Jun 14, 2018

Strategy Bulletin Vol.200

An age of change on an unprecedented scale

- The rapid emergence of shareholder capitalism

(1) No doubt that an age of unprecedented change has started

The start of the age of unprecedented change

The world has been reshaped by remarkable changes linked to the internet, artificial intelligence, robots and other elements of the information and communication technology revolution. Now, rather than showing signs of ending, this revolution continues to gain momentum. In ten years, life style, business, economic and social activities and structures will be nothing like they are today. This will create an age full of big dreams.

We are in the midst of one of the most dramatic periods of change in the history of mankind. One other such period was the age of exploration in the 15th century when Europeans discovered a new continent and crossed the sea with dreams and hopes. Another was when the gold rush triggered a massive migration of people to the American West in the 19th century. Japan’s Meiji and Taisho eras are another example. The country’s modernization advanced rapidly as Japan enthusiastically embraced Western culture. The current magnitude of change is comparable to or perhaps even greater than these historic periods of upheaval.

A combination of success stories and decline

Enormous changes generate many business opportunities. Everyone is familiar with the term “American dream.” But success stories happen in other places too, including China and other countries in Asia. However, business sectors that were the primary sources of success stories in the past are declining. The internet is about to destroy conventional retail infrastructures, banking systems and media businesses, including publishing, television, newspapers and other activities. Most significantly, the advent of blockchain technology may bring an end to the banking deposit and loan business model just as other technologies eliminated the photographic film industry and the phonograph record industry.

The decline of deposit-loan banking and emergence of shareholder capitalism

There is no need to worry. Shareholder capitalism is about to make a dramatic appearance as the new standard-bearer of the financial sector. Through dividends and stock repurchases, stock markets have become the largest channel for returning the surplus earnings of companies to the real economy. In addition, M&A facilitate creative destruction. Also, new technologies make arbitrage possible in a broad range of applications. The resulting drop in interest rate margins to almost nothing has produced a big gap between the prices of equities and other categories of financial assets.

In Japan, government bonds and bank deposits yield nothing while the dividend yield of stocks is 2% and the earning yield is 7%. A similar absolute attractiveness (comparatively higher return) for stocks exists worldwide. Consequently, stocks are the last remaining virgin territory for arbitrage investments on a massive scale. Technology makes it possible to quantify risk and earn increasingly smaller profits involving finance in the narrow sense (debt and financial products with principal guarantees). On the other hand, the uncertainty of stocks cannot be measured. As a result, we are advancing to an age in which stocks will be the source of most financial earnings. This is why the new industrial revolution will probably shift the nucleus of the financial sector from banks to securities companies.

The unlimited upside potential of Japanese stocks

Looking back at the stock price in modern Japan, the Nikkei Average increased by a multiple of about 400 between 1950 and 1990. When the age of the current emperor started in 1989, the Nikkei Average was about ¥30,000. If we assume that the Nikkei Average will be ¥23,000 on June 14, 2019, the same as it is now, then this average will be down about 23% between 1989 and 2019, when the emperor plans to abdicate. If stock prices rise at an annual rate of 10% once the age of the next emperor begins, the Nikkei Average will surpass ¥100,000 in 2034, a period of 15years. During the past 40 years, global stock prices have increased at an annual rate of approximately 10%. This growth rate would propel the Nikkei Average to ¥100,000. At that level, market capitalization would be about ¥3,000 trillion (¥25 million per capita), a spectacular increase over the current ¥686 trillion (¥5.71 million per capita). This may appear to be preposterous. However, the Nikkei Average is up 150% and market capitalization is up 170% during the five and a half years since the end of November 2012, just before the launch of Abenomics.

Japan’s superiority in two areas will fuel a prolonged bull market

Are there valid reasons to believe Japanese stocks can move up at an annual rate of 10%? The answer is yes. During the Heisei Period, Japan has become superior in two areas that will ensure the country has a bright future. First is superiority involving the international division of labor. Japanese companies are no longer number one in their business domains. Instead, these companies now have the technologies and quality that give them “the only one” business domains. As the international division of labor progresses, countries are increasingly dependent on each other. Success requires rare skills. Performing tasks few or no others can do results in higher prices and profits. This produces benefits for a country’s standard of living, economy and investments. Rare skills are precisely what has supported the strong performances of Japanese companies in recent years.

The second superiority Japan gained during the Heisei Period is its geopolitical position. A full-scale struggle for hegemony between the United States and China is about to begin. The direction of this hegemony struggle will obviously depend significantly on whether Japan aligns itself with the United States or China. Japan is more important to the United States than traditional allies like the United Kingdom and Israel. A robust Japanese economy that can go up against China is directly linked to U.S. interests.

