Aug 08, 2013

Key Strategy Issues Vol.K295

The Chinese economy at a turning point

- The liquidation of abnormal investments is approaching

China’s prosperity is about to reach its peak. The country is likely to enter an extremely difficult period with respect to its economy and politics. In 2012, the World Bank and China’s National Development and Reform Commission jointly prepared an outlook for the Chinese economy. Although the outlook calls for China to surpass the United States in 2030, this is very unlikely to happen. Instead, I think that a rapid slowdown in China’s growth and extreme difficulty in preserving the Communist Party dictatorship are inevitable. Currently, the growth of the Chinese economy is slowing rapidly. Three restrictions on growth are appearing: (1) excessive investments, (2) a sharp erosion in the country’s competitive edge; and (3) the geopolitical barrier. Furthermore, understanding China’s problems requires adopting a historical perspective. For example, we need to examine the current stage of the country’s history and how the economy developed under the guidance of the Communist Party.

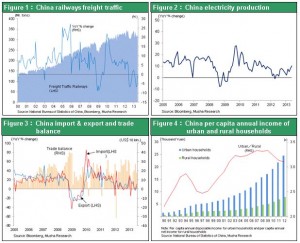

Chapter 1 China stands on the verge of a major transition

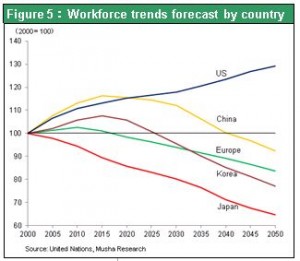

After China joined the World Trade Organization in December 2001, the country staged economic growth on an unprecedented scale for the next decade. In only a short time, China became the world’s factory. Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, China was the world’s engine for economic growth amid a global deflationary crisis. By making internal investments of 4 trillion yuan, China made an enormous contribution to the global economy. But today, China’s economic growth is slowing rapidly. In 2012 and the first two quarters of 2013, China’s GDP has grown at an annualized rate of less than 8%. This is the lowest level since 2000, except immediately after the Lehman shock. Slowing growth has brought the movement of goods to a virtual halt. Railway freight volume and electricity consumption have both peaked during the past six months. The trade value (Export &Import), which had been posting annual growth of 20% to 30%, has dropped to about the same level as one year ago. All indicators point to a sharp decline in the pace of economic growth in China. Significant problems are emerging with regard to the fundamentals of China’s economy, too. One is the slow pace of reforms. The Hu-Wen administration wanted to eliminate income differences, particularly between urban and rural regions, to create a socialist harmonious society. But there has been almost no progress. Reforms of SOE (State Owned Enterprises) companies and support for privatecompanies have been failures. As before, there is no end in sight to corruption and decay in political leadership and the government. The most serious of all these problems is the mismatch in the allocation of labor. China’s rural areas still have massive amounts of surplus labor. But in coastal regions, a steep upturn in wages is taking place because of a severe shortage of migrant workers from rural areas. Furthermore, jobs are difficult to find: about 40% of the rapidly increasing ranks of college graduates are unable to get a job. China may appear to be prosperous on the surface. However, resources are not being properly allocated especially in labor force. . Most of all, there is no allocation at all for workers. Measures to resolve this misallocation are still limited to economic programs that are overseen entirely by bureaucrats. As a result, artificial actions are having an increasingly greater influence on China’s economy. It is no surprise that dissatisfaction is growing among the people of China. This sentiment is being shared among many people by using the Internet to bypass controls on information. The result is mounting social instability. Figure 1:China railways freight traffic Figure 2:China electricity production Figure 3:China import & export and trade balance Figure 4:China per capita annual income of urban and rural households  The biggest problem of all is that China’s investment returns are about to encounter an enormous red light. Stock prices are falling and corporate earnings have plummeted. We have also seen a sudden downturn in inflows of capital to China following years of steady growth. Direct investments have become negative and the virtuous cycle that fueled prosperity has started to rotate in the opposite direction. This is why China implemented economic stimulus measures prior to last year’s transition to a new administration. Monetary easing, the end of a freeze on increasing steel output and faster railway investments are just a few of these measures. Despite these actions, China’s economy is already showing symptoms of falling momentum. China is also feeling the effects of a natural restriction on growth: a declining population. According to U.N. forecasts for changes in the working populations of major countries, only the United States is expected to experience growth over the next few decades. Working populations are already declining in Japan and Europe and will start declining in China, too. Figure 5:Workforce trends forecast by country

The biggest problem of all is that China’s investment returns are about to encounter an enormous red light. Stock prices are falling and corporate earnings have plummeted. We have also seen a sudden downturn in inflows of capital to China following years of steady growth. Direct investments have become negative and the virtuous cycle that fueled prosperity has started to rotate in the opposite direction. This is why China implemented economic stimulus measures prior to last year’s transition to a new administration. Monetary easing, the end of a freeze on increasing steel output and faster railway investments are just a few of these measures. Despite these actions, China’s economy is already showing symptoms of falling momentum. China is also feeling the effects of a natural restriction on growth: a declining population. According to U.N. forecasts for changes in the working populations of major countries, only the United States is expected to experience growth over the next few decades. Working populations are already declining in Japan and Europe and will start declining in China, too. Figure 5:Workforce trends forecast by country

