Aug 07, 2023

Strategy Bulletin Vol.337

Significance of BOJ's YCC Policy Change

~ Increased confidence in the BOJ's ability to carry out its policy

(1) BOJ heading for YCC exit

Long-term interest rates will be left to the market and rise

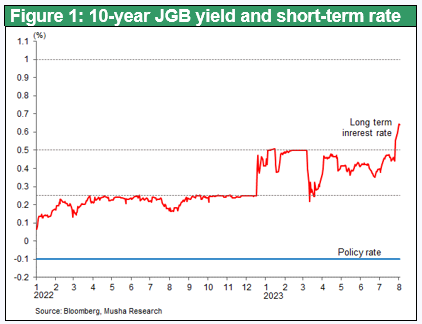

On July 28, the BOJ announced changes to its yield curve control (YCC) policy. This is the second YCC change since last December. Interest rates include short-term rates determined by policy and long-term rates determined by the market, but the YCC introduced in 2016 was designed to allow the authorities to control long-term rates, which are originally determined by the market. Since then, the upper limit on the yield on 10-year JGBs allowed by the BOJ has been 0.25%, but this was raised to 0.5% with the change last December.

This time, it was raised further to 1.0%. This increase in the market's discretionary latitude is no doubt a step toward the exit from the YCC, no matter how the BOJ may explain it. Since last December, the yield on the 10-year JGB has shifted from below 0.25% to a range of 0.4-0.5%, but this decision is expected to raise the level further. It has risen to 0.65% in the week since the policy change and is expected to remain between 0.5% and 1.0% going forward, depending on the BOJ's operations.

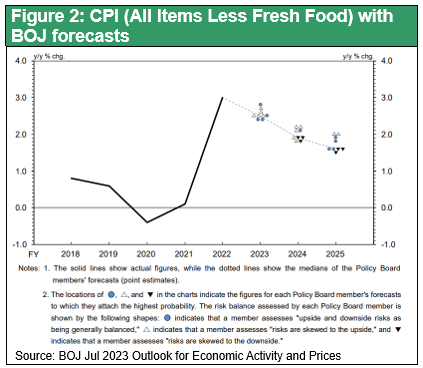

Not negative for stock prices or risk taking

While the assessment has been made that this is an obvious rate hike and therefore a turn toward tighter monetary policy, which would be negative for stock prices and risk-taking, this would not be correct. First, the change is positive because it brings the Bank of Japan closer to its target of 2% inflation, i.e., closer to a more desirable economic condition. Second, the CPI surge has caused real interest rates to fall sharply, which will reinforce the effects of monetary easing. The BOJ's median CPI forecast excluding food and energy prices is 3.2% for FY2023, 1.8 percentage points higher than the forecast made a year ago, which means that even with this rate hike, real interest rates will fall. The Nikkei Stock Average fell 3% or about 1,000 points after the policy change (partly due to the downgrade of the U.S. government bond rating), but we expect it to settle down sooner or later.

YCC's exit is in sight

Nevertheless, the YCC, in which the BOJ controls long-term interest rates, which are originally determined by the market, is not a monetary policy that can be continued indefinitely. It was a bizarre policy in response to the extraordinary situation in which long-term interest rates fell into negative territory, and it is a policy that should be stopped when the situation changes. Now that the risks of deflation and lower interest rates have disappeared and the economic market environment has shifted to inflation and higher interest rates, it is necessary to change the YCC framework. The side effects of the YCC itself have been small so far, and there is no problem in sustaining it. However, once the market decides that the BOJ has fallen behind in its efforts to counter inflationary pressures and the yen's depreciation, the market could be thrown into turmoil by intense speculative selling of JGBs and the yen. Before this happens, the BOJ must modify its monetary policy ahead of market expectations. The revisions to the YCC in December of last year and July of this year can be considered as a well-prepared guide to exit.

(2) YCC as a creative monetary policy development by central banks

Recent global central bank monetary policy has been full of creative policy developments in response to new realities, and YCC must be evaluated in this context.

