Jun 23, 2024

Strategy Bulletin Vol.356

An Analysis of the Inevitability of the "Japan Decline with China Rise to Japan Rise with China “(1)

~The Japanese Revival from the Collapse of the Bubble Economy and Lessons for China~

The Japanese economy is once again on a long-term recovery path after a period of rapid postwar growth, the bursting of the bubble economy, and prolonged economic stagnation. On May 25, 2024, at the annual academic conference of the Center for Industrial development and Environmental Governance (CIDEG) at Tsinghua University, we delivered a keynote report on "Japan's Economic Revival and Lessons for China" under the theme of "A comparative Study of Chinese and Japanese Economic Policies. "

The following is a detailed explanation based on the report. The first is that Japan's economy is now on a long-term recovery path and that two factors have contributed to the prolonged stagnation. The prolonged economic stagnation was caused by external pressure (pressure from the U.S. and the strong yen) and policy errors. Second, there are three similarities between Japan's past and China's present. Third, there are four differences between Japan and China. A comparative analysis of Japan and China reveals that there are common circumstances behind the post-World War II development and setbacks in both countries. Such an understanding is essential when considering policy choices and prospects for Japan and China.

(1) Japan's Entry into the Era of Great Growth (this issue)

(2) Three Similarities between Japan and China that relates US Debt (next issue)

(3) Four differences between Japan and China: Japanese reform and Chinese postponement (next issue)

(4) Conclusion (next issue)

(1) Japan's entry into the Great Growth Era is almost certain

It is almost clear that Japan has emerged from its prolonged economic stagnation and is entering an era of great recovery. This is confirmed by the strong rise in stock prices, the earliest leading indicator of economic trends in the capitalist economy.

Japanese Companies' Great Revival of Earning Power

Leading this recovery is corporate earnings. True corporate earnings, after deducting extraordinary losses such as write-offs of nonperforming loans, can be measured by tax-reported income by companies. Corporate earnings peaked at 43 trillion yen in FY1990 and declined sharply to 2 trillion yen in FY 2000, one-twentieth of the peak, but are expected to grow rapidly to 50 trillion yen in FY2022 and 57.5 trillion yen in FY2023 (estimates by Musha Research). Value creation in the corporate sector is the engine that drives the economy forward, and the robustness of this engine brightens the outlook for the Japanese economy.

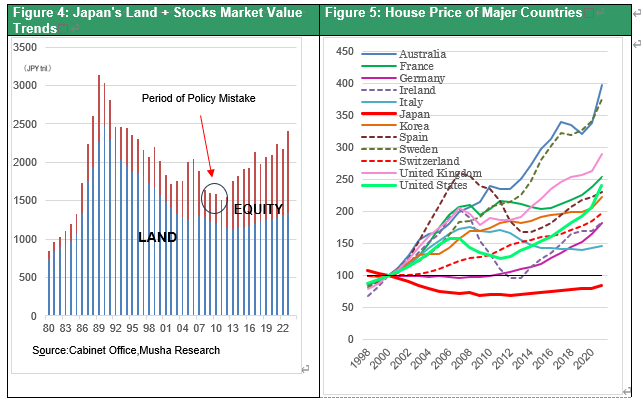

Figure 1 provides an overview of the five indicators, showing that corporate profits are recovering and expanding strongly and quickly, along with stock prices, while labor wages (=employment income) and land prices are recovering more slowly. The trickle-down effect of strong corporate profits is likely to cause an expansion of wages, consumption, and capital investment.

Figure 1: Trends in stock prices, land prices, corporate income, household financial assets, and employment income (1980-2023)

Initiative corporate efforts, a major shift in business models and improved corporate governance

The revival of Japanese corporate profits has been supported by two factors: (1) the efforts of Japanese companies and proactive conditions such as the government's reform policies, and (2) improvements in the external environment, including a very weak yen and a semiconductor boom brought about by the US desire to strengthen its supply capacity in Japan as a result of the US-China conflict. Japanese corporate profits were plunged to5% from previous peak by the U.S.'s aggressive attack on Japan, the super-strong yen, and the profligate management of Japanese companies that sat on their bubbles, but they have made a remarkable comeback. In response to the strong yen, they shifted their factories overseas. It also took advantage of the strong yen to acquire overseas companies and transformed itself into a global player. Furthermore, the company cut costs in Japan through restructuring, mechanization, and labor cost reductions. In addition, the company thoroughly revised and restructured its business model, including concentration and selection.

Furthermore, corporate governance reforms as part of Abenomics have progressed since around 2015, and the pursuit of return on capital over cost of capital, a capitalist merkmal as a compass for corporate management, has taken root and financial efficiency has improved significantly.