Chapter 2 Doubts about an economy fueled by investments

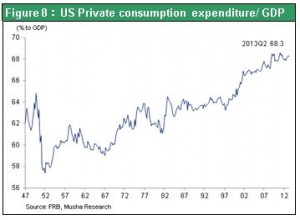

Simply put, China’s economic growth until now has relied on investments. The annual growth rate has dropped quickly from 10.4% in 2010 to 9.2% in 2011 and 7.8% in 2012 and the first quarter of 2013. Annualized growth slowed again to 7.4% in the second quarter. Looking at categories of demand, investments have been the overwhelming source of growth for the past decade. Investments accounted for about 60% of growth and net exports were also a big contributor between 2000 and 2005. But exports have decreased as a driver of economic growth over the past few years, which left only investments to support growth. On the other hand, consumption is raising China’s GDP by only slightly more than 4%. Consequently, a drop in investments would immediately cut economic growth to 4% or maybe even less. There are doubts about China’s ability to sustain investments. This is why I believe that slower growth or a decrease in investments will probably lead to an even larger downturn in growth. A comparison of fixed capital formation as a percentage of nominal GDP shows how extreme China’s investment-dependent economy is. When this percentage in China surpassed 40% seven or eight years ago, people thought investments were way too high. But this figure subsequently rose to 45.7% in 2012. By comparison, this ratio was only 26.7% in South Korea, 21.2% in Japan, 17.6% in Germany and 15.8% in the United States in 2012. Fixed capital formation is accounting for almost half of China’s GDP. Even going back many years, there are almost no instances in any other country of this abnormal situation in which investment demand is consistently higher than consumption. Therefore, we can say that investments made China’s strong economic growth possible. But the problem is determining what this growth really means. Figure 6:Contribution by demand items to China’s economic growth Figure 7: Gross fixed capital formation ratio to nominal GDP in major countries  The common-sense definition of investments is money used for a future benefit. Education is an excellent example. But even though education produces future benefits, these expenditures are classified as consumption for accounting and statistical purposes. As you can see, there is a clear difference between the generally accepted concept of investments and the definition of investments for accounting and statistical reports. For accounting, an investment is the capitalization of an expense. That means putting off an expense. For example, using ¥10 billion will immediately create demand but there will be no expense at all. This is the meaning of an investment. This is why investments require the collection and depreciation of invested capital in the future. But no one knows if a machine, real estate or other investment will actually produce benefits. So investments have a pre-determined cost but an uncertain benefit. Increasing investments can generate strong economic growth. However, a mistaken investment is equivalent to digging your own grave. China’s excessive investments have created this situation. The opposite of China is the U.S. economy, which has unusually strong consumption. Over the past 50 years, consumption has increased steadily from about 60% to 70% of the U.S. GDP. Many pessimists say that this shows the United States is using money for short-term expenditures. But this is a mistake. The United States has transformed itself from an industrial society to a society centered on information. The majority of investments are in knowledge and people, such as for developing software, accumulating intellectual property and education. No country classifies education expenditures as investments for accounting purposes. So the more money a country spends on education, the higher its consumption becomes. Education spending will definitely yield substantial benefits in the future. Nevertheless, this is classified as consumption by accountants and treated as an expense. This explains why U.S. consumption has been climbing. Viewing the accounting and statistical concepts of investments from our common-sense standpoint thus results in a major error. Figure 8:US Private consumption expenditure/ GDP

The common-sense definition of investments is money used for a future benefit. Education is an excellent example. But even though education produces future benefits, these expenditures are classified as consumption for accounting and statistical purposes. As you can see, there is a clear difference between the generally accepted concept of investments and the definition of investments for accounting and statistical reports. For accounting, an investment is the capitalization of an expense. That means putting off an expense. For example, using ¥10 billion will immediately create demand but there will be no expense at all. This is the meaning of an investment. This is why investments require the collection and depreciation of invested capital in the future. But no one knows if a machine, real estate or other investment will actually produce benefits. So investments have a pre-determined cost but an uncertain benefit. Increasing investments can generate strong economic growth. However, a mistaken investment is equivalent to digging your own grave. China’s excessive investments have created this situation. The opposite of China is the U.S. economy, which has unusually strong consumption. Over the past 50 years, consumption has increased steadily from about 60% to 70% of the U.S. GDP. Many pessimists say that this shows the United States is using money for short-term expenditures. But this is a mistake. The United States has transformed itself from an industrial society to a society centered on information. The majority of investments are in knowledge and people, such as for developing software, accumulating intellectual property and education. No country classifies education expenditures as investments for accounting purposes. So the more money a country spends on education, the higher its consumption becomes. Education spending will definitely yield substantial benefits in the future. Nevertheless, this is classified as consumption by accountants and treated as an expense. This explains why U.S. consumption has been climbing. Viewing the accounting and statistical concepts of investments from our common-sense standpoint thus results in a major error. Figure 8:US Private consumption expenditure/ GDP

