The mountain of late excuses for selling

Due to the volatility in stocks, bonds and the yen, some people are criticizing Abenomics as if they have already decided it has failed. The biggest target of this criticism is the “first arrow.” The bold monetary easing at different levels by the Kuroda-led Bank of Japan is viewed as “alchemy.” Criticism reflects the judgmental stance that ultimately nothing can be changed by using the power of money alone. However, I believe that this stance itself is an over-evaluation of money.

The same is true of financial markets: Excessive pessimism is pointless. I think that a positive stance should be retained over the medium- and long-terms. The volatility of Japanese stocks since May 23 (especially the big drops) is nothing more than a technical correction. Investors in Japan and overseas were looking for the right time to lock in profits after Japanese stocks rose 80% in only six months. They used something for an excuse to sell some holdings. This is the proper view. Hedge funds and other overseas short-term investors were major buyers. These investors had probably built-up positions short on the yen and long on Japanese stocks. Selling to close out both of these positions most likely took place on a large scale prior to the end of the quarter ending in June. Just as in 2012 when the adjustment of these positions is completed in the second half of June, onwards, will be an excellent time to take on risk again.

Figure 1: Major equity indices (2009/3/1=100)

Figure 2: Exchange rates of major currencies against Japanese Yen (2007/1/31=100)

Reasons to sell are full of contradictions – Shrinking QE is good rather than bad news

Although stock prices are volatile because of position adjustments, two economic fundamentals are being used as excuses for selling. The first is disappointment in the Chinese economy. The other is the view that Fed’s exit from quantitative easing is in sight. Disappointment in the Chinese economy is nothing new because this subject has been discussed for many years. There is reason for concern from a medium to long-term perspective. But if the Chinese economy does in fact weaken, this should instead be regarded as an indication that the global movement toward monetary easing will become a

long-term trend.

The view regarding U.S. quantitative easing is a stance with an ulterior motive. Many people in Japan viewed the Congressional testimony of Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke in late May as a signal that quantitative easing will be downsized. But the opinion of the monetary policy experts that I know in other countries is different. They believe that Mr. Bernanke’s statements about an exit show no change at all. He has adopted a neutral stance of making a decision while monitoring employment statistics. Even if the Fed starts to draw down quantitative easing, this would not be entirely bad news. Ending quantitative easing would mean that the Fed is confident that unemployment is falling and the real economy has returned to a self-sustained recovery. Therefore, if the Fed makes this shift, it would be difficult to imagine a prolonged downturn of U.S. and Japanese stocks because a transition would be taking place from monetary policies to corporate earnings as the driving force behind stock prices.

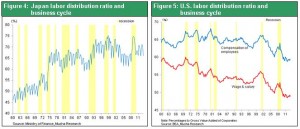

On the other hand, a continuation of quantitative easing would signify that unemployment has not declined enough and there is no outlook for a self-sustained recovery. There is only one thing to worry about: the possibility that quantitative easing cannot continue despite the lack of rebounds in jobs and the economy. But there is almost no possibility of this happening. Three potential major obstacles to quantitative easing exist: (1) a decline of faith in the dollar; (2) an acceleration in inflation; and (3) a rapid drop in confidence in government finances. However, improvements are occurring in all three areas. That means selling stocks because of the expected end of the current U.S. monetary policy is nothing more than a late excuse. In fact, there has been no significant reaction of U.S. stocks to the possible end of quantitative easing. Long-term interest rates are higher in Japan and the U.S. But rates have simply rebounded from the extremely low levels of the past six months. Interest rates have not reached a point that creates panic about a sharp increase.

This reminds me of 1994 when there was panic in some market sectors about a sharp upturn in long-term interest rates as Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan started to raise interest rates. But long-term interest rates that surged from the 5% level to almost 8% returned to the original level about 12 months later. Furthermore, there was no interruption in economic growth. As a result, we can now say that these events were the result of confusion caused by defective communications between markets and the Fed. I believe that the Fed is prepared to disseminate information as needed in order to prevent repeating this mistake.

