Oct 25, 2022

Strategy Bulletin Vol.316

The yen’s sharp fall will unravel the 'deflationary equilibrium'

The storm of a weakening yen is likely to trigger a return to a prosperous Japan.

- The stubborn stability of zero nominal growth, zero price inflation and zero interest rates ('deflationary equilibrium') continued because of the ongoing capital leakage (i.e., leakage of business opportunities) from Japan.

- The super depreciation of the yen will enforce the repatriation of Japanese capital sitting abroad that had been hoarded in a way that did not contribute at all to the Japanese economy, This would trigger the collapse of Japan's firmly entrenched zero, zero, zero "deflationary equilibrium".

- This is a phase that strongly requires the conceptual skills of policy makers.

(Note) To be more precise, the GDP deflator continued to decline from 1998 to 2013, but has been rising since then, so strictly speaking, we cannot say that the economy was in a "deflationary equilibrium" after 2013. However, the equilibrium state continued after 2013, with almost zero nominal economic growth, zero CPI, and zero interest rates, except for the impact of the consumption tax hike. In this report, we refer to the "zero-zero equilibrium" that has persisted since 2013 as the "deflationary equilibrium.

(1) The 'deflationary equilibrium' that solidified the three lost decades

Why did deflation bring long-term stability?

Deflation is not inherently equilibrium. Deflation is what stops capital from transforming its value form in search of growth and forces it to remain in money. Therefore, it inevitably leads to a spiral of economic contraction, as in the Great Depression, etc. This was the conventional wisdom in economics until around 2000. In Japan, however, a strong 'deflationary equilibrium' - economic stability under deflation - has long been entrenched. Even during deflation, there was very mild real growth and the people's lives were spared catastrophe. Also, in Japan, phenomena such as the growth-driven widening of inequality, social fragmentation due to the fall of the middle class and the rise of populism, as in Europe and the US, are not so pronounced at present. This has led to the spread of stagnation-affirming ideas, such as the "idea of descent" and the "de-growth steady-state society", which argue that there is no need to pursue growth.

Why did zero nominal growth, zero interest rates and zero inflation become entrenched?

The robust stability of zero nominal growth, zero price inflation and zero interest rates that has taken hold in Japan is considered to be the reality of a 'deflationary equilibrium'. The purpose of this report is to argue that this robust "deflationary equilibrium" may be about to collapse due to the sharp fall in the yen.

Why, in the midst of global growth, has stagnation, akin to that of a medieval agrarian society without technological development, persisted for so long and so firmly in Japan alone? In Japan, too, the digital net revolution, which has driven global growth since 2000, has progressed and labor productivity has clearly increased. In addition, due to globalization, there was also a source of income, as in the West, from the use of low-paid labor overseas. Against this background, why did Japan remain in such a state of persistent stagnation?

(2) The massive outflow of capital and the overseas shift of companies that fixed the deflationary equilibrium

Even in a "deflationary equilibrium", productivity rose, profits increased and stock prices rose

On closer inspection, not all of Japan was stagnant. Per capita labor productivity was rising. Corporate profits increased markedly. Share prices also rose significantly from 2013 onwards. Despite this, let us consider for the moment that the stubborn stability of zero nominal growth, zero price inflation and zero interest rates continued because of the ongoing capital leakage (i.e., leakage of business opportunities) from Japan.

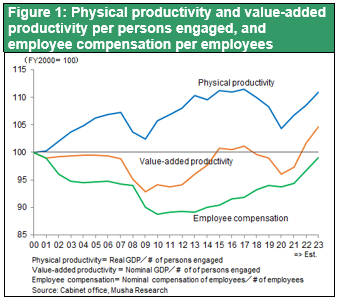

Figure 1 shows the trends in corporate physical productivity, value-added productivity and labor compensation. Despite the growth of physical productivity, the strong yen and falling sales prices due to deflation have meant that companies have not been able to reap the fruits of productivity growth and value-added productivity has remained flat. However, the link is clear: labor remuneration was further restrained, thereby ensuring corporate profits.

Corporations, banks and institutional investors have all channeled their savings into overseas investment

Japanese companies responded to the strong yen and evaporating domestic demand by relocating production overseas and expanding overseas operations. They were able to continue to grow by expanding overseas investment, increasing their dependence on overseas income and reinvesting increased consolidated earnings abroad. Companies, on the other hand, curbed domestic investment and reduced their financial leverage.

