Japanese stocks are number one in 2010

In 2009, Japanese stocks had the worst return in the world. But thus far in 2010, Japanese stocks rank first with a dollar-based return of 5.7%. Can these stocks continue to perform so well? I believe there are excellent prospects for a continuation of this rally because Japan’s economy is no longer held back by deflationary forces fueled by a strong yen.

2010 – A year when the dollar hits bottom and speculators attack the yen?

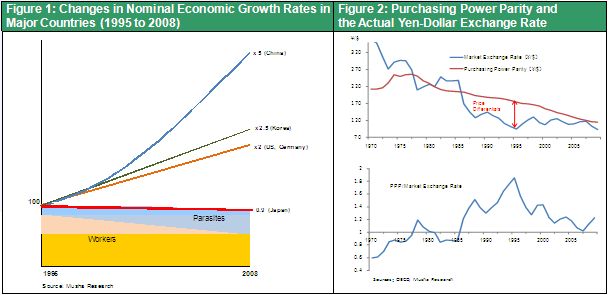

The dollar weakened during 2009 due to the increasing outflow of funds from the U.S. as speculators worldwide procured funds using the dollar at interest rates of almost nothing. But now we are seeing unmistakable signs of a U.S. economic recovery. This is increasing the risks associated with procuring funds in dollars. To replace the dollar, there is an increasing likelihood that speculators will choose the yen. After all, no end is in sight for Japan’s extremely low interest rates because Japan has the poorest prospects for economic growth among industrialized countries. If the yen becomes the preferred currency for the carry trade, the resulting outflows of funds from Japan could produce an unexpectedly large downturn in the yen’s value.

Japanese stocks will quickly catch up with the rest of the world

Japan’s economy suffered the most damage from the financial crisis even though the impact of the crisis in Japan was smaller than in other industrialized nations. The cause was the damage inflicted by a negative cycle driven by a stronger yen and deflation. Industries linked to internal demand and regional economies other than in major metropolitan areas were hurt by declining prices because there is little room for further improvements in productivity. But if see a reversal of the yen in 2010, deflationary pressure will probably diminish significantly as the yen weakens. I think this would bring Japan’s domestic-demand industries back into the limelight. Of course, there is also the possibility of a rapid upturn in Japan’s exports backed by a global economic recovery. A dramatic improvement in earnings of export-dependent manufacturers would appear more quickly. Consequently, for Japanese stocks as well, I believe that 2010 will be a year when investors who aggressively take on risk will be rewarded.

Japan’s lost 20 years, a period of no growth

This beginning of a decline in the yen’s value may signal the end of Japan’s 20-year period of no growth. Deflation linked to the yen’s strength was the heart of the lost 20 years. But deflation should no longer be a problem now that the yen is weakening.

Japan experienced absolutely no nominal economic growth during its lost 20 years because of deflation. As Table 1 shows, during this same period, based on nominal growth, economies in Europe and the U.S. doubled and the Chinese economy expanded by five times. Japan has clearly lagged far behind other regions of the world. Moreover, Japan has seen an enormous shift in income to the “non-working segment of the population” (people receiving pensions and industries in financial trouble) during this period of economic stagnation. As a result, individuals who are producing goods and services have seen their incomes decline. Naturally, the downturn in remuneration for work has caused a decline in the morale of workers and created a widespread feeling that there is no way to end this problem.

The true cause is deflation linked to the yen’s strength

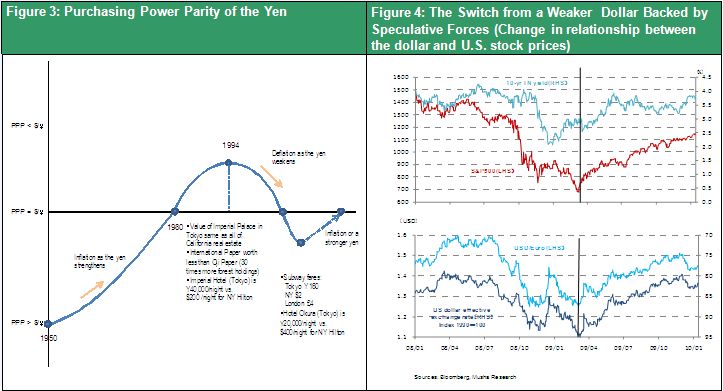

Why has Japan struggled with deflation? Some people blame it on the Bank of Japan. Others believe that a big gap between supply and demand is responsible. I believe the key factor is deflation linked to the yen’s strength. In the early 1990s, the yen became much stronger because of Japan’s highly competitive industries and trade friction with the U.S. Based on purchasing power parity, the dollar was worth about ¥190 at that time. But at one point, the dollar was worth less than ¥100, which equates to a price differential of more than 100% relative to the U.S. In other words, the expenses of companies operating in Japan were twice as high. In response, Japanese companies were forced to cut costs and streamline operations to boost productivity. Under normal conditions, this price differential should be eliminated by a drop in the yen’s value. However, there has been no downturn in the yen during the past two decades. Ultimately, the price gap between Japan and other countries was eliminated by differences in the rate of inflation. This explains why Japan was constantly subjected to such powerful deflationary forces for a period of two decades.

A strong yen is the price of Japan’s “free ride”

The next question is exactly why the yen remained so far out of line relative to purchasing parity power for such a long time. The answer is Japan’s consistently massive trade surpluses fueled by industries that became too competitive for a while. Japan’s “free ride” in the postwar years is a major reason that Japanese companies became so competitive in the 1990s. The U.S. was partly responsible for this “free lunch” by making generous technology transfers to Japanese companies and opening its markets to imports. Consequently, we can interpret the excessive strength of the yen as the price that Japan is finally paying for its “free ride.”

No more need to pay for the “free ride”

The enormous gap between prices in Japan and other countries (expenses increased faster than purchasing power) has at long last been eliminated. Based on 2008 GDP based, purchasing power parity was ¥116 to the dollar. This is about the same as the actual exchange rates of ¥103 in 2008 and ¥117 in 2007. Furthermore, Japanese companies no longer have a big competitive edge due to the emergence of industries in Korea, China and other countries. Japan had been paying the price for its “free ride” for more than 15 years. But with the yen at this level, these payments have finally ended. There is no longer a need for Japan to accept exchange rates that place the yen above its purchasing power parity. This is why I expect to see over the next year or two clear signs that Japan will not be burdened any more by the “endaka penalty.”

Why the market reacted swiftly to Kan’s statement

Following his appointment to replace Hirohisa Fujii as Japan’s Finance Minister, Naoto Kan stated that he would welcome a weaker yen. I think that the changes in economic undercurrents that I just outlined explain why the market reaction was so fast. Starting a reversal that strengthens the dollar and weakens the yen may signal the end of Japan’s deflationary period and revival of the Japanese economy.