Jul 15, 2024

Strategy Bulletin Vol.358

We cannot overlook the “weak yen is bad” theory

~Do not break the back of Japan's economic revival~

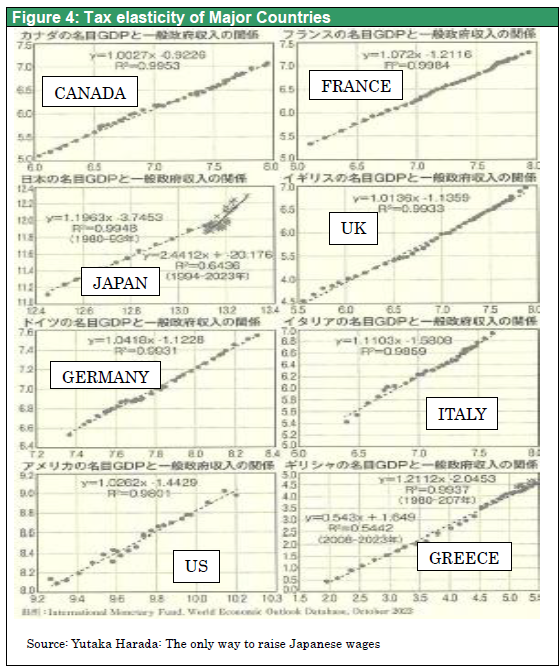

The yen continues to weaken. Consumers, the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry (JCCI) and other business organizations that represent small and medium-sized businesses, as well as many economists, are voicing their concerns and criticisms. Should we view this the “weak yen is bad” theory as a good thing or a terrible thing? The reason we cannot ignore this issue is that it is strongly linked to policy choices and Japan's future directions.

A weak yen is an income transfer from buyers to suppliers, but only temporary

The exchange rate debate is quite simple. It is all about the conflicting effects of a weaker yen: (1) positive for those who export (= those who receive yen and make money) and (2) negative for those who import (= those who pay yen and spend money). But that conflict confuses the situation. Criticism of the weak yen is developed from the standpoint of the latter. The weak yen is a problem because it raises import prices, depriving people of real income. Since 2022, the rise in energy prices associated with the war in Ukraine and the disruption of supply chains caused by the Corona pandemic have triggered global inflation, while in Japan the simultaneous depreciation of the yen has pushed up prices even higher. The government and the BOJ, which had targeted a 2% inflation, were able to achieve their goal, even if only temporarily, but because it was not accompanied by higher wages, workers' real wages fell sharply, depressing consumption. In addition, companies that depend on overseas production and imports saw their import costs rise, putting pressure on their profits. However, these are short-term and transitory negative effects. Price increases will disappear when the yen stops weakening and the year-on-year change becomes zero.

Hard-to-see benefits of a weaker yen

On the other hand, the benefits of a weaker yen, which stand on the former side, appear only gradually and are not uniform. If all companies were simply exporting dollar-denominated goods, the benefits of a weaker yen would be immediately linked to higher profits due to increased sales in yen terms resulting from foreign exchange gains. However, if exporters reduce the price of dollar-denominated exports by taking advantage of the weaker yen, the benefits of a weaker yen will not appear until the company's market share increases (i.e., sales volume increases) due to the price reductions. On the other hand, for companies exporting in yen, the benefits of a weaker yen will not be realized until the export price in yen is raised. For companies that have moved their factories overseas, a weaker yen will increase the cost of imports from overseas factories, which in turn will increase costs. Although there is the benefit of increased value when foreign currency-denominated profits earned by overseas subsidiaries are converted into yen, this benefit will be realized gradually over time. Furthermore, large global corporations, which are most likely to benefit from a weaker yen, do not speak loudly about the benefits of a weaker yen. Thus, while the disadvantages of a weak yen are clear, the advantages are extremely vague and difficult to see. This is why the “weak yen is bad” theory tends to prevail in the media and in the economic discourse.

