began as the yen continued to climb. But a reversal to a weaker yen would most likely increase prospects for this rally to gain momentum. When the yen is strong, investors naturally turn their attention to stocks associated with domestic demand. If the yen starts to weaken, though, investors will most likely shift their focus to Japanese companies that are global players.

<Reference>

Strategy Bulletin 38 (07Jan.2011)

Why does Japan’s trade surplus with China, Korea and Taiwan continue to grow?

Asia’s flying-geese growth pattern with Japan leading the way

News headlines are overwhelmingly pessimistic

Most people are convinced that economic power in Asia is shifting as China and Korea become stronger and Japan declines. There are many reasons for this widespread belief. For example, (1) stores in Japan are filled with merchandise from China; (2) premier Japanese companies like Sony, Panasonic, Toyota and Honda are weakening as companies like Samsung (the world’s largest manufacturer of semiconductors and electronic products) and Hyundai grow rapidly; (3) Japan’s industrial sector is hollowing out as companies move factories to other countries; and (4) Japanese companies are suffering steep declines in their market shares for most advanced electronic products, such as semiconductors, cell phones and LCD TVs. This explains why almost all news stories about Japan are reports about the country’s decline.

Japan is the only winner in trade balances within East Asia

However, there is one enormous fact that is in direct opposition to the belief that Japan is weakening. Trade balances of East Asian countries reveal that Japan alone is the winner. Japan’s trade surplus with China, Taiwan and Korea is currently posting strong growth. Most significantly, Japan’s trade surplus with China (including Hong Kong) surged to an estimated \4 trillion in 2010. Furthermore, the trade deficits in Korea and Taiwan are rising rapidly as a percentage of these two countries’ GDPs. Based on 2010 estimates using data for the year’s first 10 months, Taiwan’s trade deficit with Japan was 7.2% of its nominal GDP and this percentage increased to 3.6% in Korea. Both percentages are now at very high levels. In China as well, the trade deficit with Japan has increased significantly in relation to GDP. The percentage was an estimated 0.7% in 2010. In comparison, Japan’s trade surplus with the United States fell sharply in 2009 and then recovered somewhat in 2010. As a result, this surplus is now much lower than before as a percentage of Japan’s GDP.

Japan’s superiority is becoming increasingly apparent

How should we interpret the conflicting trends of a rising Asian trade surplus and falling U.S. trade surplus? We can begin with the following three points.

(1) Japan’s presence is declining in the United States, which is an enormous market for home electronic products, machinery, automobiles and other finished products. Manufacturers in Japan specialize in high-end products and high-tech capital goods. Companies in Korea, China and Taiwan have competitive edge in the volume zones of finished products. This explains the big downturn in Japan’s trade surplus with the United States.

(2) There is a clear division of roles within Asia. Japan is specializing in high-tech materials (chemicals, metals, ceramics, etc.), high-tech components and high-tech machinery. For finished products, Japanese companies are focusing increasingly on high-end products and state-of-the-art technologies. These companies have shifted the production of volume-zone finished products to Asia.

(3) There is a technological “black hole” in all of the product sectors that Japan is targeting: high-tech materials (chemicals, metals, ceramics, etc.), high-tech components and machinery, and high-end finished products incorporating advanced technologies. These products have a decisive competitive edge that is not linked to their prices. Manufacturers located in other Asian countries cannot easily keep up with Japanese products. In addition, since Japan controls the prices of its high-end products, dollar-denominated export prices can be raised when the yen strengthens (Customs statistics show that export prices of goods shipped from Japan to Asia have not declined at all despite the yen’s strength.). This explains the increase in Japan’s trade surplus with other Asian countries.

The flying-geese division of roles in Asia

The following division of roles in the Asian economy is now emerging.

(1) Concentration in Japan of highly technology-intensive “black box” products (materials, components, equipment)

(2) Concentration in Korea and Taiwan of the final assembly of products that are somewhat technology-intensive

(3) Concentration in China and Southeast Asian countries of labor-intensive assembly processes

Multinational companies (including Japanese manufacturers) are establishing supply chains that cover all of Asia: Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China and Southeast Asia. As companies establish these supply chains, the division of companies’ production processes becoming even easier to see.