Chapter 3 Investments that are not rooted in demand

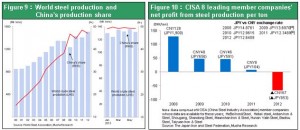

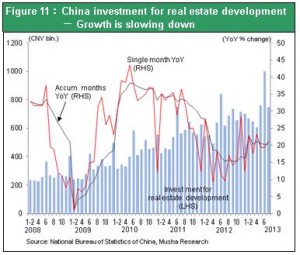

China has channeled its investments mainly to three sectors: (1) massive capital expenditures in heavy and chemical industries like steel, shipbuilding and petrochemicals, primarily government-owned companies; (2) public-works projects such as high-speed rail lines and expressways; and (3) real estate. In all three sectors, China has made unbelievably excessive investments. For more than three decades between the 1970s and 1990s, annual global crude steel output remained basically level in the 800 million to 900 million ton range. But output started rising quickly around 2000. Current annual output is 1,400 million tons, which is an increase of about 50% over the past decade. China is responsible for all of this explosive growth in crude steel production. Ten years ago, China accounted for only 10% of the world’s crude steel output. Today, China supplies about half of the world’s crude steel. Over a very short time, China created an extraordinary steel production infrastructure. The issue is whether there is sufficient demand to absorb this added capacity which is equivalent to half of the global production. Global steel prices are already worsening rapidly due to this situation. In 2013, global crude steel output and China’s share of this production have been absolutely flat. Although output has not started to fall yet, there is little doubt that production will soon start to decline. When crude steel output stops climbing, earnings in China’s steel industry will plunge. Total earnings in China’s steel industry peaked at 160 billion yuan in 2007. In 2012, the China Iron & Steel Association predicted that the industry will incur its first loss. Despite this situation, the Chinese government as part of its economic stimulus measures has lifted the freeze on the construction of two 10 million ton high-end blast furnaces at Wuhan Iron and Steel (Group) Corp. and Baoshan Iron & Steel Co., Ltd. Approving more output even though there is an oversupply of steel clearly shows that China is targeting overseas markets. China has finally reached the point at which its extreme oversupply of steel is about to explode into other countries. Similar problems are already occurring worldwide in the solar panel, shipbuilding and other industries. In the past, China was a source of inflation because of its surplus demand. But now China is about to become a source of deflation because of its surplus output rather than the cheap cost of labor. This is what has resulted from the country’s massive volume of investments. Australia is China’s largest supplier of iron ore. According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, housing construction and the associated use of steel in China are at the peak right now and will soon start to fall. The outlook is the same for China’s automobile sector. China is the world’s largest automobile market with annual sales currently at about 19 million vehicles. But there are doubts about the country’s ability to keep demand in the 18 million to 19 million vehicle range. Annual U.S. automobile sales were 5.4 million vehicles in 1929 at the start of the Great Depression. That means U.S. automobile output capacity was more than 5 million vehicles immediately before the Great Depression. Annual automobile demand in the United States did not surpass the Great Depression peak of 5.4 million vehicles again until 1949, a period of 20 years. Since the U.S. population was 120 million in 1929, 5.4 million vehicles is equivalent to annual sales of more than 15 million vehicles based on the current population. Figure 9:World steel production and China’s production share Figure 10:CISA 8 leading member companies’ net profit from steel production per ton  These figures show that economies do not grow at a steady rate. Growth occurs along with dramatic downturns caused by surplus supply and output and other big ups and downs. This volatility is particularly likely to happen when excessive investments are made because of shifts in a variety of paradigms. In the real estate sector, China has made massive investments in residential development projects in almost all major cities even though there were not enough people to rent these residences. These developments were not conducted to earn a profit. Residences were constructed to generate revenue for local governments and secure rights and interests. This is the primary reason for the gap between supply and demand. Land in China is owned by the government. Developing a housing project therefore requires buying the right to lease land for a certain number of years. Local governments can earn substantial revenues by selling rights to use land in order to make land available for the construction of housing. Proceeds from the sale of land rights is said to account for 70% to 80% of local government revenues. Consequently, housing developments are essential in order to procure funds for local governments. Prospects for the profitability of a development are not the primary concern. Furthermore, local Communist Party officials and other power brokers who play the main role in the development process have an advantage because of their access to insider information. This creates an enormous amount of rights and interests. As a result, housing is automatically constructed to secure tax revenue and rights and the final demand for the housing is basically ignored. This process may be creating a significant housing bubble and causing excessive investments. In the housing sector as well, China is nearing a major barrier to continued growth in investments. Figure 11:China investment for real estate development - Growth is slowing down