Figure 3: U.S. LT & ST interest rates and S&P500

Do not underestimate the power of Kuroda’s bazooka – “Don’t fight the BOJ”

Japan’s genuine quantitative easing program is about to enter the full-scale phase. The BOJ is starting a money-supply process on an unprecedented scale that will double its balance sheet from the end of 2012 to the end of 2014. No one knows how market prices will react. Furthermore, no investor has an outlook for the proper levels of financial markets as this massive quantitative easing takes place. Consequently, the recent market volatility can be viewed as a natural process of looking for a consensus on where prices should be. Volatility should not at all be viewed as the start of a long-term drop in stock prices as investors shun risk or as an indication that Abenomics is failing. The Wall Street ironclad rule “Don’t fight the Fed” is applicable in Japan, too. The support of the central bank, which has complete control over inconvertible paper money, is vital for the health of the real economy as well as the success of investments. Looking back, I was mistaken to expect higher stock prices when the Bank of Japan was led by Masaaki Shirakawa, who had no interest in stocks and foreign exchange rates. My advice to pessimists is to not make the same mistake now that the Bank of Japan is led by Haruhiko Kuroda.

Abenomics is obviously having a favorable effect on corporate earnings, chiefly in industries with substantial exports. Earnings of all listed companies in Japan will probably set a new record in the current fiscal year. Companies are very likely to utilize their large amounts of capital in a variety of ways. As a result, although the benefits of the third arrow (growth strategy) of Abenomics are debatable, we can expect to see the full-scale emergence of chain-reaction benefits from the first arrow.

Money is a catalyst – Criticism of easing is the flip side of the over-evaluation of money

Today, the biggest issue for developed economies is the inability to eliminate surplus labor and surplus capital even as manufacturing, information technology and certain other sectors post remarkable increases in productivity. This is particularly true regarding Japan, which has struggled with the service price deflation. To express this another way, overcoming this problem would probably create significant growth potential. For developed countries, the key to solving this issue is low-productivity domestic-demand rather than high-productivity global demand. Even growth in high-productivity global demand (for example, there are limits to the desire of Apple and Google for more workers and investments regardless of how much they earn) cannot absorb surplus labor and capital within a particular country. Surplus capital can be returned to a nation’s economy to some degree by using the asset effect resulting from stock buybacks and other actions. However, the size of this benefit is limited.

Wealth must be redistributed from high-tech and other high-productivity sectors to services and other low-productivity sectors linked to domestic demand. The goal is the widespread allocation of purchasing power among the people of a country. To accomplish this, the most effective method is growth in disposable income. That means an increase in nominal income, which requires inflation. Prices in the high-tech sector and manufacturing sectors need to fall while prices of services, where there is much latent demand, need to climb in order to achieve a transfer of income.

Import deflation caused by the yen’s strength enabled the people of Japan to maintain their living standards even though nominal income did not increase. Companies did not return surplus wealth in the form of higher wages, but workers allowed this to happen. However, expectations for inflation may increase because of the weaker yen and economic recovery (and associated tight labor market). In this case, companies would probably be forced to allow wages to rise even without any prompting from the government. Why? In the United States, wages are determined by the supply and demand of workers. In Japan, though, wages are closely linked to prices because covering the cost of living is a major aspect of salaries.

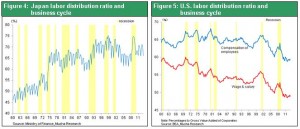

Incidentally, in the United States, labor’s share of income is highest at the peak of an economic upturn because this is when demand for workers is also highest. But in Japan, wages are inflexible in relation to changes in the economy and demand for workers. Consequently, labor’s share of income in Japan is lowest at the peak of an economic upturn.