A weak yen attracts global demand to Japan

The most essential truth, however, is that demand, like water, leaves expensive areas and concentrates in cheap areas. The depreciation of the yen has made Japan's labor costs, land, agricultural products, and factory products significantly cheaper, making companies in Japan significantly more price competitive. Companies that once moved their factories to cheaper overseas locations are beginning to bring them back to Japan. Whether entrepreneurs or individual tourists, consumers of products around the world are flocking to Japan for cheaper prices, boosting domestic demand in Japan. This movement will increase capital investment, production, employment, and wages, creating a virtuous economic cycle.

Economists ignorant of the volume growth and inflationary pressures caused by the weak yen

Even highly respected economists are often ignorant of two basics of exchange rate economics. The first is the J-curve effect. In the initial stages of the yen's depreciation, the negative effect of a decline in real income becomes apparent all at once. However, as time passes, the negative effects disappear, and a virtuous cycle of growth in production volume, capital investment, productivity growth, and wage growth continue over the long term. The second ignorance is that exchange rates do not reflect the real economy but cause it to shape future competitive conditions and the international division of labor. The United States, as the hegemonic power, induced the super-strong yen to weaken Japan, which had been extremely competitive 30 years ago, and as intended, the Japanese high-tech industry, which had been so strong, declined, and the industrial cluster in Japan moved to East Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, and China. As Japan became the world's most expensive country, factories, jobs, and capital flowed out of the country, hollowing out Japanese industry. In addition, wages and land prices, which had become abnormally high by world standards, came under enormous downward pressure, entrenching long-term deflation.

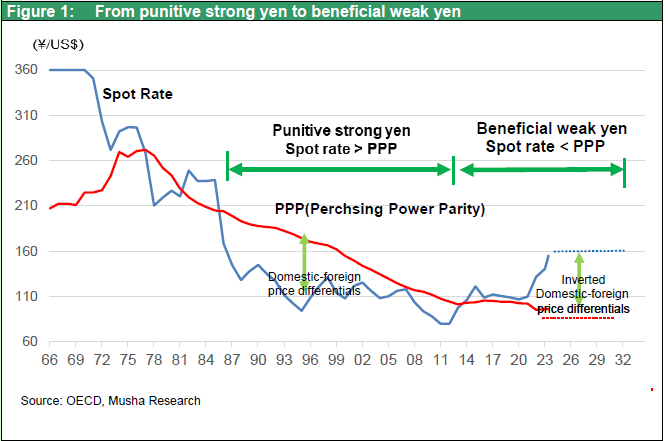

The weak yen has already created a huge pool of purchasing power (corporate profits and tax revenues have surged).

The ongoing depreciation of the yen, contrary to the past 30 years, will cause Japanese companies to become more competitive and provide the basis for Japan's resurgence as an industrial powerhouse. The weak yen and inflation (i.e., higher nominal economic growth) have already boosted corporate profits, stock prices, and tax revenues significantly: corporate recuring income in FY2023 recorded 108 trillion yen (2.5 times higher than 10 years ago), tax revenues 72.1 trillion yen (1.6 times higher than 10 years ago), accumulated investment gain of the GPIF 153.8 trillion yen (4.3 times higher than 10 years ago), and TSE equity capitalization of ¥1004 trillion (3.3 times that of 10 years ago). This has led to record capital investment growth expected in 2023 and a 5.08% wage increase for the first time in 34 years, creating a huge pool of purchasing power. It is almost clear that Japan is entering an era of higher potential growth, a rarity among advanced economies. The "weak yen is bad” theory will be completely debunked by the facts.

Increased tax revenues from a weaker yen should be passed on to consumers

Certainly, at this point, there is a need to bail out individuals who continue to suffer the disadvantages of the weak yen and have not yet entered the wave of prosperity, but the prescription is clear. The public finances enriched by inflation should return money to the people whose wealth has been stolen by inflation in the form of permanent tax cuts.