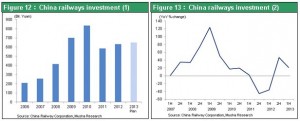

These figures show that economies do not grow at a steady rate. Growth occurs along with dramatic downturns caused by surplus supply and output and other big ups and downs. This volatility is particularly likely to happen when excessive investments are made because of shifts in a variety of paradigms. In the real estate sector, China has made massive investments in residential development projects in almost all major cities even though there were not enough people to rent these residences. These developments were not conducted to earn a profit. Residences were constructed to generate revenue for local governments and secure rights and interests. This is the primary reason for the gap between supply and demand. Land in China is owned by the government. Developing a housing project therefore requires buying the right to lease land for a certain number of years. Local governments can earn substantial revenues by selling rights to use land in order to make land available for the construction of housing. Proceeds from the sale of land rights is said to account for 70% to 80% of local government revenues. Consequently, housing developments are essential in order to procure funds for local governments. Prospects for the profitability of a development are not the primary concern. Furthermore, local Communist Party officials and other power brokers who play the main role in the development process have an advantage because of their access to insider information. This creates an enormous amount of rights and interests. As a result, housing is automatically constructed to secure tax revenue and rights and the final demand for the housing is basically ignored. This process may be creating a significant housing bubble and causing excessive investments. In the housing sector as well, China is nearing a major barrier to continued growth in investments. Figure 11:China investment for real estate development - Growth is slowing down  China already has a high-speed railway network of more than 9,300km even though the decision to start building these high-speed lines was made in 2003. Japan’s high-speed rail lines total 2,400km, so China has built a network that is almost four times larger in less than 10 years. Moreover, China has established the extremely wasteful plan of expanding this network to 16,000km by 2014. Construction of these high-speed lines is mainly the responsibility of the Ministry of Railways, which resembles Japan National Railways, the nationally owned railroad system that used to exist in Japan. Economic considerations are clearly not the basis for these investments. High-speed railway line construction reflects national government policies and the associated investments are creating many rights and interests. Figure 12:China railways investment (1) Figure 13:China railways investment (2)

China already has a high-speed railway network of more than 9,300km even though the decision to start building these high-speed lines was made in 2003. Japan’s high-speed rail lines total 2,400km, so China has built a network that is almost four times larger in less than 10 years. Moreover, China has established the extremely wasteful plan of expanding this network to 16,000km by 2014. Construction of these high-speed lines is mainly the responsibility of the Ministry of Railways, which resembles Japan National Railways, the nationally owned railroad system that used to exist in Japan. Economic considerations are clearly not the basis for these investments. High-speed railway line construction reflects national government policies and the associated investments are creating many rights and interests. Figure 12:China railways investment (1) Figure 13:China railways investment (2)  None of China’s unprecedented investments, whether capital expenditures, public-works projects or real estate, reflects rational economic factors in accordance with a market economy. Investments are end to themselves by implementing Communist Party policies and securing rights and interests and tax revenues. There are significant questions about the ability of these investments to yield benefits in the future. The growth of railway investments, steel industry capital expenditures and other investments is already coming to a halt. However, these investments are almost certain to spread to more sectors of the economy. If these investments started to decline, China’s economic growth would stop.

None of China’s unprecedented investments, whether capital expenditures, public-works projects or real estate, reflects rational economic factors in accordance with a market economy. Investments are end to themselves by implementing Communist Party policies and securing rights and interests and tax revenues. There are significant questions about the ability of these investments to yield benefits in the future. The growth of railway investments, steel industry capital expenditures and other investments is already coming to a halt. However, these investments are almost certain to spread to more sectors of the economy. If these investments started to decline, China’s economic growth would stop.