Looking back, the geopolitical environment has played a decisive role in determining the health of Japan’s economy. More specifically, the decisive factor has been Japan’s relationship with the United States. Japan has never been in a more advantageous geopolitical position than it is today. Japan bashing accompanied by a stronger yen and trade friction is inconceivable in the current environment. Furthermore, this advantageous position is likely to reinforce Japan’s superiority within the international division of labor.

These two points are the basis for the possibility of a steady 10% annual increase in the Nikkei Average. There can be little doubt that we are about to enter an era where the intelligence to succeed at stock investing will be critical the ability to enjoy the later years of life. The time when people shunned stocks as speculative investments and unearned income has come to an end.

(2) The possibility of a financial market paradigm shift and stock price revolution – From My book “The Study of New Imperialism” published in 2007

The financial market paradigm shift

All the capital of countries around the world is flowing into a single and vast ocean called the international financial market. This is the result of deregulation, the internet, financial technologies (using financial engineering for the instant arbitrage of financial instruments) and other developments. Financial institutions are seeing a decline in opportunities for earning profits. For many years, financial institutions relied on fee income, interest margins and brokerage commissions for their earnings. These activities used the exclusive superiority of these institutions concerning market access charges and fees for the provision of locations and market making. But deregulation and new technologies have largely eliminated this superiority. Income from stock commissions, banking interest margins, gain on trading listed bonds and other conventional activities is falling to almost nothing. This is an historic phenomenon on a global scale. Financial markets have become more efficient and volatility is lower. In addition, both credit risk premiums and the spread between long and short-term interest rates are becoming smaller. Earning a profit is difficult even when using financial engineering.

Higher market efficiency is one benefit of the rapid improvement in the automatic stabilization function. In 2005 and 2006, stock price, interest rate and commodity price volatility was high in financial markets worldwide. However, the fears of market participants were unfounded because this volatility did not trigger inflation or deflationary recession. The reason was the proper functioning of the automatic stabilizer.By facilitating changes in asset prices and interest rates, financial markets perform a stabilization function that keeps economies steady and maximizes growth irrespective of the policies of central banks. In 2006, stock prices plunged in response to sharp upturns in the prices of crude oil and gold and in long-term interest rates. At that time, there were concerns in the United States about inflation, accelerating economic growth and excessive monetary easing by the Fed, which was then led by Ben Bernanke. But more expensive crude oil and higher long-term interest rates themselves prevented the economy from overheating. As US economic growth slowed, there were declines in both crude oil prices and long-term interest rates that created a platform for the next phase of demand expansion. Consequently, it is no longer possible to predict the direction of financial markets and economies by simply watching the actions of central banks.

This environment makes it very difficult to earn a profit in the traditional debt business of loans, bonds and principal guarantees. At the same time, there is a steady increase in returns on equity from both investments and changes in the value of principal. As a result, using debt to procure funds for equity investments is becoming much more appealing.

Frank Knight promoted the uncertainty theory for about 50 years as a neoclassical economist and a founder of the Chicago school of economics. Now, this theory has come back to life. Dr. Knight distinguished uncertainty from risk. He defined risk as an uncertainty that can be measured. Risks can be known by performing calculations that incorporate actual experiences and using statistics for events in the past. The definition of uncertainty in a narrow sense is a risk that cannot be measured or quantified. This is why Dr. Knight concluded that uncertainty is the source of earnings. Furthermore, risk and uncertainty create differences in competition. Complete competition assumes that people have all applicable knowledge. If this is true, then all risks can be measured in the future and that can be no earnings.

But this view changes if we believe that future uncertainty is produced by uncertainties that cannot be measured. In this case, there would be incomplete competition because of the incomplete knowledge in some areas. This type of competition can produce earnings. In the real world, incomplete knowledge and superficial understandings are what determine how people behave and, therefore, economic valuations as well. If there were no uncertainties and everything could be calculated, economic activity would be nothing more than a mundane routine. That means the economic activity of markets would not be dynamic without uncertainty. Moreover, uncertainty is the source of earnings.

From this standpoint, we can say that financial engineering, deregulation and the internet have converted many narrow-sense uncertainties into risks that can be measured. The volume of uncertainty, which is the origin of earnings, has dropped significantly as a result. This is probably exerting downward pressure on financial income. Based on Dr. Knight’s definitions, we should not believe that growth in risk-taking by investors is responsible for the large declines in volatility and credit risk premiums in the world’s financial markets. Instead, these declines should be viewed as the result of the conversion of financial sector narrow-sense uncertainty into risk. Uncertainty involving debt (loans, bonds, principal guarantees) has declined most of all. This explains why profit margins and risk premiums have decreased at financial institutions.

