Feb 12, 2014

Strategy Bulletin Vol.114

The Puzzling Nikkei Editorial Supporting Limits on GPIF Holdings of Risk Assets

Nikkei’s opinion is difficult to justify

On February 11, there was a Nikkei Shimbun editorial titled “No reason for expectations regarding excessive investments in risk assets by pension funds.” The Advisory Council of the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) asked the fund “to allocate a smaller portion of assets to Japanese bonds and a larger share of assets to stocks and overseas bonds.” But the Nikkei believes that this fund should use more realistic and reliable investment policies. This position reflects the U.S. social security system that invests all its funds in treasury securities. There is a belief that any losses from stock investments using social security funds would create a loss of confidence in this system. Investments and asset management require the pursuit of a completely rational approach. The Nikkei’s stance does not have any rational basis and furthermore rejects the asset management recommendation of the experts with no basis at all. By adopting this position, the Nikkei is maligning its own value. The editorial appears to be attempting to influence public opinion by having the Nikkei act as the mouthpiece of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the GPIF.

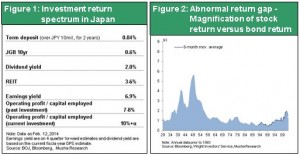

Japanese government bonds may have the highest risk of all

Stating that Japanese government bonds are risk-free is possible only when there is deflation. Once inflation starts, the value of pension assets is certain to decline. Moreover, pension payments will increase with inflation. When this happens, there is no doubt that holding Japanese government bonds that currently yield only 0.6% will not produce sufficient funds for these payments even when using funds from redemptions. This is why the Advisory Council stated that there is a significant danger that investments in Japanese government bonds may be the riskiest investments of all. Currently, most market observers agree that a global “great rotation” is taking place as investors shift funds from bonds to stocks. As this shift occurs, remarkable growth is taking place in the imbalance between the valuations of Japanese stocks and bonds. As I explain in another bulletin, I believe it is very likely that Japan has the most overvalued bonds and most undervalued stocks in the world.

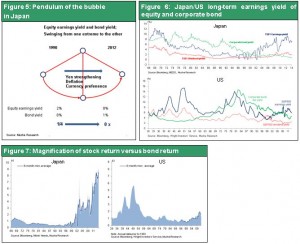

The difference between the US and Japan

At one time, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan said that the US Social Security system should not invest in the stock market. However, the Fed model of “stock yields equal treasury yields” was firmly in place. In this environment, investments in treasury securities produced the same return (benefits from the use of capital) as capital created in the private sector did. But this is not the case in Japan today. The return on private-sector investments is 7% to 2% (7% income yield and 2% dividend yield) and 6% to 3% for J-REIT dividends. But the yield on Japanese government bonds is only 0.6%. Asset prices in Japan are abnormal. There is a huge risk premium due to the extremely low return on safe assets and the high return on assets with risk. As a result, Japanese financial markets have completely stopped functioning as a place that supplies risk capital. Massive financial assets held the people of Japan that total JPY1,600 trillion are hardly being used at all.

Figure 1: Investment return spectrum in Japan

Figure 2: Abnormal return gap – Magnification of stock return versus bond return

The GPIF must not be neutral or agnostic

According to Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, the objective of quantitative easing is to enable financial markets to once again function as a source of risk assets. After all, it would be impossible to end deflation without restoring this function. As Mr. Ito, chairman of the Advisory Council, noted, as a government institution, the GPIF has an obligation to increase holdings of risk assets to a suitable level in order to seek higher returns. GPIF should take actions on its own to create a virtuous cycle that ends deflation so that the fund can receive the subsequent benefits. Consequently, as an investor as well as a government institution, the GPIF must not adopt a neutral or agnostic position. As an institution that manages assets, GPIF must bet on one of the two options ? deflation will continue or deflation will be conquered. As a public fund, GPIF must decide to be either “anti-Abenomics” or “pro-Abenomics.” The GPIF absolutely cannot shirk this responsibility by adopting the attitude of a passive observer.

The Wall Street Journal has the opposite viewpoint

There was an article in the February 10 Wall Street Journal titled “Japanese Stocks Swing to a Foreign Beat.” The article noted:

Japan has a stable government, a deep pool of institutional investors, free flow of capital and transparency. This is a formula for a liquid market that plunges only on remarkable occasions. Yet the Japanese market’s 30-day volatility, as measured by Thomson Reuters, is on par with emerging-market hotbeds Argentina and Thailand. So what is behind all this to-ing and fro-ing? Blame a messy mix of feedback loops. Japanese are a minority in their own market now, with overseas money accounting for nearly 60% of trades on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in January. A decade ago it was 35%. The catch is that for foreigners to take advantage of rising Japanese stocks, they have to short, or bet against, the yen. This is to prevent currency moves from erasing gains. Tweak the yen, and stocks follow. Last week, fears that the U.S. recovery was losing steam sent U.S. bond yields lower. That reduced the difference, or spread, between Japanese and U.S. bonds. A narrower spread means that there is less incentive to hold dollars, so the yen rises. Computer-programmed trading systems sense the yen rising and sell Japanese stocks, while also unwinding short yen trades. The cycle continues.

The Wall Street Journal article went on to say:

the increasing popularity of exchange-traded funds?especially among foreign investors desiring a quick, cost-effective way to dip into and out of foreign markets?likely exacerbates volatility. The Bank of Japan and its monetary-easing program hangs over all this. More easing later this year, which many expect, should mean a weaker yen. That draws in more foreign investors, who made a ton betting on monetary easing in the U.S. and recognize a similar liquidity-driven opportunity. Similar to the U.S. in recent years, investors are tending to move together in a risk-on, risk-off fashion. When will all this end? Getting Japanese pension, insurance and individual investors back into stocks would smooth the rough edges. They don’t have yen trades to unwind. Seeing Japanese take more risks with their savings also would be proof that “Abenomics” really is working.

“Until then”, according to the article, “volatility rules”.

One way to view the extreme aversion to risk among Japanese investors is that this aversion itself is creating higher risks by raising the volatility of Japanese stocks. The strong yen, deflation and abnormal drop in asset prices all caused Japanese investors to lose confidence. In many respects, this situation can be regarded as “the self-destruction of Japanese investors who have become extremely averse to risk.”

Figure 3: Asset allocation by institutional investors – World and Japan

Figure 4: Asset allocation in Japan and US

The following is an excerpt from Strategy Bulletin vol. 108 dated on Nov. 18, 2013.

This undervaluation has never been seen before anywhere in the world. Eliminating this negative bubble would push prices even higher. The income return on Japanese stocks is currently 7%. That means there is \7 of income for every \100 of stock (of which \1.5 represents dividends). By comparison, the return on \100 invested in a bond is 0.8%, or \0.8. The difference is about 8 times. Of course, the return on bank savings accounts is zero. Despite this gap, money did not flow into Japan’s stock markets. We are now witnessing the beginning of an enormous wave that will end this undervaluation.

Figure 5: Pendulum of the bubble

Figure 6: Japan/US long-term trends of earnings yield of equity and corporate bondin Japan

Figure 7: Magnification of stock return versus bond return