Surplus capital and dearth of investment opportunities before and after each crisis

Financial shocks have become the norm. Examples include the bursting of the IT bubble, the subprime loan crisis, the Lehman shock and the recent Greek debt crisis. Before and after these crises we are observing obvious characteristic: a surplus of capital. In 2005, then Fed chairman Alan Greenspan pointed out the conundrum of unusually low long-term interest rates even during monetary tightening and an expanding economy. The cause was the large amount of excess capital. Current Fed chairman Ben Bernanke believes excess capital in turn is caused by a global saving glut. This glut is occurring because of excessive savings in emerging countries, Japan and many other countries other than the United States. People in these countries are saving their money because of the trauma of financial crises, changes in population profiles and many other factors. This surplus of capital is what is exerting downward pressure on U.S. long-term interest rates, according to Mr. Bernanke.

Professor Siegel’s “bond bubble” theory

As prices of assets plummeted in the wake of the subprime loan crisis and Lehman shock, investors ran away from risk and companies deleveraged their balance sheets. These events most likely temporarily eliminated the surplus of capital. But this surplus is emerging again as market conditions began to return to normal. Falling demand produced enormous amounts of savings even at households and companies in the United States, which is a debtor country. Government budget deficits are growing in countries worldwide. But even these deficits are not enough to soak up the massive amount of savings.

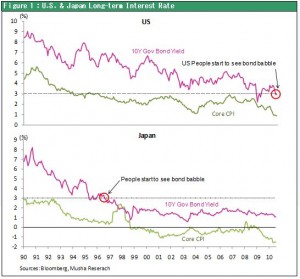

The debt crisis in Greece has sparked fears about sovereign risk that includes the potential collapse of government finances even in major countries like the United States, Britain and Japan. Despite these fears, long-term interest rates have posted significant declines in the United States, Britain and Japan, thus lowering their cost of borrowing. In fact, in The Wall Street Journal on August 19, 2010, there was a column by Wharton School professor Jeremy Siegel titled “The Great American Bond Bubble.”

Higher capital productivity is the cause of surplus capital (our belief)

Let’s examine the causes of the current surplus of capital. (1) Is it the result of excessive monetary easing? (2) Or is a global saving glut the cause, as Fed chairman Bernanke believes? (3) Another possible cause is increasing corporate profitability as the productivity of capital climbs (which is my belief). Excessive monetary easing appears to be widely accepted as the cause. In the past, excessive monetary easing by former Fed chairman Greenspan caused a surplus of capital that, in turn, is regarded as the cause of the subprime loan bubble. The current unprecedented monetary easing in response to the financial crisis is believed to be the source of another surplus of capital. I will analyze this belief another time. However, irrespective of the cause of this surplus, there is no doubt that this surplus will stay for a while.

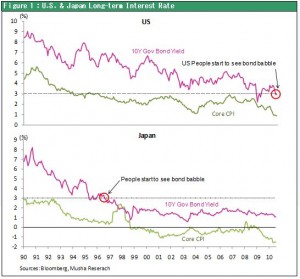

Destination 1: Liquid assets due to extreme risk avoidance (the Japan disease)

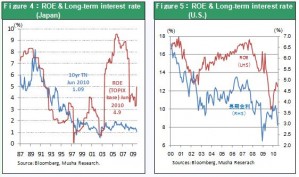

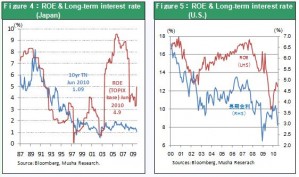

Next, let’s examine how surplus capital is used. There are only three destinations for this money. The first is cash and government bonds as investors shun all forms of risk. Japan followed this path, which resulted in the country’s “lost 20 years.” In 1996, Japanese government bonds were yielding less than 3%. Tiger, Soros and other global hedge funds rushed to sell Japanese government bonds short in the belief that a bubble had formed. But they were very wrong. At a yield of just under 3%, Japanese government bonds were actually an excellent buy because of long-term deflation. Two years later, the yield had dropped to less than 1%.

Destination 2: Excessive capital expenditures

The second destination is capital expenditures, which means buying more unneeded capital equipment even though capacity utilization rates were already low. Investing in more machinery threatens to make the gap between supply and demand even larger. From the standpoint of the real economy, this gap means that deflationary forces will become well entrenched.

Destination 3: Investments in stocks and real estate

The third and only desirable destination is financial assets. Buying these assets raises their prices. As prices of stocks, real estate and other assets climb, there are good prospects for growth in consumer spending because of the wealth effect. As long as surplus capital exists, the government’s only option is to enact policies that encourage people to invest in financial assets (the third destination), thus pushing up the prices of these assets. Chairman Bernanke’s Fed is pursuing a non-traditional monetary policy. I think it is obvious that the Fed’s goal is to raise prices of stocks and other assets by purchasing assets. Chairman Bernanke’s real enemy is the “Japan disease.” Japan fell into an enormous liquidity trap as investors shunned risk and lost their animal spirit.

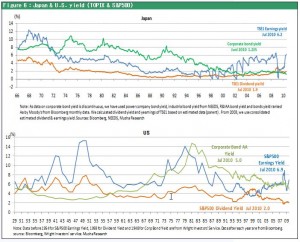

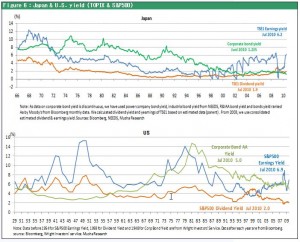

Money is flowing to stocks because of high U.S. earnings and dividends

Fortunately, U.S. stocks are extremely undervalued in terms of their fundamentals. In his August 19 column, Professor Siegel noted that the average dividend yield is 4% for the stocks of 10 large, high-dividend U.S. companies: AT&T, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Proctor & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson, Verizon Communications, Philip Morris, Pfizer, General Electric and Merck. By comparison, the yield on the 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) is three percentage points lower. The yield is more than one percentage point lower on the 10-year Treasury note.

In 1996, earnings of Japanese companies were declining due to failure to restructure operations quickly ? the fundamental difference vs. the U.S.

In 1996, the yield of Japanese government bonds was under 3% and the country was about to enter a period of deflation. But the United States today is completely different in one key respect: strong corporate earnings. In 1996, companies in Japan did not act quickly to stop the constant increase in fixed expenses and enact other restructuring initiatives. Earnings declined as result (and because of the yen’s strength). In contrast, U.S. companies moved fast to restructure operations and boost labor productivity. The result is a sharp rebound in performance that has brought earnings back to almost the all-time high. In 1996, declining long-term interest rates in Japan were linked to deflationary forces throughout the economy and worsening returns on capital. But the decline in U.S. interest rates today is taking place in exactly the opposite environment: improving returns on capital. In other words, unlike Japan in 1996, the United States has an environment that can support higher stock prices for viable reasons.

Japanese stocks are also irrationally underpriced now

Also unlike in 1996, Japan’s long-term interest rate is currently only about 0.9% while corporate earnings are staging a strong recovery (dividend yield 2%, earnings yield 6%, PBR 1). At this level, Japanese stocks are undervalued that there is no rational explanation.