The U.S.-China Conflict and the Great Turn toward a Weaker Yen

The most important change in external conditions was the sharp turn in the U.S. attitude toward Japan. Since mid-1980’just before the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has begun to attack Japan, which is considered a threat to The U.S. because of significant strengthened industrial competitiveness and outpacing U.S. firms in key industries such as semiconductors, electronics, and automobiles. Trade friction and the super-strong yen became the means to this end. For example, in the Japan-U.S. semiconductor agreement, the U.S. demanded that Japanese companies deviate from trade rules by allocating 20% of all semiconductor purchases to U.S. products, and Japan had no choice but to comply. The Japanese yen was permanently raised above purchasing power parity, the currency's real strength, by more than 30% between 1900 and 2010, and by twice as much at its peak in 1995, severely undermining the cost competitiveness of Japanese firms. Industrial clusters of high-tech manufacturing industries that had been concentrated in Japan shifted to South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. Observing Japan's industrial competitiveness in terms of global semiconductor production share shows that Japan, which accounted for 50% of the global semiconductor market in 1990, has declined to less than 10% since 2013. The strong yen had made the Japanese companies’ cost the most expensive in the world. Factories, jobs, and capital have been moving out of Japan due to higher costs, which hollowed out the Japanese economy. Also, they have been holding down wages, making Japan the only country in the world where real wages have remained flat for 30 years, and deflation has taken hold.

A weak yen combination with strong profits and labor shortages leads to sustained wage growth

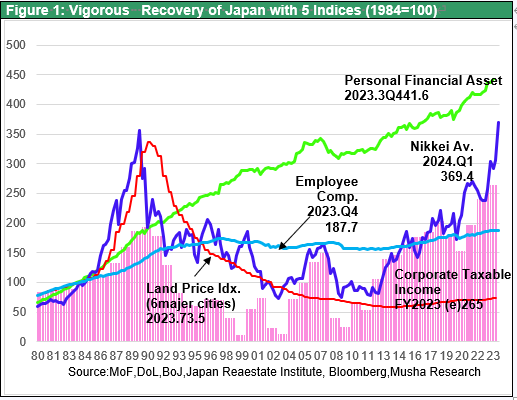

However, the U.S.-China confrontation became decisive in 2018, and the U.S. desire to restructure its supply chain, which is concentrated in China, has steered the country toward acceptance of significant yen depreciation. The dollar-yen rate remained between 100 and 110 yen per dollar until early 2022 but has since fallen all the way to the 150-yen level. That is nearly 40% below purchasing power parity, which has significantly strengthened the price competitiveness of Japanese companies. Demand has begun to concentrate toward Japan, which has become a remarkably low-cost country in the world. A virtuous cycle began to emerge, with factories returning to Japan, exports increasing, and overseas tourists increasing (Figure 2). Furthermore, wages in Japan have fallen to levels not seen in developed countries, which has increased the pressure to raise wages. The conditions for wage increases are now in place: the unemployment rate is at full employment at 2.6%, corporate profits are unprecedented, and Japanese companies must stop the departure of their best personnel. The 2024 wage hike rate is 5.08%, the highest level in 33 years. In March, the BOJ lifted all of its negative interest rates, yield curve control (YCC), and other forms of monetary easing. It is clear from the above that Japan's economy is almost out of deflation and prolonged stagnation.

Figure 2 Purchasing Power Parity and the Dollar/Yen Rate

Going forward, the Japanese economy is expected to enter a period of higher potential growth, which is rare among advanced economies, because of the synergistic effects of the initiative-taking conditions and favorable external environment.

Abnormally Undervalued Japanese Stocks = Negative Bubble Still Continues

Japanese stock prices are severely undervalued and are likely to rise further in the future. The purest and most accurate measure of stock prices is the comparison with the yield on government bonds, and Japanese equities are currently offering significantly higher returns than government bonds, yielding 6% on equities and 1% on government bonds. While they are currently significantly undervalued, in 1990 stock prices were significantly overvalued with less than 2% of earnings yield and 8% government bond yield.

Irrational investment attitudes are changing now

However, the asset allocation of Japanese households is irrational. A comparison of the allocation of household financial assets between Japan and the U.S. reveals Japan's marked dependence on deposits. In Japan, 73% of financial assets, excluding pension insurance, are in bank deposit with almost zero interest. On the other hand, stocks, and investment trusts, which return 2% from dividends alone and 6% if retained earnings are included, account for only 20% of total financial assets. In the U.S., stocks and investment trusts account for 72%, while cash and deposits account for 18%, exactly the opposite composition, indicating that U.S. households have continued to build large assets thanks to the stock market appreciation. The net worth of U.S. households has grown from $59 trillion in 2009, immediately after the GFC, to $156 trillion by the end of 2023, a massive $97 trillion (3.5 times GDP) in 14 years, which has led to robust consumption. In Japan, the Kishida administration's expansion of tax breaks for individual stock investment (NISA reform) will trigger a major shift of funds from cash and deposits to stock and investment trusts, which accelerates the stock market rally.