In Korea, the growth of companies like Samsung and Hyundai generates increasing demand for black-box products made in Japan. As a result, Korea is forced to import more high-priced goods from Japan. This is the reason for growth in Korea’s trade deficit with Japan. Consequently, we are seeing the emergence in Asia’s manufacturing sector of a flying-geese division of roles with Japan at the forefront. This situation indicates that the Japanese economy will be able to preserve its competitive edge. Clearly, the widespread pessimism about Japan in financial markets is far off target.

Examining Japan’s superiority as a new year begins

(1) Pessimism about Japan is deeply rooted. The primary reason that pessimists use for their beliefs is the absence of prospects for economic growth in Japan. They point to a declining number of workers and shrinking markets as the population falls. But we can refute this stance by extending Japan’s economic zone to encompass all of Asia. Adopting this view eliminates the limitations on economic growth imposed by a declining labor force and shrinking markets.

Japan is the only highly developed global economy in the high growth potential Asia region. Creating industrial and market zones centered on Japan should yield substantial benefits involving synergies and networks. For instance, using Asian countries as production bases for Japanese companies gives these companies the supply-side benefit of access to inexpensive labor. An international comparison of wages in major countries reveals that Japan has the most expensive workers in the world because of the extreme appreciation of the yen. Manufacturing goods in other Asian countries can slash the cost of production by as much as 80% to 90%. This cost difference gives Japanese companies the opportunity to earn enormous extra profits. I call this the “cheap labor gift.”

Furthermore, as Japanese companies build factories in other countries, the degree of industrial concentration is increasing in China and other Asian countries. The result is an expanding industrial infrastructure, as can be seen in the rising volume of China’s processing trade (the so-called added-profit trade). Rising industrial density is spreading from China to low-cost countries like Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar. This has become a massive wave that is enveloping all of Asia.

If these changes cause incomes in China and other Asian countries to rise, Japanese companies would benefit from the resulting strong growth of markets in these countries. Internal demand in China has become an extremely large market for Japanese companies. Next, growth in internal demand will take place throughout Asia. Two years ago, the combined GDP of major Asian countries ($10 trillion) was already twice as large Japan’s GDP. In addition, Asia has a population of about 1 billion with incomes in the $3,000-$5,000 range or higher. This range is generally regarded as the starting point for a mass consumption society. If these countries become new markets for Japanese products, companies in Japan will have an excellent opportunity to offset the negative effect of Japan’s shrinking population.

(2) The next question is if Japan can become the location for the head offices of companies that operate in Asia. And can Japan retain this position? We may see the establishment of a business model in which goods, technologies and business plans are created in Japan. Manufacturing takes place in other Asian countries and products are then sold worldwide. If this happens, Japan’s scope of influence would grow from Asia to cover the entire world. Asia is now the world’s largest market. Asia’s prominence is producing renewed interest in the high cultural sophistication and standards, powerful brands and other strengths of Japanese companies, which are unparalleled even within Asia. The outstanding quality and powerful brands of Japanese companies are very appealing to consumers in Asia. The more affluent people in Asia become, the more they will want to buy Japanese products that excel in terms of added value and quality. Japan is attracting a growing number of tourists from China and other Asian countries. Tokyo shopping districts like Ginza and Akihabara are filled with Asian tourists. Obviously, these tourists want products and services that they believe are available only in Japan. Rising incomes in Asia will probably result in further growth in the number of these tourists. In this respect, growth of Asian markets will support the growth of Japan’s economy.

(3) Japan can probably retain a sufficient competitive edge as globalization progresses. Best illustrating Japan’s superiority is the country’s leadership in high-tech and other “black box” fields. These are business sectors where Japanese companies encounter no competition by supplying products with added value and know-how that competitors cannot match. Today, Korea’s Samsung is the world’s largest company in the high-tech sector. In fact, this company’s leadership is so great that Japan’s Panasonic and Sony can no longer see Samsung moving away in the distance. Furthermore, Chinese companies are highly competitive in terms of prices. This explains why there are so many products from China (including products made in China by Japanese companies) in Japanese stores.