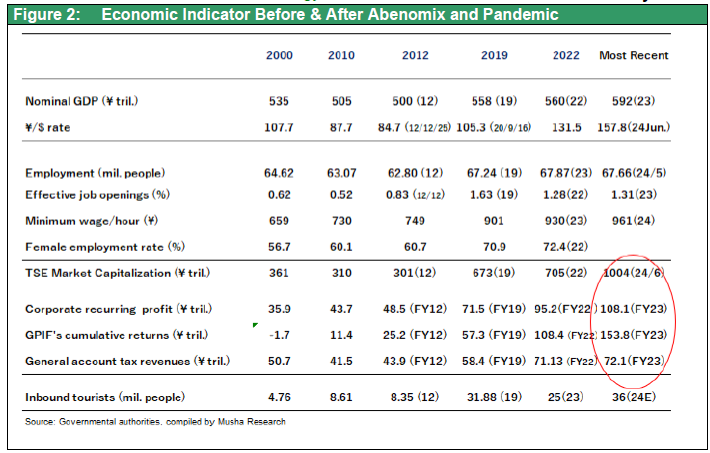

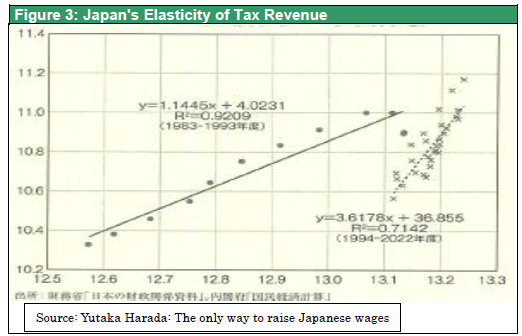

The elasticity of tax revenue, which indicates how much tax revenue grows compare with the nominal economic growth, is abnormally high in Japan, ranging from 2.6 to 3.6 whereas ordinary country ranging 1.0 to 1.2. This is because Japan has continued to raise taxes in real terms by increasing the consumption tax and social insurance premiums. This is discussed in detail in Yutaka Harada's recent book, "The Only Way to Raise Japanese Wages" (PHP Research Institute).

This is why tax revenues have increased significantly due to the inflation that has unexpectedly occurred. The Ministry of Finance has been busy trying to hide the increase in tax revenues, since it is now likely to be able to achieve a primary balance surplus in FY2025 without raising taxes. Multiplying the 5.7% increase in nominal GDP by the tax revenue elasticity of Mr. Harada's calculation yields a tax revenue increase of 10 trillion yen, even using the lower limit of 2.6. It is believed that technical factors that reduce tax revenues, such as changes in the tax payment method for consolidated companies, have been developed to suppress surface tax revenues. The budget surplus has increased due to unspent budget funds and increased tax revenues, which resulted in increase the Government Debt Consolidation Fund.

Furthermore, in addition to increased inflationary tax revenues, the government has tens of trillions of yen in foreign exchange gains from its $1.2 trillion holdings of U.S. government bonds, which are stored as "reserves. The depreciation of the yen and inflation have made Japan's fiscal policy remarkably powerful.

The Hidden Cause of the Weakening Yen: Fiscal Austerity

The dollar/yen rate is expected to peak around 160 yen due to the narrowing Japan-U.S. interest rate differential and Japan's growing current account surplus. If the yen weakens and overshoots its peak, the government could launch a policy mix of massive fiscal stimulus and monetary tightening, which would quickly turn the yen's trend to appreciation. There is no need to worry about the yen weakening.

Based on the economic hypothesis (Mandel-Fleming Model) that expansionary fiscal policy and tight monetary policy lead to a strong currency, while a tight fiscal policy and loose monetary policy lead to a weak currency, the US has a typical strong currency policy mix and Japan has a typical weak currency policy mix. Japan, with its strong hidden fiscal power, can easily stop the depreciation of its currency by creating a high-pressure economy through fiscal stimulus.