Figure 4: Japan labor distribution ratio and business cycle

Figure 5: U.S. labor distribution ratio and business cycle

On the surface, criticizing quantitative easing as a form of alchemy appears to be the most on-target criticism of all. My view is that the current quantitative easing is a catalyst for stimulating the creation of new demand (by utilizing idle capital and idle labor). Another way to regard the criticism that the power of money alone can’t change anything is that these people are asking too much of money. Money can never create new value regardless of how it is used. However, money is the most powerful catalyst for triggering the following chemical reaction for producing wealth:

SL (surplus labor) + SC (surplus capital) → D (Creation of new demand)

Viewing quantitative easing as alchemy is a misperception originating from the twisted belief that the catalyst, which fills only a supporting role, is instead playing the central role. No matter how you look at it, the problem is always the existence of idle labor and idle capital. Money must be used exclusively as a catalyst for combining these two components for the creation of new demand. Fed Chairman Bernanke and BOJ Governor Kuroda are well aware of this point. This is probably why they have continued to implement quantitative easing on this scale. In simple terms, that means quantitative easing measures should be continued until the desired result is obtained (until the real economy has clearly returned to a course of self-sustained growth).

Physical growth of emerging countries is near the limit – Domestic demand in developed countries will be the next source of growth

My final subject uses an even larger perspective. I believe that the driver of global economic growth is about to shift from growth fueled by the amount of physical goods in emerging countries to growth backed by the quality of life in developed countries. Physical growth in emerging countries is likely to reach its limit very soon. In particular, the difficulty of sustaining growth has become quite clear in China, the core member of the BRIC countries. A large amount of investments in three sectors are expected to become virtually worthless: real estate investments, corporate capital expenditures and public-works expenditures. The reason is that the needs of the Communist Party rather than economic rationality were used to select many of these investments. Companies and governments alone have accumulated wealth. Labor’s share of income has dropped to an unusually low level and buying power of the people of China has increased only in large cities. Apparently, the Chinese economy has finally entered a structural dead end. Rapid economic growth in Russia and Brazil (as well as Australia, which is not a BRIC country) as well has been supported in large part by China’s ravenous economy. Falling prices of resources that will probably accompanying slowing economic growth will most likely result in unavoidable erosion in the economic clout of the BRIC countries.

If the BRIC countries do, in fact, reach the limit of their physical economic growth, the only other sources of growth are other emerging countries and, most of all, developed countries. Expectations are highest for the United States. The correction after the Lehman shock is over and full-scale economic expansion has started. Housing prices dropped 30% from the peak but are now rebounding. Another housing investment boom is about to begin. In addition, the United States is benefiting from growing demand for services like education, health care and entertainment. The U.S. economy continues to generate more jobs, too. Quantitative easing overseen by Fed Chairman Bernanke is facilitating the use of surplus workers and capital to create new demand. This process is succeeding at laying the groundwork for long-term prosperity.

Abenomics and the bold monetary easing at different levels by the Kuroda-led Bank of Japan are extensions of the Fed’s actions. If successful, Japan’s initiatives would spark growth in domestic-demand industries, which underpin growth of the quality of life of the people of Japan. This accomplishment would, in turn, produce another driver of global economic growth alongside the United States to replace the BRIC countries.

On the surface, criticizing quantitative easing as a form of alchemy appears to be the most on-target criticism of all. My view is that the current quantitative easing is a catalyst for stimulating the creation of new demand (by utilizing idle capital and idle labor). Another way to regard the criticism that the power of money alone can’t change anything is that these people are asking too much of money. Money can never create new value regardless of how it is used. However, money is the most powerful catalyst for triggering the following chemical reaction for producing wealth:

On the surface, criticizing quantitative easing as a form of alchemy appears to be the most on-target criticism of all. My view is that the current quantitative easing is a catalyst for stimulating the creation of new demand (by utilizing idle capital and idle labor). Another way to regard the criticism that the power of money alone can’t change anything is that these people are asking too much of money. Money can never create new value regardless of how it is used. However, money is the most powerful catalyst for triggering the following chemical reaction for producing wealth: