Government bond sales by enemies who find themselves in the same boat

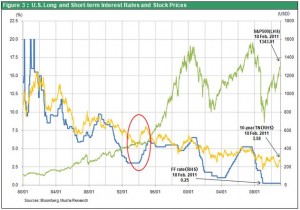

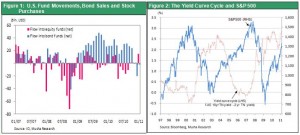

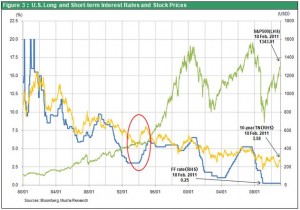

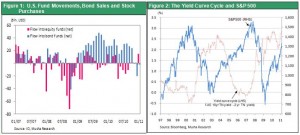

Selling pressure on government bonds has temporarily eased because of geopolitical instability spreading from Egypt to Libya and elsewhere in the Middle East. But we are about to see a veritable tsunami of government bond selling worldwide. Optimists and pessimists alike are in complete agreement that sovereign debt should be sold. There are many reasons. Most significant are fear of rising public-sector debt, concern for inflation, expectations for an economic recovery, and the upcoming end of QE2. There is no doubt that investors are making big changes in their portfolios by eliminating government bonds. The result is a clear shift in supply-demand dynamics. Investors are very confident that they are making the correct decision. Never before has the yield curve (for 10-year and 2-year bonds) been steeper than it is now. This curve shows that expectations of inflation are growing and that investors believe interest rates will start rising.

What will happen after the correction to erase excessive pessimism?

The fundamental force behind these events will be a correction to eliminate excessive pessimism currently factored into the market. In the summer of 2010, investors became overly pessimistic once again. The result was probably risk aversion that went too far. Pessimists expected the U.S. to become entrapped in Japanese-style deflation that would cause long-term stagnation and a further drop in long-term interest rates. But this scenario is no longer plausible. A correction is now taking place to eliminate distortions in prices of stocks and bonds. However, opinions differ on where to invest proceeds from the sale of government bonds. Optimists choose stocks while investors with a negative outlook choose gold, high-yielding emerging country government bonds and high-yielding corporate bonds..

Three scenarios

I think there are three possible scenarios.

1) Stock prices continue to rise because of a sustainable economic recovery and minimal inflation (the Goldilocks scenario)

2) Higher interest rates temporarily disrupt financial markets despite a sustainable economic recovery and rising stock prices

3) The stock market rally ends quickly as budget deficits, inflation, a weak dollar and other problems push U.S. long-term interest rates higher and stop the economic recovery

Musha Research believes that the third scenario is very unlikely to occur in 2011. As I have explained in previous reports, all the pieces are in place for a recovery in U.S. economic fundamentals. Companies are reporting record earnings. Households are cutting spending and boosting savings while benefiting from an end to the downturn in housing prices. The U.S. economy is also backed by the wealth effect produced by the stock market rally. Consumption and jobs are both growing steadily as a result. Many government agencies and research institutes are making big upward revisions in their economic growth forecasts for 2011. The FOMC average (4Q/4Q) has increased from 3.2% three months ago to 3.7% today. The Bloomberg consensus estimate (CY/CY) is 3.2% compared with 2.5% three months ago. And Deutsche Bank (4Q/4Q) raised its forecast from 3.3% to 4.3%.

We may see a 1994-style financial panic again

Next let’s examine the second scenario. In general, a sharp upturn in long-term interest rates is often the reason for an end to stock market rally. Interest rates climb because investors believe the Fed is behind the curve with monetary tightening measures as worries about inflation begin to surface. Viewing this as a harmful increase in interest rates gives investors an excuse to start a downward correction by selling stocks. This brings back memories of the events leading to the end of monetary easing that lasted until 1993. The start of interest rate hikes in February 1994 caused government bond prices to plunge in 1994 (the long-term interest rate surged from 5% to 8%). Skyrocketing interest rates caused both the default of Orange County in California and the currency crisis in Mexico (the so-called “tequila shock” of December 1994). Once the panic subsided, the long-term interest rate pulled back to the 5% level. Stock prices that had been flat for one year started increasing once again. Consequently, the 1994 financial panic had little effect on the real economy. This time as well, financial markets may be severely impacted by the herd behavior of investors triggered by the rapid reversal in their expectations from deflation to inflation.

The risk of panic selling may be greater in Japan than in the United States

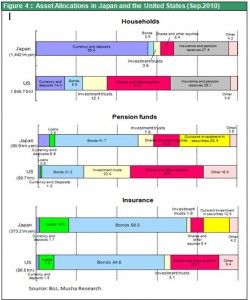

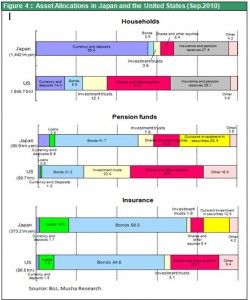

If panic selling starts as investors begin a great escape from government bonds, financial markets in Japan may be impacted more than markets in other countries. There are two reasons. First, there is a general belief that risk avoidance equates to building a portfolio centered on government bonds. But Japan is nothing like the United States in this respect. Table 4 shows a comparison of asset holdings by households, pension funds and insurance companies in the two countries. Bonds and cash and deposits account for a much higher percentage of portfolios in Japan than in the United States. If investors abandon government bonds, the magnitude of the selling in Japan would probably be greater than in the United States. Second, higher U.S. long-term interest rates would probably set a chain reaction in motion that prompts investors to alter their portfolios. Specifically, we could see a big decline in the yen’s strength that ends deflation in Japan, causes investors to resume risk-taking and starts a yen carry trade. Selling pressure on Japanese government bonds is likely to be higher than on U.S. government bonds. This is why investors need to understand that the biggest risk of all is the excessive aversion of risk.

Musha Research believes that the third scenario is very unlikely to occur in 2011. As I have explained in previous reports, all the pieces are in place for a recovery in U.S. economic fundamentals. Companies are reporting record earnings. Households are cutting spending and boosting savings while benefiting from an end to the downturn in housing prices. The U.S. economy is also backed by the wealth effect produced by the stock market rally. Consumption and jobs are both growing steadily as a result. Many government agencies and research institutes are making big upward revisions in their economic growth forecasts for 2011. The FOMC average (4Q/4Q) has increased from 3.2% three months ago to 3.7% today. The Bloomberg consensus estimate (CY/CY) is 3.2% compared with 2.5% three months ago. And Deutsche Bank (4Q/4Q) raised its forecast from 3.3% to 4.3%.

Musha Research believes that the third scenario is very unlikely to occur in 2011. As I have explained in previous reports, all the pieces are in place for a recovery in U.S. economic fundamentals. Companies are reporting record earnings. Households are cutting spending and boosting savings while benefiting from an end to the downturn in housing prices. The U.S. economy is also backed by the wealth effect produced by the stock market rally. Consumption and jobs are both growing steadily as a result. Many government agencies and research institutes are making big upward revisions in their economic growth forecasts for 2011. The FOMC average (4Q/4Q) has increased from 3.2% three months ago to 3.7% today. The Bloomberg consensus estimate (CY/CY) is 3.2% compared with 2.5% three months ago. And Deutsche Bank (4Q/4Q) raised its forecast from 3.3% to 4.3%.