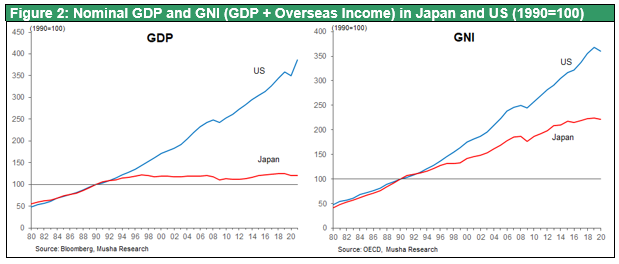

Figure 2 shows that nominal GDP (domestic value creation) was completely stagnant in Japan , but GNI, which is the addition of overseas income, grew, although not as fast as in the US.

Japan became a 'rentier state' like the British Empire

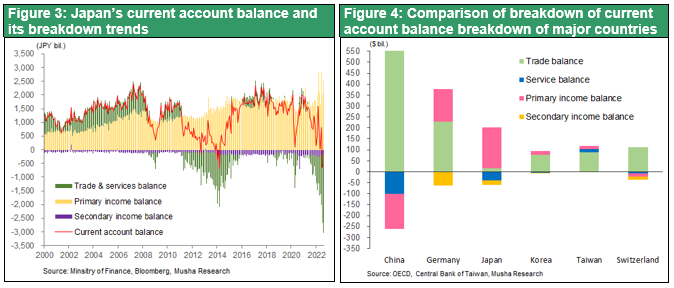

Japanese companies have rapidly expanded their overseas business, first in response to the strong yen and later in search of demand growth. As a result, Japan has changed from a country that earns money from trade to one that earns money from overseas investment, as can be clearly seen in Figure 3, which shows the breakdown of Japan's current account balance. The extremely heterogeneous income composition of this dependence on foreign investment earnings is evident from the comparison of countries in Figure 4. All countries with current account surpluses except Japan earn their income from trade.

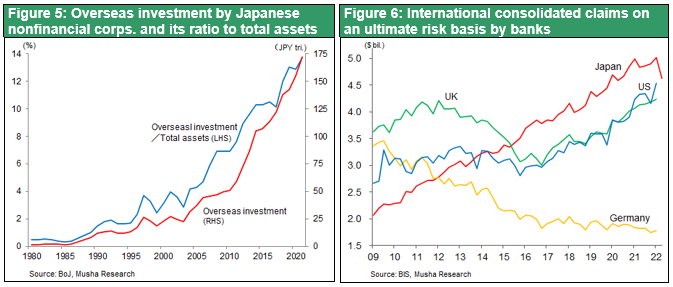

This rapid increase in foreign investment is clearly shown in Figure 5. The balance of overseas investment by companies has risen sharply from 25 trillion yen in 2004 to 170 trillion yen in 2020. Even under stagnant Japan, corporate income continued to rise and capital continued to accumulate, but it flowed overseas in search of higher returns.

Japanese financial institutions also sharply increased their investments and loans abroad. Since the GFC, Japanese banks' foreign loans have increased from USD 2 trillion in 2009 to USD 5 trillion in 2021, a remarkable increase of USD 3 trillion (400 trillion yen) in just over a decade. It also meant that a huge amount of national wealth was leaked overseas. It should be noted, however, that the increase in foreign investment and loans did not all come from domestic sources, as Japanese banks simultaneously increased their foreign currency-denominated short-term funding and create long-term lending positions.

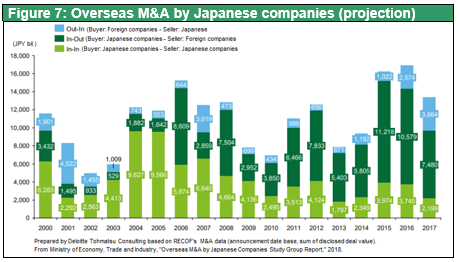

This capital outflow was also accelerated by the acquisition of overseas companies by Japanese companies and the management of foreign currency assets by Japanese investors.

One example of this can be seen in the rapid increase in foreign equity and bond investments by the GPIF: the share of foreign securities, which was only around 15% until 2009, reached 50% in 2021. Many institutional investors, including Japan Post Bank, followed this shift by the GPIF to diversify its portfolio and invest in foreign securities.

Deflationary equilibrium" = leakage of the fruits of technological progress and productivity gains overseas

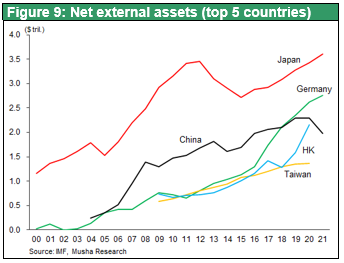

As described above, Japan has been in a state of equilibrium for more than 20 years in which the fruits of technological innovation and productivity growth have not remained in Japan but have leaked overseas. As a result, Japan accumulated foreign investment despite its domestic stagnation and became the world's largest net foreign investment position. Like the British Empire, it has become a country that lives off interest from overseas investment.