Chapter 4 Foreign currency reserves underpinned investments

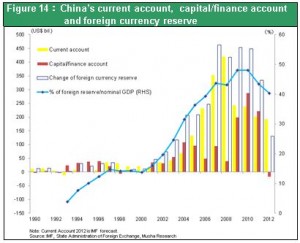

The existence of ample supplies of funds for investments in order to expand China’s economy was the most important motivation. Massive foreign currency reserves are what made this financial environment possible. These reserves increased rapidly as China became more competitive and its exports surged starting around 2000. Moreover, China did not allow individuals to hold foreign currency until about 2007. All foreign currency had to be deposited in banks as a result. Since banks can immediately convert foreign currency into yuan, growth in foreign currency reserves translated into growth of China’s money supply. Consequently, the steep increase in China’s foreign currency reserves contributed to China’s massive money supply. Today, a significant change is occurring with regard to the foreign currency that produced the large amount of funds for investments in China. As a percentage of GDP, China’s foreign currency reserves surged from 0% in the 1990s to 13% in 2000 and 49% in 2010. This was the source of China’s enormous and even reckless investments. In 2012, the reserve-GDP ratio fell to 40% and was about 38% in the first half of 2013. Foreign currency reserves, which backed the issuance of money in China, have peaked and are now declining. (1) China’s huge trade surplus is starting to decrease as rising wages make the country less competitive. (2) Investments by foreigners in Chinese securities and other direct investments are about to stop growing. Until the first half of 2012, Japan alone among the world’s major countries was still increasing direct investments in China. But after the Senkaku Islands dispute started, Japan’s investments have been declining as well. (3) China has eased restrictions on securities investments. However, foreigners are unlikely to buy more Chinese securities because the country has the world’s worst stock market performance and there are worries about slowing economic growth. Even Anthony Bolton of Fidelity Investments, who has been a proponent of Chinese investments, is pulling back from China. In addition, (4) Chinese investors may start to move their money overseas for safety. Despite the serious efforts of Chinese authorities for managing foreign exchange rates, there is an unmistakable downward trend in foreign currency reserves. The decline in these reserves is very likely to make China’s credit crunch even more severe. Foreign currency reserves are not down significantly yet. But there has been a dramatic change in the past two to three years in China’s supply and demand for foreign currency. If these reserves start to fall, China would encounter serious difficulties in issuing currency backed by foreign currency holdings. This is a big problem that China is facing right now and may or may not become catastrophic. Whatever happens, China will no longer be able to sustain economic growth that relies on abnormally high investments for 60% of GDP growth. Moreover, there are doubts about whether or not consumption can replace investments as the primary driver of the Chinese economy. Figure 14:China’s current account, capital/finance account and foreign currency reserve

Chapter 5 Japan succeeded in shifting from investments to consumption

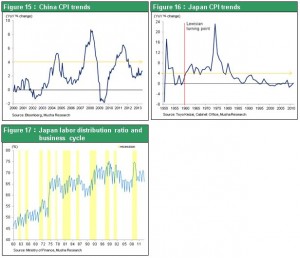

More investments are obviously needed during periods of economic growth. As a country’s economy matures, the main source of growth shifts to consumption. All developed countries have experienced this shift. Can it happen in China, too? Boosting consumer spending requires more spending power, which means higher wages. There are reasons to doubt the ability of the China of today to establish a framework for higher wages and consumption. For Japan, 1960 was a critical turning point (Lewisian Turning Point) in the country’s transition from investment-driven to a consumption-driven economy in order to sustain strong economic growth. Since 1960, inflation in Japan remained steady over the next 20 years at about 4%. That means wages have increased rapidly with productivity growth plus4% inflation. Labor’s share of income rose sharply (from under 50% in the 1960s to about 65% in the 1980s). A strong upturn in wages and the associated inflation generated enormous domestic demand in Japan. Numerous gaps that existed before 1960 were eliminated as a result. For example, the wage differentials between urban and farm workers and between skilled and unskilled laborers narrowed. By about 1975, Japan had become one of the very few countries in the world with an equitable distribution of prosperity. Wage inflation created purchasing power, which in turn greatly raised the living standard of farm workers and unskilled laborers. That means the Lewisian Turning Point is the tipping point at which the market mechanism starts functioning for determining wages. Prior to 1960, Japan had considerable surplus labor in rural areas. This explains why wages did not rise regardless of how much companies increased their earnings in Japan’s robust economy. Market mechanisms were not functioning for the determination of wages. Companies used cheap labor to earn big profits. Earnings were used to make investments that created the foundation for Japan’s economic growth. But this growth did not make the people of Japan more affluent. The year 1960, which was when the U.S.-Japan security treaty was revised, was also a major turning point in Japanese politics. Dissatisfaction regarding the gap between rich and poor was increasing. In 1960, the Ikeda Cabinet announced an income doubling plan based on tolerance and patience. The plan established an environment for consistent wage inflation that produced a momentous shift in the supply and demand for workers in Japan. Up that point, the ratio of job openings to job seekers was less than one. Afterward, there were more job openings than job seekers as surplus farm labor disappeared. Bringing about this transition quickly narrowed the wage gap between farm and urban workers. There was progress with narrowing the skilled and unskilled labor wage differential, too. Rural areas supplied manual workers with no particular skills. But even the wages of these workers rose significantly because of the balance between the supply and demand for labor. China is currently in the similar economic situation as Japan was in 1960. The country stands at a crossroad Now the question is if China can achieve sustainable consumption by switching from investments to consumption and boosting wages. Figure 15:China CPI trends Figure 16:Japan CPI trends Figure 17:Japan labor distribution ratio and business cycle