The creativity and splendid results of quantitative monetary easing

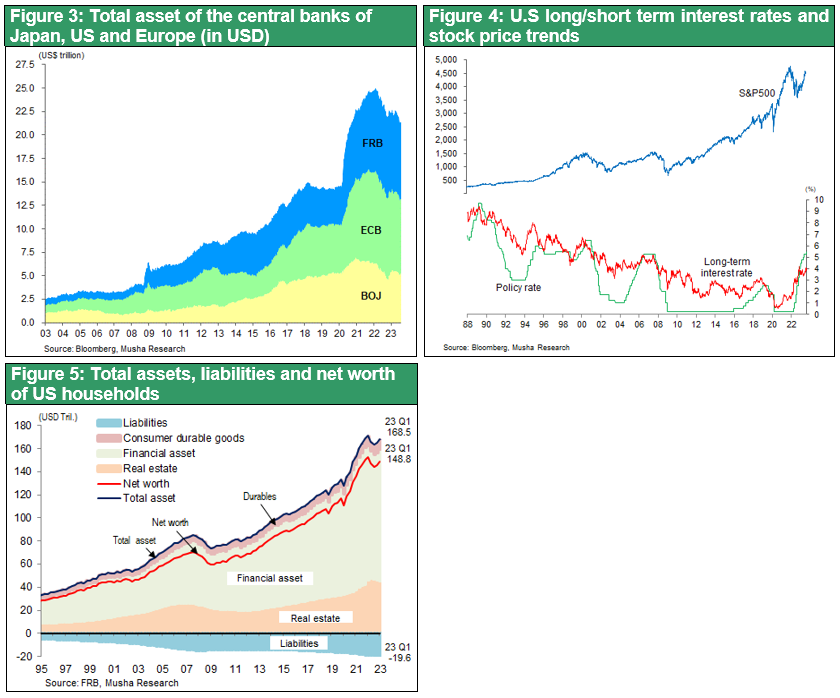

In the past, interest rate policy was the mainstay of monetary policy, but with short-term interest rates stuck at zero following the GFC, and the weight of credit creation through bank lending declining, a new policy tool became necessary, and Quantitative Monetary Easing was introduced. Under Chairman Bernanke, the U.S. Fed implemented three rounds of quantitative easing, expanding total assets by 5.5 times, from $800 billion to $4.5 trillion.

This boosted asset prices, which had been plummeting, and had a tremendous economic impact. U.S. stock prices soared fourfold over the next decade, real estate prices rose, and the net worth of U.S. households doubled from $50 trillion to $100 trillion. This enormous increase in household assets, equivalent to 2.5 times the U.S. GDP, boosted U.S. consumption, which became the driving force behind the sustained economic expansion.

Simply put, the new policy of increasing aggregate demand by injecting money into the asset market by the central bank to push up asset prices has taken root. The spillover channel (transmission mechanism) of monetary policy has clearly shifted from the traditional control of bank lending to the control of asset prices.

Success of Kuroda’s quantitative and qualitative monetary easing and difficulties in 2016

In Japan, following the formation of the second Abe administration, Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda embarked on ultra-aggressive quantitative monetary easing similar to the U.S. in April 2013 under the banner of "Different-Dimensional Monetary Easing. The original plan to double the monetary base in two years through purchases of long-term government bonds and equity ETFs was further strengthened in January 2015, increasing the pace of annual monetary base expansion from 60-70 trillion yen to 80 trillion yen.

As in the U.S., the power of this program was immense, with stock prices doubling in two years, the dollar plummeting from ¥80 to ¥120, and prices emerging as positive.

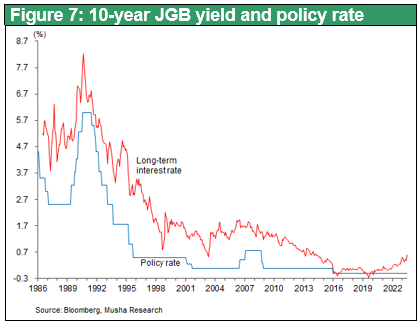

However, the consumption tax hike from 5% to 8% in 2014 and the global economic slowdown and rising deflationary pressure caused by the China shock in 2015 brought long-term interest rates to fall sharply worldwide, and at one point more than 30% of long-term government bond yields worldwide fell into negative territory. Long-term interest rates in Japan also fell below 0% in 2016. Banks operate by raising funds at short-term interest rates and investing them at long-term interest rates, earning a profit with spread of both, so when long-term interest rates go negative, they cannot operate. The YCC (yield curve control) introduced in September 2016 was a desperate measure to rescue the banks. By fixing short-term interest rates to negative (-0.1%) and the yield on 10-year government bonds to positive (0 to 0.25%), the banks' interest margins were secured. Here is where the problem arose. In order to push up negative long-term interest rates, the brakes must be applied to quantitative easing and JGB purchases must be reduced. If the market sees this as a retreat from monetary easing, the yen could soar, exacerbating deflation.

YCC as a modification of quantitative monetary easing

As a desperate measure, the BOJ shifted its monetary easing tools back to interest rate policy and took steps to ensure that a reduction in quantitative easing would not lead to a stronger yen. Kazuo Monma, an executive economist at Mizuho Research who was involved in policy as a BOJ board member until 2016, explains that the new monetary easing policy framework was truly YCC. In 2016, there were many economists, including Musha Research, who were suspicious that the BOJ was breaking the pace of asset growth, but no one claimed that this was a setback for quantitative easing. The BOJ's much-publicized YCC as a new dimension of monetary easing was a distraction. Thus, the BOJ's decision to refrain from asset purchases was not perceived as putting pressure on the yen to appreciate.

Proof of the BOJ's policy implementation capacity

The YCC, which was born from this process, has almost completed its historical role now that long-term interest rates have become permanently positive and, in fact, upward pressure is intensifying. The two YCC changes as a carefully prepared and orderly exit guide showed that the BOJ was fully capable of handling the situation. In 1992, the Bank of England in the UK was forced to leave the ERM (European Exchange Rate Mechanism) after losing out to George Soros' speculation. At that time, the Bank of England was forced into a dichotomous situation of cutting interest rates to stimulate the economy and maintaining a strong currency as required by the ERM, but no such dilemma exists today at the Bank of Japan.

Criticisms of the BOJ's different -dimensional monetary easing and YCC include (1) it will keep zombies alive, (2) it will weaken fiscal discipline, (3) it will create asset bubbles, (4) it will cause the yen to collapse, etc., but these criticisms are mostly false accusation and not at all serious ones. We would like to add that these are not at all dire and will not hinder the BOJ's policy implementation in the immediate future.