(3) Super depreciation of the yen halts capital outflows from Japan and deflationary equilibrium collapses

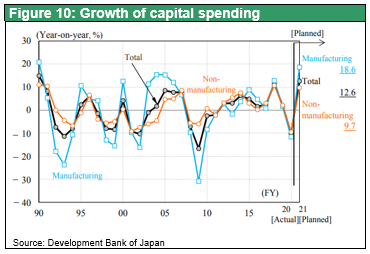

Record growth in domestic capital investment

This mechanism of constant capital outflow may come to an end with a sharp fall in the yen. First, the focus of corporate investment is shifting from overseas to domestic. In September, the Bank of Japan's Tankan survey showed record growth in capital investment plans for FY2022 of 16.4% for all industries and 21.2% for the manufacturing sector. Construction of TSMC's Kumamoto plant, which will total JPY 1 trillion, has also begun, with the WSJ reporting that TSMC has intentions to build a second, more advanced plant. Other projects worth tens of billions of yen include the first new EV production building at Subaru's Oizumi plant in 60 years, the restart of Renesas Electronics' Kofu power semiconductor plant, SUMCO's new Imari plant, Sumitomo Metal Mining new Niihama plant for nickel electrode materials, Iris Oyama's partial domestic transfer of plastic production in China, Kyocera's semiconductor Plant in Kagoshima Sendai, Daikin Industries' domestic transfer of its China-dependent supply chain, Canon's first new exposure system plant in Utsunomiya in 21 years, Yaskawa Electric's return to domestic production of key components and construction of its Fukuoka Yukuhashi plant, and Fujifilm's Toyama plant for the production of biopharmaceuticals on a contract basis.

As the depreciation of the yen becomes more clearly established, the return of factories to the domestic market will intensify, and investment growth is bound to increase further. In particular, the system of dependence on Chinese production is rapidly becoming dangerous due to the Sino-American conflict and the strengthening of the Chinese Xi dictatorship.

Institutional investors stand exposed to overseas asset risk

Financial institutions and institutional investors, who have placed overseas investments at the core of their portfolios, are also stuck with the risks of overseas investments. The sharp rise in overseas interest rates (i. e, bond price collapse ) and the yen's sharp fall in addition to falling stock prices have heightened the uncertainty of investing in foreign currency assets. Portfolio investment abroad will probably decrease significantly. Despite the sharp fall in property and housing prices in the US, UK and other overseas markets, global investors are investing actively in Japanese property. This is because they can no longer overlook the undervalued nature of Japanese property. The undervaluation of Japanese asset prices is even more pronounced in Japanese equities, and while Japanese investment in overseas securities is expected to decline, foreign investors are likely to increase their investment in Japanese equities.

Acceleration of Japanese investment due to the establishment of China-free supply chain

The IMF forecasts the global economic growth rate as of October (1.0% in the US, 0.5.% in the Eurozone and 1.6% in Japan) and the OECD as of September (0.5% in the US, 0.3% in the Eurozone and 1.4% in Japan). As (1) the Japanese economy has maintained an easing trend amid global monetary tightening, (2) the economy has suffered the largest decline due to overreaction to the Corona pandemic, but a rebound (revenge consumption etc.) is expected, and (3) the positive effects of a weaker yen are expected to emerge. Global funds will probably gather in Japan, which is the most undervalued country in the world and has high growth expectations for 2023. With the Sino-American conflict rapidly escalating, building a high-tech supply chain out of China has become a pressing issue. The possibility of high-tech industry clusters returning to Japan has increased significantly.

If the government's foreign currency holdings of USD 1.2 trillion in wasted money are diverted to fund domestic investment, the effect will be enormous

In addition, although it may sound like a pipe dream, if the Japanese Government's dollar-selling intervention gets under way, capital inflows will be accelerated by selling US government bonds held by the Foreign Exchange Special Account, which has a total of USD 1.2 trillion (JPY 170 trillion) stashed away. As economist Yoichi Takahashi argues, if this huge amount of money held in vain is sold, a huge surplus fund of 170 trillion yen will be created, consisting of 40-50 trillion yen in realized foreign exchange gains and 120 trillion yen in recovery of the principal amount invested. If this money is invested in high-tech, zero-carbon and infrastructure investment, Japan's technology could quickly become the world's most advanced.

The yen's depreciation will thus trigger the return of huge amounts of Japanese assets held abroad , which had been hoarded in a way that did not contribute to the Japanese economy at all, and will cause the zero, zero, zero "deflationary equilibrium" that has become firmly entrenched in Japan to collapse. This is a phase that strongly demands the conceptual skills of policy makers.

The storm of a weaker yen is likely to trigger a return to a prosperous Japan.