Despite the success of Samsung and the popularity of Chinese goods, Japan has large trade surpluses with Korea, Taiwan and China. This is because Japan is far ahead of other countries in the production of materials and devices that are needed to fabricate high-tech products. Today, finished products are not the primary factor that determines technological superiority in the high-tech field. Instead, leadership depends on components and materials as well as the equipment used to assemble finished products from these components and materials. As long as Japanese companies retain their superiority in this field, China and Korea will find it very difficult to catch up. Japanese companies have a competitive edge in many fields outside the high-tech sector, too. One example is environmental products. Manufacturers in Japan are leaders in pure water equipment, reverse osmosis membranes for desalination, nuclear power and numerous other categories. Japanese companies have considerable expertise in many categories of the service sector, too.

(4) Japan’s service sector has a reputation for having low productivity. But this is nothing more than a statistical phenomenon caused by low selling prices and low value added for services in Japan. Based on a comparison of quality, Japanese companies provide the world’s highest level of services at hotels, restaurants, stores, taxis, parcel delivery services and many other service categories. If Japanese companies can raise prices to reflect the quality of their services more accurately, the service sector in Japan could quickly become an industry capable of generating substantial added value.

Japan also has the advantage of many highly attractive resources for tourism. Forests cover about 70% of Japan’s land area. This gives the country a natural environment on a scale that people would not expect to see in such a developed country. Okinawa has tropical islands similar to those in the Caribbean. Hokkaido has ski areas and central Honshu has mountains that rival those of Switzerland. No country has more hot spring spas. Kyoto and Nara have historical sites on a par with Rome. Tokyo is known as the world’s cleanest metropolis. Tourists can easily visit these places by using an extensive network of expressways and railroads. Japan also offers visitors four seasons to choose from. Overall, Japan has more than enough appeal to make the country highly competitive as a destination for tourism. There is no reason that Japan cannot become a prime tourism and sightseeing destination as the residents of Asia become increasingly affluent.

As I have explained, Japan has the resources to maintain a position of superiority in numerous respects as globalization continues to progress. Devising the best ways to leverage these strengths as much as possible will hold the key to ensuring that the Japanese economy can continue to grow.

The second reason is the increasing resilience of Japan’s exporters to a strong yen. An upturn in the yen no longer produces downward pressure on wages in Japan. Workers that exporters hire in Japan are not the inexperienced, low-paid laborers in countries with which Japan competes. All are technocrats with expertise in engineering, marketing or management. This is why summer bonuses in Japan are up 4.2% from last year despite the strong yen and the recent earthquake and tsunami (Nikkei Shimbun, July 19). (Figure 4)

The third reason is the big drop in the cost of imports that results from a strong yen. The rising yen largely offset the increase in the cost of crude oil and cut costs for companies that sell imported goods. Benefits have been great for companies like apparel retailers, convenience stores, miscellaneous goods stores, 100-yen shops, and other stores that are behind Japan’s distribution revolution. These sectors have further lowered their costs significantly by benefiting from the Internet revolution and other advances in technology. Falling prices at these stores have in turn raised the real purchasing power of Japanese households. Shouldn’t we conclude that deflationary pressure in Japan is easing even as the yen appreciates?

The second reason is the increasing resilience of Japan’s exporters to a strong yen. An upturn in the yen no longer produces downward pressure on wages in Japan. Workers that exporters hire in Japan are not the inexperienced, low-paid laborers in countries with which Japan competes. All are technocrats with expertise in engineering, marketing or management. This is why summer bonuses in Japan are up 4.2% from last year despite the strong yen and the recent earthquake and tsunami (Nikkei Shimbun, July 19). (Figure 4)

The third reason is the big drop in the cost of imports that results from a strong yen. The rising yen largely offset the increase in the cost of crude oil and cut costs for companies that sell imported goods. Benefits have been great for companies like apparel retailers, convenience stores, miscellaneous goods stores, 100-yen shops, and other stores that are behind Japan’s distribution revolution. These sectors have further lowered their costs significantly by benefiting from the Internet revolution and other advances in technology. Falling prices at these stores have in turn raised the real purchasing power of Japanese households. Shouldn’t we conclude that deflationary pressure in Japan is easing even as the yen appreciates?