Chapter 6 Old-fashioned systems are blocking change in China

Consumer prices will show whether or not China can achieve sustainable consumption. If China can sustain inflation of 4%, just as in Japan, wages will climb more than productivity gain. This growth could lead to an increase in domestic demand from consumption. China’s steep upturn in wages until three years ago raised hopes about growth in this demand. Although higher wages raised expenses for Chinese companies, many people thought that China had established an environment for making its citizens more prosperous. However, inflation subsequently declined quickly and is now between about 2% and 3%. In coastal cities, wages are increasing because of the shortage of migrant workers from rural areas. More costly workers are hurting profits. So why can’t China sustain inflation of 4% as Japan did? The cause is the significant mismatch in the allocation of labor that is unique to China. In urban areas, there is a shortage of unskilled workers. But the barrier created by China’s household registration system is preventing unskilled workers from moving from rural areas to cities. The result is rising wages in cities while rural areas still have too many workers. Numerous old-fashioned systems remain in China, notably the household registration system. As a result, there is no improvement in labor’s share of income or in the wage differential between cities and rural areas because of the inability to use labor effectively. This situation has rapidly eroded China’s ability to compete by raising wages in coastal areas, which is causing the trade surplus to decrease. Obviously, these events are forcing companies to shift investments from coastal areas to inland China and other countries. But there are limits on attracting investments in inland areas. Unlike for coastal cities, it is difficult to engage in the processing trade and build export channels to overseas markets. Export-driven economic growth is not easy to achieve in inland China. The only other option is to rely on investments for growth. In addition, the funds for inland investments are derived from economic growth in coastal areas. So these investments would entail shifting the benefits of this growth to inland areas. There is a clear conflict of interest. Making a shift from an economy backed by excessive investments to a consumption-driven economy, as Japan did many years ago, will not be easy. This is the problem in China today, and it is not a problem that will resolve itself somehow over time. GDP shrinks when the growth rate of an investment-fueled economy slows. This makes it impossible for workers to receive a larger share of earnings. From the standpoint of a global oversupply of goods, China is very likely to be forced to resort to dumping to export its products. Doing this would exert more downward pressure on wages. Japan succeeded in transforming from investments to consumption for economic growth. But for China, it is becoming increasing difficult to envision a way to achieve long-term economic growth that is centered on internal demand.

Chapter 7 The Hon Hai business model is no longer valid

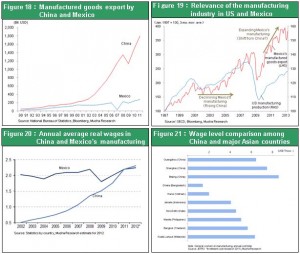

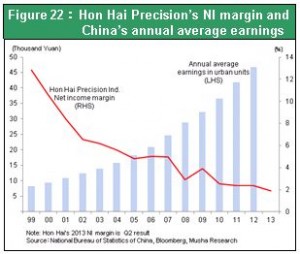

Rising wages in coastal China are making the entire country less competitive. At the same time, China’s decline is being accompanied by increasing economic vitality in the ASEAN countries and Mexico. Since the Chinese economy took off around 2000, growth in production in Mexico has been less than in the United States. But now, manufacturing output in Mexico is increasing much faster than in the United States. Obviously, a shift in manufacturing from China to Mexico has started. Wages have shifted, too. Early in the last decade, wages in China were one-fifth to one-seventh the level in Mexico. But wages in the two countries are almost equivalent. After considering the cost of transportation and other factors, Mexico becomes superior to China as a production base. In addition to Mexico, the ASEAN countries are also benefiting from the outflow of manufacturing from China. Figure 18:Manufactured goods export by China and Mexico Figure 19:Relevance of the manufacturing industry in US and Mexico Figure 20:Annual average real wages in China and Mexico’s manufacturing Figure 21:Wage level comparison among China and major Asian countries  The profitability of Hon Hai Precision, a Taiwan company that is the world’s biggest EMS (electronic manufacturing service) provider, is an excellent illustration of these events. Hon Hai’s after-tax profit margin was more than 10% in 2000. The margin was only 2.4% in 2011 and 2012 and fell to 2% in the second quarter of 2013. During the violent anti-Japan demonstrations that began in August 2012, there was a riot involving about 4,000 people at Hon Hai’s Chinese factory, too. The company was told that it had to raise wages by 20% every year for workers in China. Hon Hai’s business model involves using purchased technologies to manufacture goods efficiently using cheap labor and selling those products in the United States. Operations are thus based on the premise of low wages in China. But now, Hon Hai can no longer use this business model. In this environment, China will probably be unable to stop the decline in the trade surplus as well as the downturns in direct foreign investments and foreign currency reserves. Figure 22:Hon Hai Precision’s NI margin and China’s annual average earnings