The "new capitalism" will make U.S.-style equity capitalism take root in Japan as well

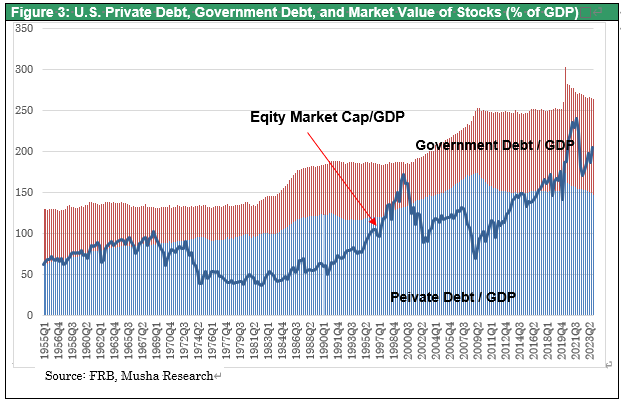

The anticipated rise in Japanese stocks suggests that Japan is heading toward an era of U.S.-style stock market capitalism. In the U.S., we are entering an era of equity capitalism in which rising stock prices are the primary driver of economic expansion. Figure 3 shows the trends of the three major drivers of the U.S. economy: private credit, public credit, and equity credit (= market capitalization). In other words, there was no new credit creation in the banking sector. This was complemented by a remarkable rise in stock prices and the ratio of stock prices to GDP. The stock/GDP ratio (the so-called Buffett index) rose from 69% in 2009 to 205% by the end of 2023. In other words, the means of credit = demand creation has shifted to stocks. On the other hand, U.S. companies are now returning almost 80% of their earnings to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks, and a new money flow has taken root. This is a complete change from the pattern of the past, when households' savings surpluses were absorbed by banks deposits, which in turn became bank loans, thereby circulating money. The corporate return to shareholders raises stock prices and increase households' asset income (price gains + dividend income) Which support household consumption. This has currently emerged new system as US equity capitalism.

In Japan, corporate governance reforms and demands by the government and the TSE for correction of companies with low capital efficiency are driving share buybacks and dividend increases. Japan's shareholders return ratio, which is now only 40%, will probably increase to 50-60%. In this way, Japan may enter the era of equity capitalism, in which rising stock prices will support the economy.

Figure 3: U.S. Private Debt, Government Debt, and Market Value of Stocks (% of GDP)

Policy Mistakes that Prolonged Deflation and Stagnation

It is necessary here to mention one more reason for Japan's prolonged stagnation: policy errors. The first of these is the postponement of problem-solving. From 1990, when the bubble economy burst, until 1997, the government, corporations, and financial institutions covered up the problems, shifted the blame, and took fiscal levers to cover the problems, instead of taking painful and essential measures to solve them.

In 1997, the crisis of financial institution failures finally triggered painful financial structural reforms, and public capital was injected into the banks as compensation for the reforms, and the government and the Bank of Japan took over the bad loans. The public funds injected into the banks were fully repaid now except for SBI Shinsei Bank and two regional banks.

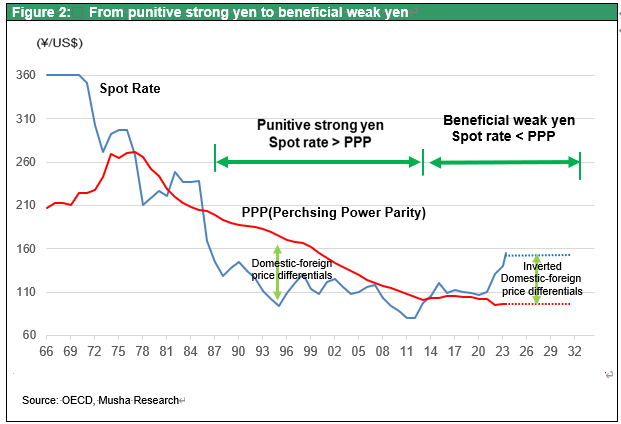

The Japanese economy began to recover after 2003, but this is where the second mistake occurred. This was a premature shift to monetary and fiscal tightening. Unfortunately, the GFC coincided with this, and the Japanese economy hit a "W" bottom. The GFC was a financial crisis in the U.S. and other countries. However, Japan, which was the furthest away from the epicenter of the crisis, suffered the greatest economic impact, and its stock prices slumped the longest. Premature policy tightening pushed stock and real estate prices down beyond their intrinsic values, imposing additional costs on companies and plunging Japan's recovering economy and stock prices to a "W" bottom. The total market value of Japan's national wealth, including land and stocks, peaked at 3,142 trillion yen at the end of 1989 and bottomed out at 1,723 trillion yen at the end of 2002, but fell further after the GFC to 1,512 trillion yen at the end of 2011 (and has recovered remarkably to 2,410 trillion yen at the end of 2023). This double-dip recession could have been avoided if the right policies had been taken. It is likely to be a lesson for China.

Figure 4: Japan's Land + Stocks Market Value Trends

Figure 5: Hpuse Price of Majer Countries