The traditional debt business involves spreads between long and short-term interest rates over specific periods, credit risk spreads, volatility, and other items. But the decline in uncertainty will soon prevent financial institutions from earning any profits from these activities. This is similar to a gold vein 1,000 meters below the surface that is known to public by using advanced underground imaging. With this prior knowledge, extracting the gold would yield no earnings because the cost of the mining rights would factor in the price of gold to be extracted. In other words, the lack of uncertainty would make this business venture unappealing.

Uncertainty is also behind the remarkable growth of hedge funds accompanied by a downturn in the profitability of these funds. Financial profit margins are falling as uncertainty continue to be transformed into risk. In the 1990s when hedge funds first appeared, they used uncertainty to earn profits. Most funds used a global macro approach that aimed for returns based on scenarios. Now, only about 10% of hedge funds use a global macro approach that relies on uncertainty for profits. Most hedge funds use financial engineering to bet on risks or perform arbitrage. No one should be surprised that these funds are no longer generating profits.

The possibility of a stock price revolution

Dr. Knight’s uncertainty has not disappeared from the financial landscape. In the equity sector, there is an enormous volume of information and knowledge that cannot be known inherently or measured statistically. In fact, uncertainty is increasing about paradigm changes in the global economy that cannot be determined with statistics. Investment opportunities have changed, not disappeared. Many opportunities for profits still exist for stocks and other equity instruments and the number of these opportunities is increasing.

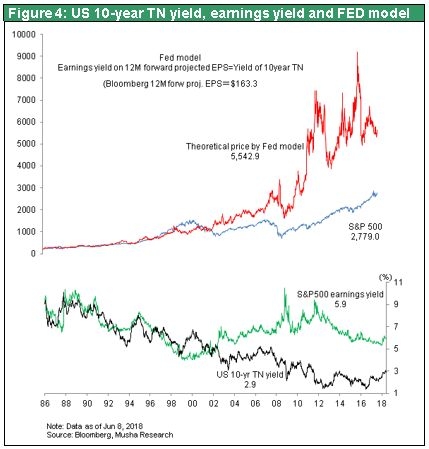

If the so-called Greenspan conundrum becomes the economic norm, there will be a big increase in the theoretical prices of stocks. The dividend discount model divides future income and dividends by a discount rate to determine the present value. If rapid growth raises income and dividends while interest rates remain low or decline, both the numerator and denominator of the present value equation will push stock prices upward. Naturally, actual stock prices will not increase as much as their theoretical values do. The risk premium of stocks has increased significantly. Here, this premium is defined as the difference between a stock’s earning yield (profit divided by stock price) and the long-term interest rate. For the past 20 to 30 years, the forward earning yield of US stocks has been about the same as the long-term interest rate. The result was no risk premium. But recently stock prices have not kept up with earnings growth. In addition, stock prices have not factored in falling interest rates. Currently, US stock prices are about 30% below the theoretical prices. As people become more confident that the Greenspan conundrum will continue, we can expect to see an upward correction of stocks that will eliminate the current underpricing.

A revolutionary shift in stock valuations may be particularly large in Japan. An asset bubble emerged in Japan in the 1980s and burst in the 1990s. History has shown that asset bubbles are frequently a sign of upcoming prosperity rather than the start of a period of decline. Surplus capital and a high level of confidence about the economy are the primary causes of asset bubbles. But these are also two requirements for a healthy economy, as long as excess capital and confidence do not become excessive.

We can say with absolute confidence that Japanese stocks are undervalued. As Figure 5 shows, the gap between stock and bond yields and bank deposit interest rates has become very large. Stocks have an earning yield of 5% and a dividend yield of 1.1%. But returns are 1.6% on Japanese government bonds and 0.3% on bank deposits. A return gap of this size has not existed in Japan for the past 40 years. There is no gap of this size in any other country either. Stocks and bonds are not the only places with significant gaps. Return gaps have grown to unprecedented levels across the entire spectrum of investments: 0.3% for bank deposits, 1.6% for long-term bonds, 3% to 5% for real estate, a stock earning yield of 5% to 6%, a return on past business investments (operating margin on invested capital) of 6% to 7%, and an expected return of more than 10% (Musha Research estimate) on upcoming business investments. These numbers demonstrate that owners (landowners, homeowners, shareholders, business owners) can earn extremely high surplus returns (the risk premium).