The profitability of Hon Hai Precision, a Taiwan company that is the world’s biggest EMS (electronic manufacturing service) provider, is an excellent illustration of these events. Hon Hai’s after-tax profit margin was more than 10% in 2000. The margin was only 2.4% in 2011 and 2012 and fell to 2% in the second quarter of 2013. During the violent anti-Japan demonstrations that began in August 2012, there was a riot involving about 4,000 people at Hon Hai’s Chinese factory, too. The company was told that it had to raise wages by 20% every year for workers in China. Hon Hai’s business model involves using purchased technologies to manufacture goods efficiently using cheap labor and selling those products in the United States. Operations are thus based on the premise of low wages in China. But now, Hon Hai can no longer use this business model. In this environment, China will probably be unable to stop the decline in the trade surplus as well as the downturns in direct foreign investments and foreign currency reserves. Figure 22:Hon Hai Precision’s NI margin and China’s annual average earnings

Chapter 8 An Abrupt Change in Foreign Exchange Environment and the credit crunch

Since 2012 one mystery is why the Chinese Yuan still strengthening even as the country’s economic stagnation becomes more severe. The answer is probably underground fund remittances, which indicate that China is struggling with a serious credit crunch. Short-term interest rates in China spiked suddenly in the second half of June, 2013 so the country’s fund procurement difficulties came to the surface. Most people interpret higher interest rates as the result of reforms to the People’s Bank of China and measures to prevent the formation of a bubble. But this is a one-sided view. China is very unlikely to intentionally burst a bubble while economic growth is slowing. Another way to view China’s higher interest rates is that people are shunning risk worldwide because of the impending reduction in U.S. quantitative easing. But this is a contradiction, too. If investors are discounting the reduction of QE3, the dollar should strengthen as the Yuan weakens. However, the Yuan is appreciating all by itself. The reason is that money is flowing into China. Therefore, we should view the rapid upturn in short-term interest rates as the result of a shortage of funds that is greater than the People’s Bank of China expected. Figure 23:China short-term interest rate Figure 24:China Renminbi exchange spot  China’s economic difficulties can no longer be concealed. The movement of goods in China is already about to come to a halt for all practical purposes. Railroad cargo volume and electric power generation are the statistics that former Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao relies on most of all. Currently, there is almost no increase from one year earlier in either of these figures. Steel output was flat in 2012 but is now up more than 10% from one year ago. However, the purpose of this growth is probably absorbing fixed expenses rather than meeting real demand. There are reports of higher inventories of steel, which point to falling prices and cuts in steel production. China will probably have to admit that its economy will lose momentum in late 2013 and 2014. A rapid decline in economic growth will obviously bring about a shortage of funds. Revenues will immediately decrease but there will not be an immediate downturn in expenditures. Since 2012, China has somehow managed to hold foreign currency reserves steady. The country has avoided a decline in reserves despite numerous reasons for a downturn. Underground and illegal inflows of funds to China are filling in this gap. For example, on June 28, 2013, The Wall Street Journal reported that Chinese companies that have fallen into financing difficulty are procuring funds overseas and receiving those funds from overseas subsidiaries in order to remain solvent. The article stated that rapid growth is occurring in many fund procurement channels. For example, Chinese companies are going public in Hong Kong, issuing high-yield dim sum bonds (overseas Yuan-denominated bonds) and using Asian loan markets to obtain funds. Consequently, the use of overseas sources to meet fund shortages in China is probably the reason for the Yuan’s strength. Inflating prices of exports appears to be one source of inflows of funds from overseas. There have been doubts about the reliability of China’s trade statistics since 2012. Although the country reported a big increase in exports, statistics at other countries show that imports from China are flat. Many inconsistencies have occurred. Chinese authorities have reported that exporters are inflating the value of exports. China strictly controls foreign exchange. Therefore, to receive funds from another country, companies are creating fictitious export prices that exceed the actual value. Funds can then be received in the form of payments from importers. Until now, these illegal inflows were regarded as direct investments in China by foreigners. However, international investors have been holding down their investments in China. One reason is the recent drop in stock prices. Investors are also worried about non-performing loans in the shadow banking sector. Moreover, wages in coastal China are higher than in Thailand, Malaysia and all other Southeast Asian countries. Companies are moving manufacturing operations out of China. Direct investments in China started to decline in 2012 and there is no change in the structural factors behind this downturn. If this is true, then we must regard inflated export prices as inflows of funds from overseas due to the initiatives of people in China rather than investments in China from overseas. China started supervising export statistics more closely in May 2013. The result was a sharp drop in the growth of the value of exports. In other words, illegal inflows of funds were reduced. I believe we should view this as the point when China’s credit crunch quickly started to become even worse. Due to the recent surge in short-term interest rates, the severe and pervasive shortage of funds has first of all exposed the weakest link in China’s financial system: shadow banking. The shortage of funds leads to growth in non-performing loans and the insolvency of financial institutions. Due to the nature of this series of events, there can easily be an impact on the entire banking system.

China’s economic difficulties can no longer be concealed. The movement of goods in China is already about to come to a halt for all practical purposes. Railroad cargo volume and electric power generation are the statistics that former Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao relies on most of all. Currently, there is almost no increase from one year earlier in either of these figures. Steel output was flat in 2012 but is now up more than 10% from one year ago. However, the purpose of this growth is probably absorbing fixed expenses rather than meeting real demand. There are reports of higher inventories of steel, which point to falling prices and cuts in steel production. China will probably have to admit that its economy will lose momentum in late 2013 and 2014. A rapid decline in economic growth will obviously bring about a shortage of funds. Revenues will immediately decrease but there will not be an immediate downturn in expenditures. Since 2012, China has somehow managed to hold foreign currency reserves steady. The country has avoided a decline in reserves despite numerous reasons for a downturn. Underground and illegal inflows of funds to China are filling in this gap. For example, on June 28, 2013, The Wall Street Journal reported that Chinese companies that have fallen into financing difficulty are procuring funds overseas and receiving those funds from overseas subsidiaries in order to remain solvent. The article stated that rapid growth is occurring in many fund procurement channels. For example, Chinese companies are going public in Hong Kong, issuing high-yield dim sum bonds (overseas Yuan-denominated bonds) and using Asian loan markets to obtain funds. Consequently, the use of overseas sources to meet fund shortages in China is probably the reason for the Yuan’s strength. Inflating prices of exports appears to be one source of inflows of funds from overseas. There have been doubts about the reliability of China’s trade statistics since 2012. Although the country reported a big increase in exports, statistics at other countries show that imports from China are flat. Many inconsistencies have occurred. Chinese authorities have reported that exporters are inflating the value of exports. China strictly controls foreign exchange. Therefore, to receive funds from another country, companies are creating fictitious export prices that exceed the actual value. Funds can then be received in the form of payments from importers. Until now, these illegal inflows were regarded as direct investments in China by foreigners. However, international investors have been holding down their investments in China. One reason is the recent drop in stock prices. Investors are also worried about non-performing loans in the shadow banking sector. Moreover, wages in coastal China are higher than in Thailand, Malaysia and all other Southeast Asian countries. Companies are moving manufacturing operations out of China. Direct investments in China started to decline in 2012 and there is no change in the structural factors behind this downturn. If this is true, then we must regard inflated export prices as inflows of funds from overseas due to the initiatives of people in China rather than investments in China from overseas. China started supervising export statistics more closely in May 2013. The result was a sharp drop in the growth of the value of exports. In other words, illegal inflows of funds were reduced. I believe we should view this as the point when China’s credit crunch quickly started to become even worse. Due to the recent surge in short-term interest rates, the severe and pervasive shortage of funds has first of all exposed the weakest link in China’s financial system: shadow banking. The shortage of funds leads to growth in non-performing loans and the insolvency of financial institutions. Due to the nature of this series of events, there can easily be an impact on the entire banking system.

Chapter 9 Slowing economic growth may create a crisis for China’s communist dictatorship system

The events I have just explained show the severity of the tight-money situation in China. A rapid slowdown of economic growth is one problem. But China also has a structure that makes the emergence of a fund shortage inevitable. The shortage is not the result of government reforms; the real cause is that money is no longer circulating in China. By building up massive foreign currency reserves, China was able to continue to make unprecedented and even wasteful investments. The result was a prolonged period of economic growth. Investments have surpassed consumption every year since 2003. Capital formation rose to the abnormally high level of 46% of GDP in 2011. But the obstacles created by these excessive investments are finally emerging all at once. Real estate investments, corporate capital expenditures and public-works investments were all made in accordance with the desires of the Communist Party rather than for rational economic reasons. Most of these expenditures will probably end up as non-performing investments. As these investments were made, only companies and governments accumulated wealth. Labor’s share of income in China is extremely low and buying power is not increasing outside China’s large cities. Apparently, the Chinese economy has at last reached structural dead end. Major components of the Chinese economy will probably suffer from a decline in earnings. Falling earnings will expose the real situation at government-owned companies that have relied on subsidies under the Communist Party regime. The financial condition of companies that have consistently used suspicious and fraudulent accounting practices will also be exposed. The result is likely to be enormous non-performing assets consisting of loans to these companies along with a steady stream of huge bankruptcies. Investment-fueled growth that was nothing more than a papier mâché tiger is over. China can no longer sustain its enormous volume of investments. In the past, investments fueled more than half of economic growth. But from now on there will be no contribution from investments or even a negative effect. Declines in jobs and wages will be unavoidable and consumption will drop, too. The Chinese economy is very likely to fall to no growth. These events will reveal the problems with the Chinese economy and China’s socialist market economy, which is an illogical term. All these events will probably deepen the crisis faced by China’s communist dictatorship government. The reason is that no one in China believes in “carrying out the communist revolution.” Positioning a communist dictatorship as an essential system for achieving economic growth was the only way to justify the existence of this system. Once growth stops, the system will face a crisis. The end of economic growth will therefore immediately take away the legitimacy of Communist Party dictatorship system.