Investors have become extremely cowardly about the risk associated with becoming an owner (defined as holding 100% of an asset; an equity holder owns only part of an asset). There are three reasons. First is uncertainty about the sustainability of corporate earnings. Second is worries about a sudden upturn in long-term interest rates caused by the end of deflation and start of inflation. Third is other sources of concern. For example, people may fear that an event that worsens supply-demand dynamics. Such dynamics include sales of stocks by pension funds, the sale of treasury stock or the issuance of new shares to procure funds. Or people may be worried about an event detrimental to shareholder value, caused by a merger, decrease in retained earnings and issuance of convertible bonds with a downward revision provision or other actions. However, not one of these three reasons is a factor that is either decisive or that could last for a long time.

As was just explained, an unusually high risk premium signifies that risk-takers will receive substantial rewards. During the past few years, activity has been high in the vulture fund, M&A, real estate and REIT, private equity and other investment sectors. All these investments are apparently finally starting to raise prices of real estate and stocks. The flow of capital from these sources is beginning to shift from marginal categories to the core of various markets. Individuals are putting money into mutual funds and financial institutions are moving money to assets with higher risk and higher potential returns. These institutions are taking money from loans and government bonds in order to increase exposure to hybrid financial instruments, financial derivatives and other investments. Individuals in Japan have financial assets of about ¥1,500 trillion, mainly in assets with principal guarantees and fixed returns (ultra-low interest rates). Signs are emerging that people are starting a “great escape” from these low-return asset categories.

An enormous correction in the valuations of Japanese stocks has occurred every 10 to 15 years. As you can see in Figure 6, the metrics for assessing stock prices have changed several times. Briefly prior to World War II and during the postwar period of turmoil, stock valuations were so low that dividend yields were far higher than corporate bond yields. Dividend yields were also high in the United States between the end of the Great Depression and the 1950s. Stock prices reflected the risk of a big dividend cut in the next year. From the end of World War II until 1957 in Japan and from 1955 to 1965 in the United States, dividend yields were generally the same as corporate bond yields. Dividends alone determined stock valuations. Investors completely ignored growth in the value of a stock resulting from the increase in shareholders’ equity as earnings were retained year after year.

Since the late 1950s, stock prices have not dropped even though companies reduced dividends when the economy weakened. The earning yield of stocks and the yield on corporate bonds were closely linked. Stock prices were underpinned by the sale of stock at face value (equivalent to a dividend increase) as companies grew and by inflows of money from mutual funds. This link existed through the 1960s and ended in 1971. Stock prices in Japan climbed even higher between 1972 and 1985. Higher prices cut the earning yield of stocks to about half the corporate bond yield. The PER of stocks in Japan increased from about 10 in 1971 to more than 20 during this period. There was consistently strong demand for stocks among foreign investors and demand associated with the growth of corporate cross shareholdings. Due to this demand, there was a large number of stock offerings at the market price.

Between 1985 and 1990, stock prices in Japan surged as the country’s asset bubble grew. The yield on corporate bonds was three times higher than the earning yield of stocks. Furthermore, the PER rose to around 50. Massive monetary easing to help defend the dollar, growth in surplus liquidity, more corporate cross shareholdings and other factors that fueled the demand for stocks were responsible for this remarkably high valuation.

Stocks subsequently plunged between 1990 and 2001 in response to monetary tightening, the end of the asset bubble, and big downturns in the Japanese economy and corporate earnings. Since stock prices fell along with earnings, the earning yield of stocks remained level at approximately 2%, which equates to a PER of 50. But the corporate bond yield was also down significantly. From 2001 to 2003, these events returned Japan to the 1960s valuation when the earning yield of stocks and corporate bond yield were the same. In 2004, the dividend yield was near the corporate bond yield, taking Japan back to the ultra-low valuations that existed in the 1950s immediately after the end of World War II.

These different periods of stock valuations over the years demonstrate that stock prices are more than simply a reflection of a company’s fundamental value (earnings, interest rates). Prices are also linked to big shifts in valuations (popularity). Looking at periods of three to five years, changes in valuation have had a much greater impact on stock prices than the underlying financial value did. Particularly noteworthy is the big impact that the availability of credit and stock trading liquidity have on how a stock is valued.

A variety of fundamental causes are responsible for the extended stagnation of the Japanese economy. But the direct cause was an extreme credit crunch and drop in lending by banks. The credit crunch triggered a sharp drop in stock valuations. As Japan became deeply mired in asset deflation, stock valuations fell even more. With credit now readily available, the public’s aversion to risk is declining and the risk premium is becoming smaller. These changes in the investment climate are likely to produce a significant increase in stock prices.